The aspect of climate change I’m most concerned about is its impacts on agriculture and food security

. This is a risk that we can (at least partially) address by developing temperature- and drought-resistant crops, and by making sure that farmers – especially the poorest – have access to basic technologies like irrigation, the best seed varieties, fertilizers, and pesticides. I don’t think the world is investing enough in future-proofing food production, so it’s a problem I think about a lot.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) tracks agricultural conditions worldwide and frequently updates its outlook on global production for the year. I check this pretty often to see how things are looking.

Temperatures over the past year have been very high, so people are rightly concerned about how crop production is holding up.

This post gives a quick summary of what the USDA is projecting for the year based on its latest update. I’m focusing on the main cereal crops, plus soybean, which make up the majority of the world’s calories. Some of the other crops that I wanted to include: like potatoes, or leafy greens, aren’t included in the USDA’s database.

As I’ll repeat many times in this article: these are projections based on the latest assessment of growing conditions and planting areas. This could change in the next five months for various reasons, so should be taken with caution. I’ll give another update towards the end of the year to see how these USDA projections hold up.

Global production of key staple crops

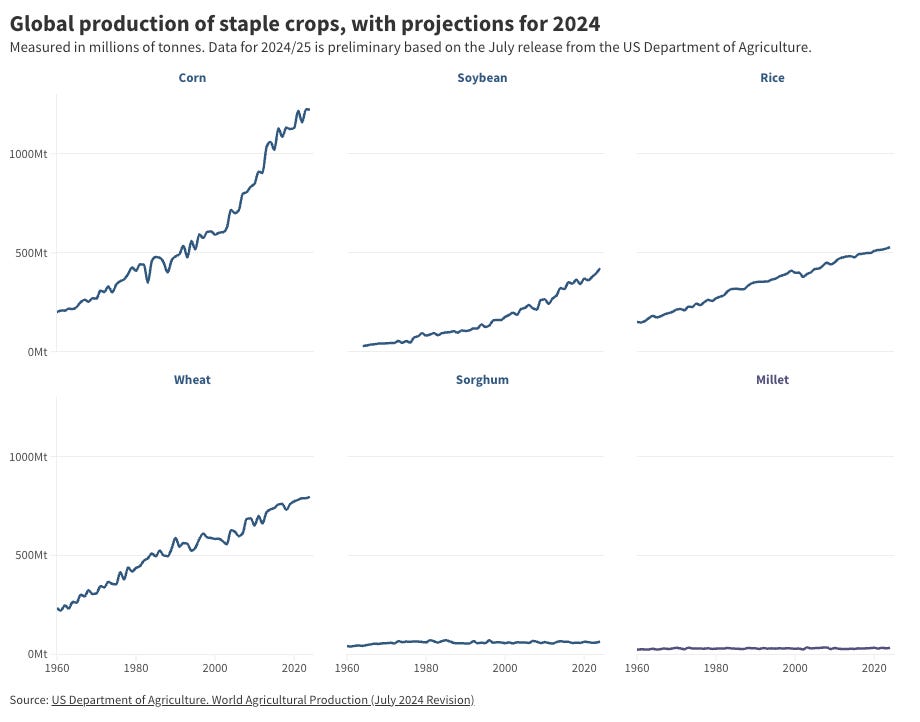

The chart below shows the global production of cereal crops and soybeans, from 1960 onwards. The figure for 2024 is the latest USDA projection.

You can see that the production of corn, soybean, rice and wheat in particular has seen a relatively steady increase for decades.

Projections for this year are on course for record highs.

