Opinion Focus

- Variety could make Brazil one of the world´s largest wheat exporters.

- Production already started in the Midwest with good results.

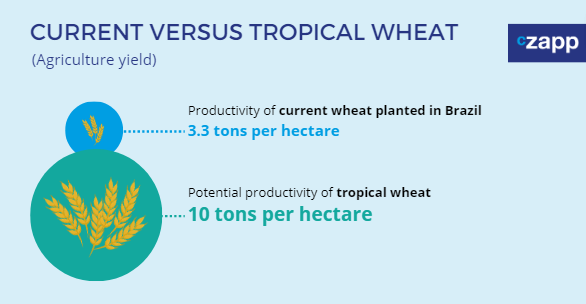

- Tropical wheat yield is 3 times higher than that of common wheat.

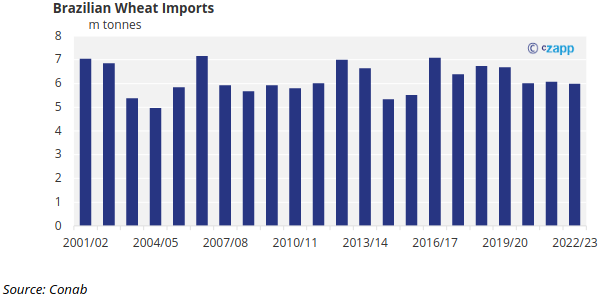

After 40 years of research, Brazilian scientists and agronomists managed to develop wheat varieties that can be grown in hot and dry areas, typical of the tropical climate. Production has already started in the cerrado, in states such as Goiás and Minas Gerais, with good results. The expectation is to make Brazil self-sufficient in the production of wheat, the only agricultural commodity that the country needs to import.

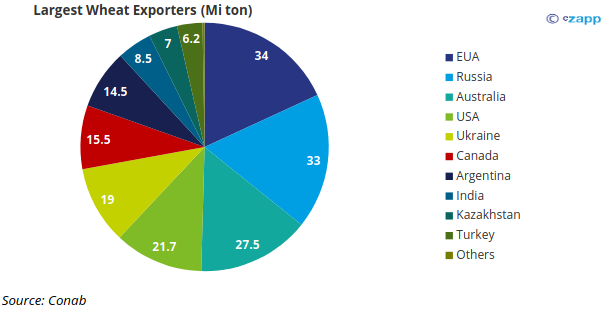

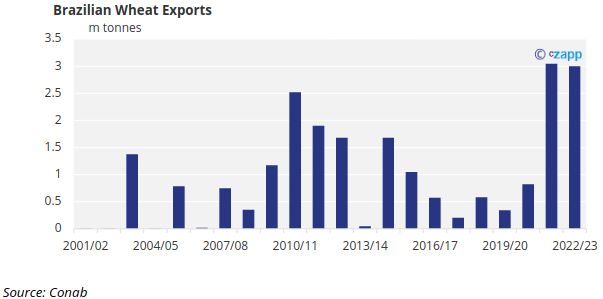

The country has even greater ambitions. In ten years, if all goes well, Brazil will be able to compete for a place among the world’s largest exporters of the cereal, alongside the European Union (responsible for around 17% of global shipments), Russia (16.4%) and Australia ( 13.7%).

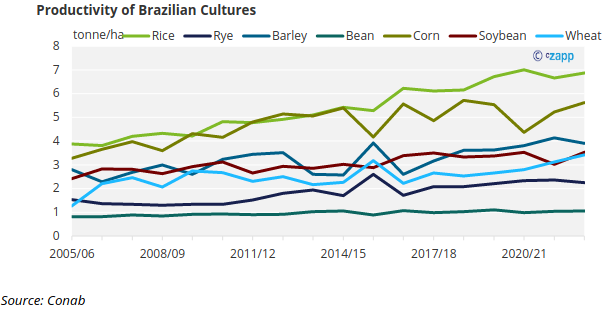

Today, the Midwest, where tropical wheat has been cultivated, is responsible for 10% of the national cereal production (the rest comes from the South region). The country already has a productivity champion. It is rural producer Paulo Bonato, from Cristalina, in Goiás, who harvested 9.63 tons of wheat per hectare, three times more than last year’s national average.

“The genetic potential of the seed we plant in the cerrado can reach a productivity of up to 10 tons per hectare”, says Celso Moretti, president of Embrapa (Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation), in an exclusive interview with Czapp.

Embrapa, created in 1973, is responsible for research and field tests on tropical wheat, the result of studies on genetic improvement. In recent decades, the institution has developed several agricultural varieties that have reduced the country’s dependence on food imports and helped to place Brazilian agriculture on the world map of exports.

Brazil has always been a wheat importer, but this reality could change, right? How is research on tropical wheat progressing?

