It looks at the science behind hunting quotas, the pressures affecting elephant numbers and how the government decides how many elephants can be taken. Because Botswana has the world’s largest remaining savannah elephant population, weak management can affect conservation, rural communities and wider international wildlife policy.

The report, authored by Scott Schlossberg and Michael Chase, focuses on the sustainability of current hunting levels. It does not advocate for or against trophy hunting; instead, it evaluates the quality of the science used by the Department of Wildlife and National Parks (DWNP) and explores how hunting interacts with poaching, drought, tusk breakage and elephant movement. These combined pressures help show whether trophy hunting can continue without harming the long-term health of Botswana’s elephants.

Understanding elephant age structure

Elephants can live for more than 60 years and reproduce slowly. Mature bulls, in particular, are biologically and socially significant. Bulls in their 30s and older play key roles in guiding younger males, maintaining social order and contributing the majority of successful breeding. However, they naturally make up only a small proportion of any wild elephant population.

The report explains that even in well-protected populations, large, old bulls are rare. For example, in Tanzania’s Tarangire ecosystem, where elephants face minimal poaching or hunting, males aged 25 to 39 comprise only about 5% of the population. Males aged 40 or older make up less than 1%. When hunting targets the biggest bulls, it reduces an already limited segment of the population.

EWB’s modelling shows the impact clearly. With the current quota of about 0.3% of the total population per year, bulls aged 30 and older could drop by almost 25% compared with a no-hunting situation. Bulls over 50 could fall by 50%. These losses matter because hunting relies on large males, and elephant society relies on their leadership and breeding role.

Quotas and biological realities

DWNP says that hunting up to 1% of the national elephant population each year is sustainable. The report finds no scientific support for this claim and shows that different quota levels lead to very different results.

When the quota is set at 1%, large bulls disappear rapidly from the population. At the current level of 0.3%, mature males still decline substantially, especially when combined with other pressures. According to the report, more sustainable outcomes are observed at lower quotas between 0.1 and 0.2%. These would maintain a greater number of older bulls and allow the population to absorb periods of heightened ecological stress.

A key problem is how DWNP decides which elephants are counted as available for hunting. The department assumes that elephants move freely between hunting and non-hunting areas, forming a single well-mixed population. The report argues that this assumption does not reflect reality. Elephants in heavily hunted concessions rely on animals immigrating from neighbouring protected areas. If movements are disrupted by drought, fences, or human disturbance, the hunted population may not replenish itself.

What the new models show

To assess whether hunting is sustainable, the authors built a new model using real survival data, male and female differences and the selective removal of big bulls. This is different from the older Craig et al. model still used by DWNP, which relies on invented numbers and assumes elephants always breed at full speed. The report says these flaws weaken the scientific basis of today’s quotas and the Non-Detriment Findings submitted to CITES.

EWB’s modelling shows that ecological stressors make each other worse. Droughts, poaching and movements restricted by fences all reduce the number of big bulls.

When combined with hunting, these pressures produce declines in both the number and the average tusk size of hunted elephants. Under a 0.3% quota, trophy size declines when ecological pressures interact. Under a 0.1% quota, the system is more resilient, and the decline in trophy size is more modest.

“In our models, we predicted what will happen to the hunting industry under different scenarios for the future,” says report author Scott Schlossberg. “When numbers of bulls become depleted, this directly impacts the hunting industry: they have fewer bulls to hunt, and hunters are forced to take younger bulls with smaller tusks. That sort of change can impact the hunting outfits’ bottom line and the revenue that Botswana receives from hunting fees. A sustainable hunting industry requires a healthy elephant population.”

Interactions with poaching, drought, tusk damage and human-wildlife conflict

Hunting does not operate in isolation. The report emphasises that Botswana faces several external pressures that can reduce the pool of huntable elephants.

Poaching is still a concern. Even relatively small numbers of illegally killed bulls can reduce trophy quality and also the availability of older males. The report notes the importance of improved monitoring and surveillance. Appendix 2 of the report shows that poaching is rising in important northern landscapes and that poachers are targeting the same large, older bulls valued by trophy hunters. Even low levels of poaching can shrink the number of mature bulls, disrupt social behaviour and reduce trophy quality. The report calls for stronger surveillance, faster reporting of carcasses and open records of elephant deaths.