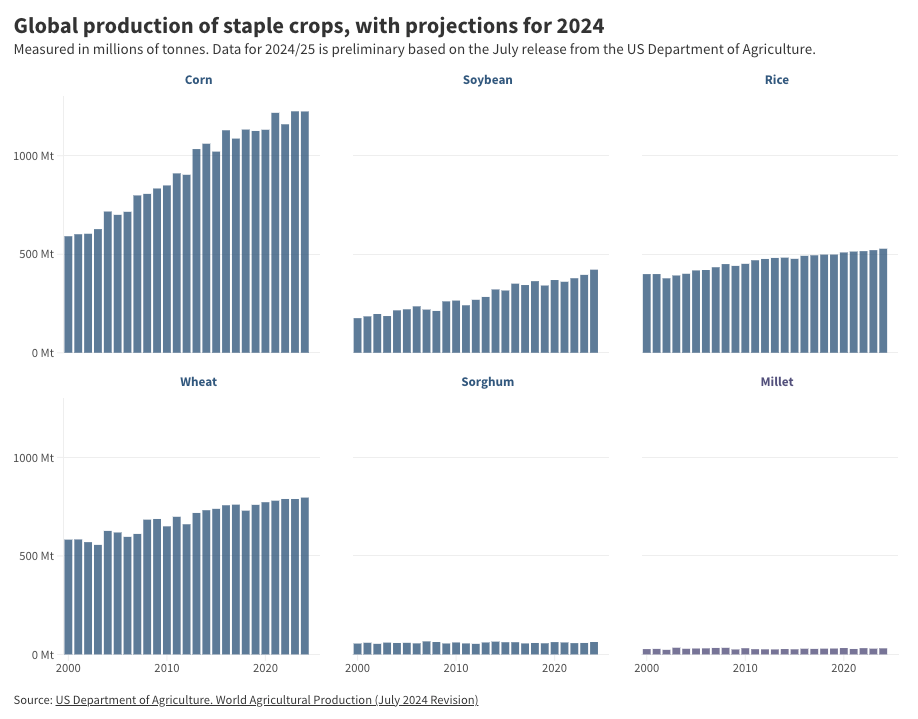

To see this clearer, let’s zoom in on production figures since 2000. This is in the chart below.

Again, despite year-to-year variability, there has been a gradual increase over the last few decades. The USDA projects that corn production is on track to replicate last year’s record high. Soybean, rice, and wheat are all projected to slightly beat production in previous years.

Yields of key staple crops are holding strong

There are two ways to increase crop production: use more cropland, or achieve higher yields. For environmental reasons – to prevent huge expansions of agriculture into forests and natural habitats – we want to achieve higher yields. This is better for farmers too, as they get higher returns.