Yes, historically Brazil has always been a major importer of wheat. It is the only commodity that Brazil imports. It is estimated that this year Brazil will need something around 13 or 14 million tons of wheat. In the 2021/2022 crop, we managed to produce almost 10 million tons of wheat. In 2019, we produced 6.2 million tons.

In three years, we went from around 6.2 million tons to almost 10 million tons. What is this due to? Basically, we had an increase in the production area. We went from 2.8 million hectares to 3.1 million hectares, 90% of which is in the south of Brazil, with a temperate weather. But the cerrado, in Goiás and Minas Gerais, is already starting to emerge with around 10% of this area with the production of tropical wheat.

How did tropical wheat develop?

For 40 years, we have been investing in the genetic improvement of wheat. Since 2010, we started to test the adaptation of wheat to the tropical climate. Embrapa started to bring types of wheat from other regions of the world, adapted to high temperatures and less water availability, and to cross them with the material we have here in Brazil. We started to take this tropical wheat to Minas Gerais, Goiás and the surroundings of the Federal District.

These types of wheat adapted to the dry and hot climate came from which countries?

There were several countries. We brought a lot of material from Mexico, as well as Argentina, Europe, the United States. Wheat originates from a region known as the Great Crescent, in the Middle East, in countries that are now Iran, Iraq, Syria. It is a very important food for world food security. Anyone who remembers the Arab Spring and the revolution that took place in Egypt knows that the demonstrators asked for three things, justice, freedom and bread. But the bread was not in the figurative sense of food, they really wanted bread.

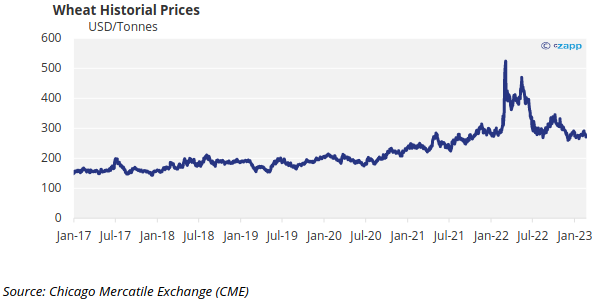

And now, the war in Ukraine represents one of the reasons why wheat production in Brazil has increased. Ukraine is a big producer of wheat. To give you an idea, 70% of the wheat that Egypt imported came from Ukraine. Several countries began to look for other sources of supply and one of them was Brazil.

As prices on the international market rose, growing wheat became interesting. And this wheat crop is going to the Midwest because Embrapa has developed tropical wheats, which are BRS 264, BRS 254 and BRS 404.

And there are other important points. First, this wheat is of very high quality. It has a protein content of 15%, which is quite high. Wheat averages 7% or 7.5% protein. The higher the protein content, the more wheat adapts to baking.

And in what months is tropical wheat planted?

In the cerrado, wheat is planted from March to June. Soybeans and corn are the main crops from October to February. So, tropical wheat represents an extra source of income for the farmer.

Is this wheat considered a hard grain?

Yes. It is an excellent wheat to produce bread and pasta. The wheat in the cerrado is of the durum grain type. This is the first point. The second is that Embrapa mapped the cerrado, which is the second largest biome in Brazil, behind only the Amazon biome. We have 4 million hectares in the cerrado already in consolidated areas, that is, areas that do not need to be deforested, capable of adapting to tropical wheat.

And is there interest from rural producers in using this area to grow wheat?

I have no doubt. But it needs to have a good price in the market. The producer also needs credit and the mills that are closest to the Midwest.

The mills are closer to the coast, aren’t they? Is this a challenge?

There is no point in taking wheat production to the Midwest if the mills continue on the coast or in the south of the country. In Fortaleza, there is a huge wheat mill. And why is it there, on the coast? Because Brazil imports wheat. it already arrives by ship, at the ports. It’s a question of logistics. I’m always asked what it takes to make this work. Well, Embrapa has already done its part, of developing the technology. Now, we need resources for entrepreneurs to scale the mills and, obviously, prices on the international market.

Brazilian robot monitors soy and cotton autonomously

Brazilian robot monitors soy and cotton autonomously

How do you see the issue of granting credit and investments?

For the entrepreneur to make an investment of this size, he needs to be certain that he will be able to have a payback in a reasonable time. It needs a project of economic viability. It cannot be to process wheat from a single harvest, it needs to have a forecast for more harvests. So it’s not a very simple thing.

For the export is a little less complex?

This is an interesting point. You see that last year Brazil produced almost 10 million tons and exported 3 million. We do have the possibility of exporting more and more. I have been saying that if international market conditions remain as they are today, with wheat prices on the rise and Ukraine having difficulty producing and selling them, I imagine that the world market will continue to be heated.