The report warns that this organised, cross-border poaching is now one of the most serious threats to Botswana’s elephants. During 2017–2018, 156 poached carcasses were recorded, suggesting around 400 elephants were killed in five hotspots. Between October 2023 and May 2025, a further 120 elephants were poached in NG15 and NG18. Over six months, authorities intercepted seven armed gangs leaving Botswana with freshly taken tusks, confiscating 103 tusks weighing nearly three tonnes.

Using a conservative value of USD 1.5 million per elephant, the poaching of around 120 elephants a year equals about USD 180 million (BWP 2.51 billion) in national losses. This is wealth taken directly from the State, from rural communities that rely on wildlife income, and from the tourism sector.

“In Botswana, poachers and trophy hunters are both targeting the same elephants: older bulls with big tusks,” says Schlossberg. “Poaching directly affects hunting by reducing the number of bulls available to hunters. In the long run, controlling poaching is one of the best ways to ensure the sustainability of legal hunting.”

Drought also complicates management. Climate projections suggest more frequent drought events in southern Africa. Drought kills more elephants (especially reducing numbers of calves and females – leading to lower numbers of bulls in future years).

Retaliatory killings linked to rising conflict in agricultural zones cause additional losses. When these pressures overlap, the effects get worse. Drought-weakened bulls are easier targets for poachers, conflict kills more males, and the shortage leaves hunters focusing on the last old bulls.

Tusk breakage is another issue. Many big bulls damage their tusks during fights or when pushing over trees. These bulls are still important to the population but are less attractive to hunters. This reduces the number of huntable elephants, yet DWNP does not include tusk damage in its quota calculations.

The report discusses disease as one of several additional mortality risks that could influence elephant numbers and, therefore, the sustainability of hunting quotas.

The report notes that a major disease event occurred in 2020, when approximately 350 elephants died in northern Botswana, most likely from bacterial septicaemia. It also highlights that seasonal pans in the region harbour viruses potentially lethal to elephants. Although mass disease die-offs are described as historically uncommon, the report warns that future outbreaks could affect population size and age structure, and should therefore be incorporated into hunting planning if they continue or increase.

Together, these threats demonstrate that Botswana’s elephant population, though large, contains a narrow and irreplaceable pool of prime-aged males that could be depleted if hunting is combined with these additional threats.

“When DWNP was planning for hunting, they assumed a healthy environment with few threats to elephants,” says Schlossberg. “In the real world, we know that elephants are being lost to drought, poaching, disease, and retaliatory killings. We don’t know exactly what future levels of these losses will be. Setting a lower quota, at 0.1 or 0.2% of the population, is the best way to ensure that we have enough mature bulls to withstand whatever happens in the future

Hunting in photographic tourism zones

The report raises concerns about hunting inside areas designated for photographic tourism. One example is NG13, a section of an elephant movement corridor connecting the Okavango Delta to Angola. NG13 is a photographic tourism zone, yet it remains the only part of this transboundary corridor where hunting is still permitted. The authors argue that this undermines the corridor’s ecological integrity and disregards the intended land-use designations. It also risks conflict between hunting operators and photographic tourism, both of which depend on the presence of large bulls.