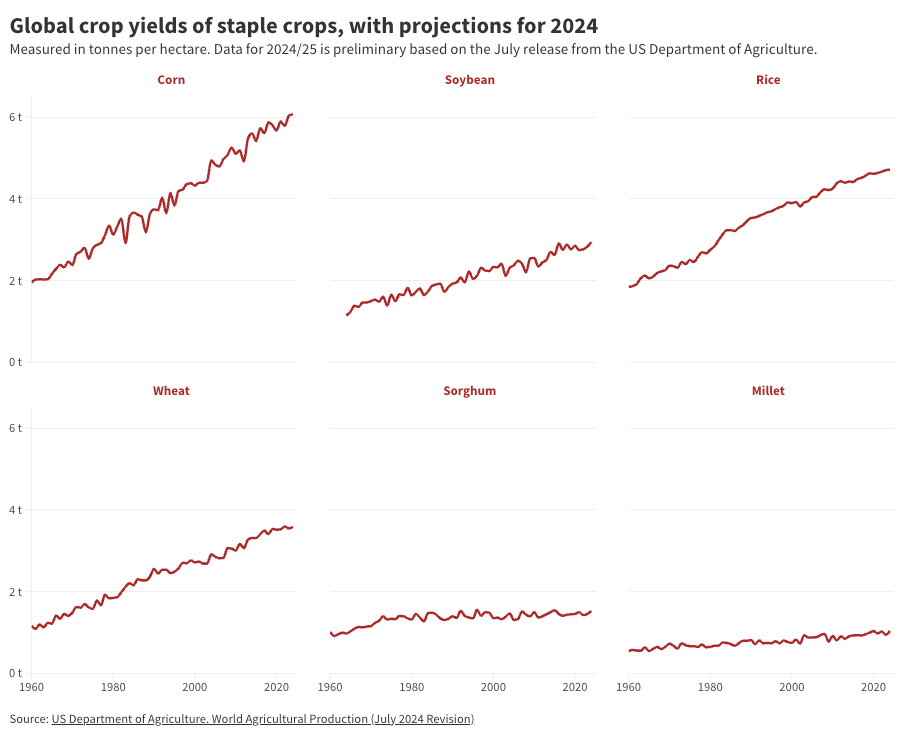

The good news is that crop yields are still on the up. You can see this trend since 1960 in the chart below.

The first thing to note is how low sorghum and millet yields are compared to corn and rice. These are key crops across Sub-Saharan Africa, but unfortunately, haven’t had the same development and investment as other cereal crops. I’ve written many times previously about the need for more attention on agricultural productivity – particularly for African countries – not only for climate resilience, but to reduce poverty and improve regional food security.

The second point is that all other cereal crops are projected to see very high yields. Corn, soybean, and rice are projected for all-time highs. Wheat is projected to be in just below the 2022 record.

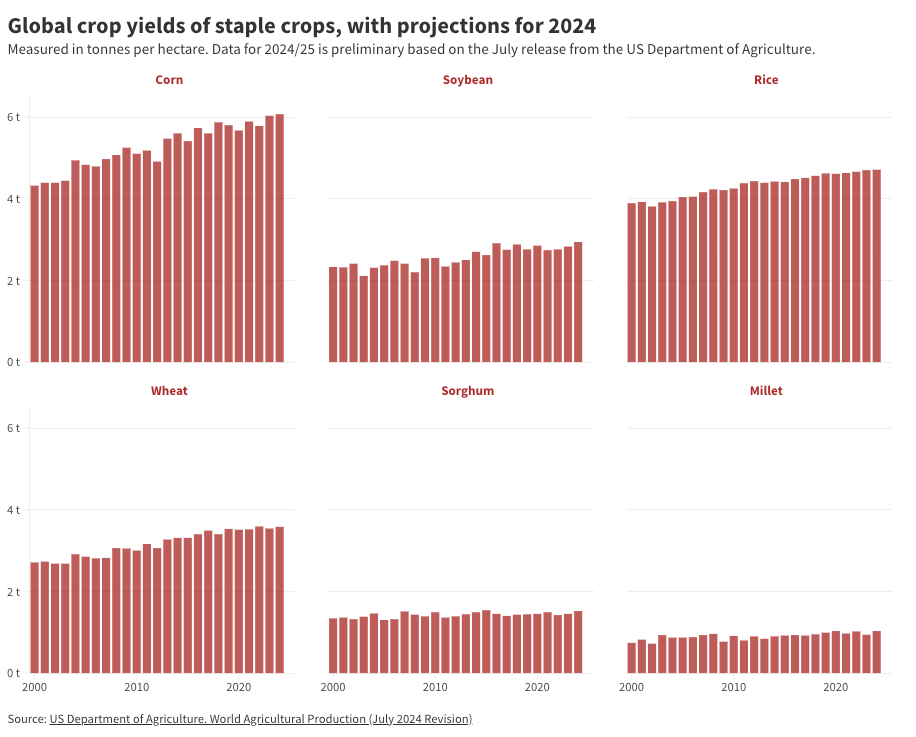

The chart below shows this more clearly over the last few decades since 2000. Again: these are projections and are therefore uncertain. But even if these drop by the end of the year – and lose out on record highs – they are unlikely to be far below yields seen in previous years.

Food prices beginning to stabilise, says Competition Commission

Food prices beginning to stabilise, says Competition Commission

How reliable are USDA projections?

I’ve cautioned multiple times that these are projections that come with uncertainty. But how much?