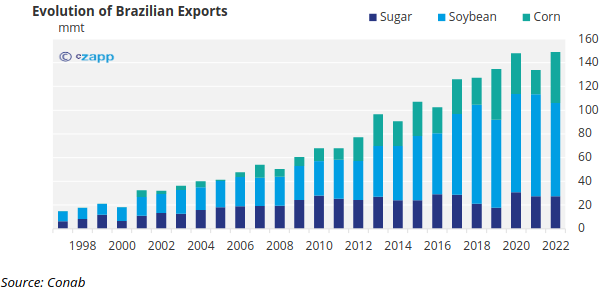

Brazilian producers will produce more. In less than five years, Brazil should become self-sufficient in wheat production. And then the idea is that what happened to soybeans and corn will happen to wheat. Wheat should start making this journey towards the center of Brazil. With this, Brazil could become a major wheat exporter, which should happen within ten years. There should also be an increase in productivity.

How should this productivity growth happen?

We will occupy areas that are already consolidated. I always stress this. We are not talking about deforesting. These are areas already used for agriculture. And we will also have a vertical increase in productivity. The average productivity in Brazil is around 3.3 tons per hectare.

But the genetic potential of the seed that we planted in the cerrado can reach up to 10 tons per hectare. There is even a producer who harvested almost ten tons per hectare. It’s Paulo Bonato, who harvested up to 9.6 tons per hectare. This is what we talk about genetic potential. We are optimizing the technology and we see how much increase in productivity we can reach.

Has Embrapa been conducting research in this sense, to increase wheat productivity?

Yes. Not just for wheat, but for other crops as well.

Sugar and ESG

Sugar cane is one of those crops, isn’t it?

We have a sugarcane improvement program that works to increase productivity and disease resistance. Recent work was carried out with two varieties of sugarcane, flex 1 and flex 2.

One variety we developed is to have a higher sucrose content and the other has a softer cell wall and is therefore easier to digest. This facilitates the construction of biomass. This technology opens up a world of possibility.

This type of research could even be interesting to make plants more resistant to climate change, right?

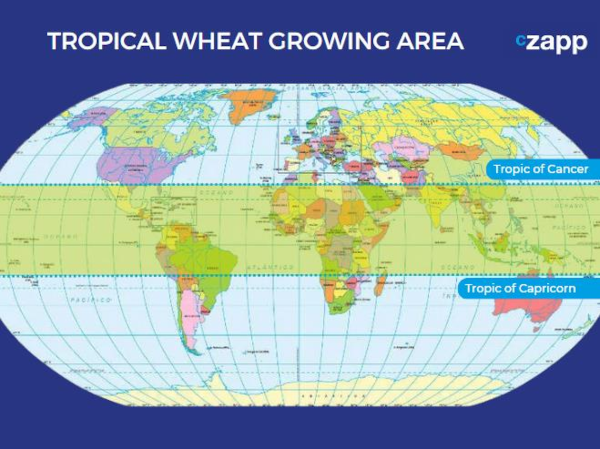

Exactly. Imagine the importance that wheat has in agriculture and world food security. Wheat accounts for 20% of all calories that humans consume. In the tropical belt, the Tropic of Capricorn area, which passes through São Paulo, and the Tropic of Cancer, tropical wheat can be cultivated. It can even be cultivated in regions of Africa that have a great water restriction. It really is something that opens up a lot of opportunities.

About ESG in agriculture, does Embrapa have new projects?

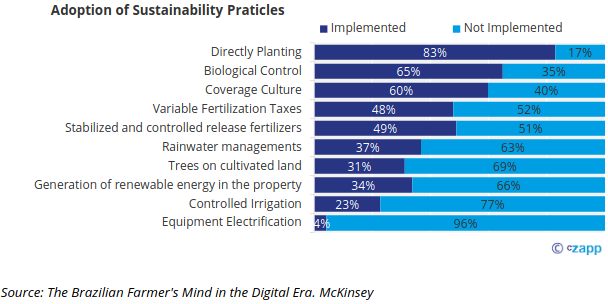

ESG is very interesting because it has become a reality in companies. One of the ESG fronts at Embrapa is the bioinputs part. The most emblematic case is rhizobium, a bacterium that fixes nitrogen from the atmosphere for soybean. We also have the bacteria that mobilize the phosphorus that is in the soil. This market will grow double digits over the next five years.

By 2025, Brazil will be the largest or second largest producer of bioinputs in the world. There are two fronts, biofertilizers, which are microorganisms that help reduce the need for fertilizers or mobilize fertilizer, and there is the part of biopesticides. This makes it possible to reduce the consumption of chemical pesticides.

Embrapa has been investing heavily in partnership with the private sector, bioinputs and biopesticides. In 2021, we launched a bioinsecticide to control the main corn pest, which is the Carthusian armyworm. There is a very clear demand for sustainable food production, and this involves using technology linked to the development of bioinputs.