Controversial finding: Quotas exceed DWNP’s own stated maximum

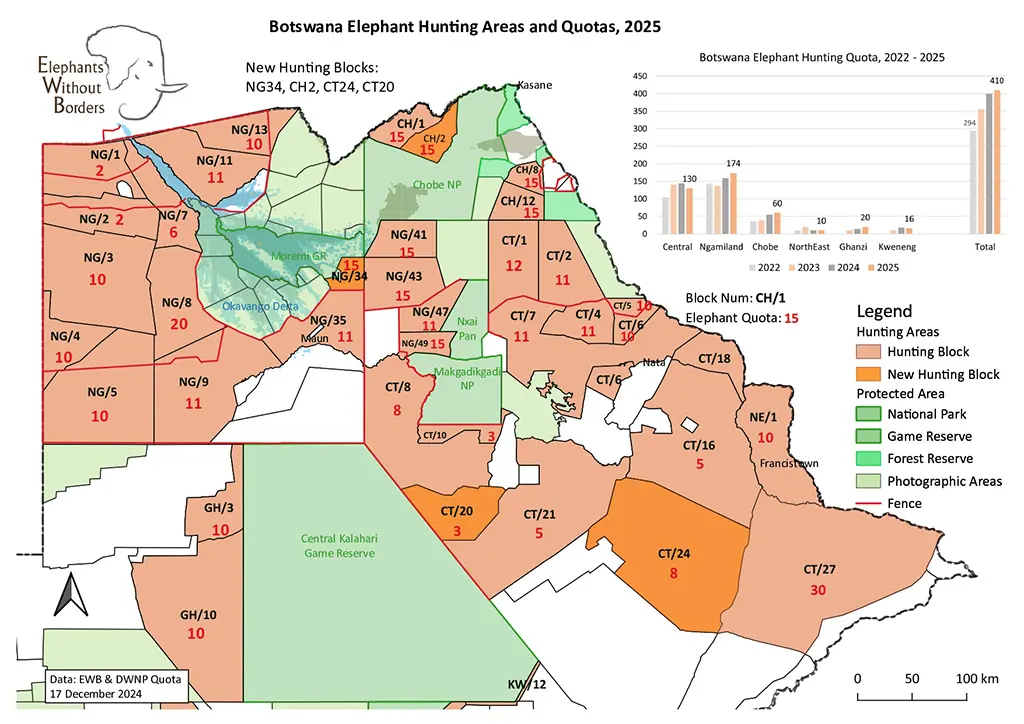

One major finding is that DWNP is not following its own quota formula. DWNP’s own Non-Detriment Finding says hunting should stay below 0.5% of the elephants inside hunting blocks. These blocks contain about 45,000 elephants, which means the quota should be around 225 elephants.

However, the report shows that the 2025 quota was set at 410 elephants and later raised to 431. This equals about 0.9% of the elephants in the hunting blocks, which is almost double the limit DWNP itself set. The authors say this large difference weakens the scientific credibility of the quota system and increases the risk of overharvesting mature males. Supporters of the current system may argue that quotas are based on the national elephant population instead. The report explains that this approach conflicts with DWNP’s own written guidance for how quotas should be calculated.

Controversial finding: Limited transparency and potential conflicts of interest

The report says a lack of transparency is a significant problem in the hunting programme. EWB documents four years of unanswered requests to DWNP and the Ministry of Environment for basic hunting data. Data such as ages and tusk measurements of hunted elephants, annual offtakes, quota allocations per concession and records of elephants killed through Problem Animal Control were requested. None of this information has been provided.

“If elephant hunting in Botswana is sustainable, then there should be nothing damaging or embarrassing in the data preventing its being shared with the public. Releasing this data could increase public confidence that elephant hunting in Botswana is sustainable,” state the authors.

The report also notes concern over the conflict of interest arising from a pro-hunting organisation (Conservation Force) authoring national management plans with limited public consultation.

The authors say that without public access to these records, it is impossible to judge whether hunting is truly sustainable. They point out that Conservation Force, a US-based hunting advocacy organisation, prepared Botswana’s Elephant Management Plan. According to the report, this process involved minimal public consultation, raising questions about conflicts of interest and whether national wildlife policy is being shaped without adequate scientific review.

Supporters of the current system may argue that hunting contributes to community livelihoods and that opposition risks undermining Botswana’s sovereign right to manage its wildlife. The report, however, frames transparency as a strength rather than a threat, arguing that robust data sharing would enhance public trust and improve decision-making.

Recommendations and the way forward

The authors recommend several changes to make the hunting programme more sustainable. They suggest reducing maximum quotas to 0.2% of the elephant population, improving transparency by releasing hunting and Problem Animal Control data each year, and honouring photographic tourism zones within Wildlife Management Areas.

The report also recommends restricting hunting to the dry season, when elephants are more predictable and less widely dispersed, and increasing anti-poaching efforts through aerial surveillance and technology.

The main message is that sustainable hunting requires careful management, realistic scientific assumptions, and open decision-making. Selective hunting combined with drought, poaching and other pressures creates risks that can only be reduced through strong science and transparent oversight.

Why this matters

Botswana’s decisions will influence African savannah elephants across southern Africa. The country hosts more than a third of the continent’s remaining elephants, and its landscapes form vital movement corridors for transboundary wildlife populations. The hunting programme, therefore, has implications well beyond individual concessions.

The report shows that hunting must be managed alongside ecological, economic and social needs. Whether people support or reject trophy hunting, the future of Botswana’s elephants depends on quotas based on solid evidence, open decision-making and monitoring systems that track the combined effects of multiple pressures. As climate change intensifies and land use becomes more contested, clear, transparent and science-based management is essential to protect both elephants and the livelihoods that depend on them.