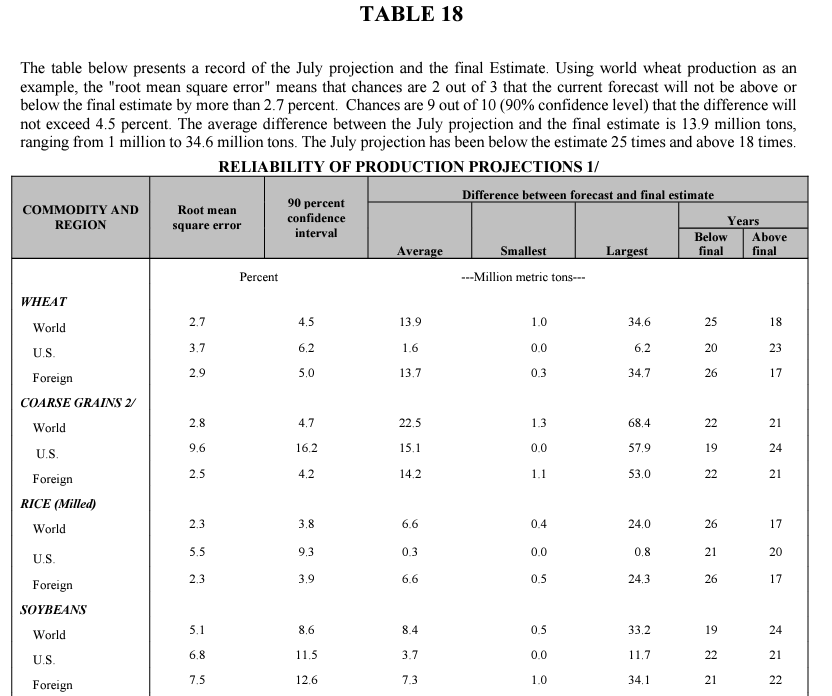

The USDA does publish data on how reliable its production projections have been in the previous 43 years. You can see its estimates in the table below.

It varies quite a bit by crop. For wheat, for example, the July estimate has been more likely to underestimate the final estimate than overestimate. For soybeans, it’s the opposite.

Let’s take the example of wheat and see how the reliability would affect the charts above. The USDA projects that global wheat production will beat the previous record (last year) by 8 million tonnes. From the table below we can see that the average difference between the forecast and the final estimate is 13.9 million tonnes. This “record” is well within the bounds of uncertainty.

The largest difference between the forecast and the final estimate for wheat was 34 million tonnes. If the 2024 projection was off by this much, production would drop to 762 million tonnes. This is lower than the previous years, but higher than 2019 and all of the years before that.

Rice is projected to beat last year’s record by 8 million tonnes. The average difference between the projection and the final estimate is 6.6 million tonnes. So, it’s within that range. But if it was to see the maximum uncertainty – 24 million tonnes – it would also fall back to production levels in 2019.

A varied picture of production across the world

Of course, this doesn’t mean this is going to be a good farming year everywhere (or for every crop).

A few months ago, I did a deep dive into the cocoa crisis across West Africa. Production has been way down as a result of El Niño plus climate change, outbreaks of Black Pod disease, and the Swollen Shoot virus, combined with chronic underinvestment.

The USDA also provides more in-depth coverage of countries or regions where production is up and where it’s down on previous years.

Cotton production in Pakistan is projected to fall, but rice production is expected to see a record. Indian wheat production and yields are also on-track for a record. Corn production in Europe and cereal production in Russia are expected to be down. Mexico is projected to see the lowest corn production in two decades because of drought.

There can be large disruptions in national or regional production without major changes to global production.

An interconnected, globalised food system has its downsides. But its major upside is that deficits in some places can be balanced out with surpluses elsewhere. In the past – when all you had was local produce – a bad harvest meant hunger. Today, that’s not necessarily the case thanks to global trade (although it still has severe socioeconomic impacts on farmers).

Based on these early projections, the global agricultural system is proving resilient. Of course, this could change in the next five months. Towards the end of the year, I’ll revisit these numbers to see whether the USDA’s projections hold.