Erwin Schrodinger (1945) has described life as a system in steady-state thermodynamic disequilibrium that maintains its constant distance from equilibrium (death) by feeding on low entropy from its environment—that is, by exchanging high-entropy outputs for low-entropy inputs. The same statement would hold verbatim as a physical description of our economic process. A corollary of this statement is that an organism cannot live in a medium of its own waste products.

It governs key physical properties like moisture, temperature, and structure, primarily driven by thermal conductivity () and heat capacity. Soil moisture, texture, and organic matter significantly influence heat flow, with moist, dense soils conducting heat better than dry, loose soils.

At its most basic thermodynamic level, agriculture is an energy harvesting industry. Its purpose is to capture Exergy from the sun (via photosynthesis) and package it into a form humans can consume (calories).

However, over the last century, we have fundamentally broken this equation. We have stopped relying on the "Flow" of sunlight and started relying on the "Stock" of fossil fuels.

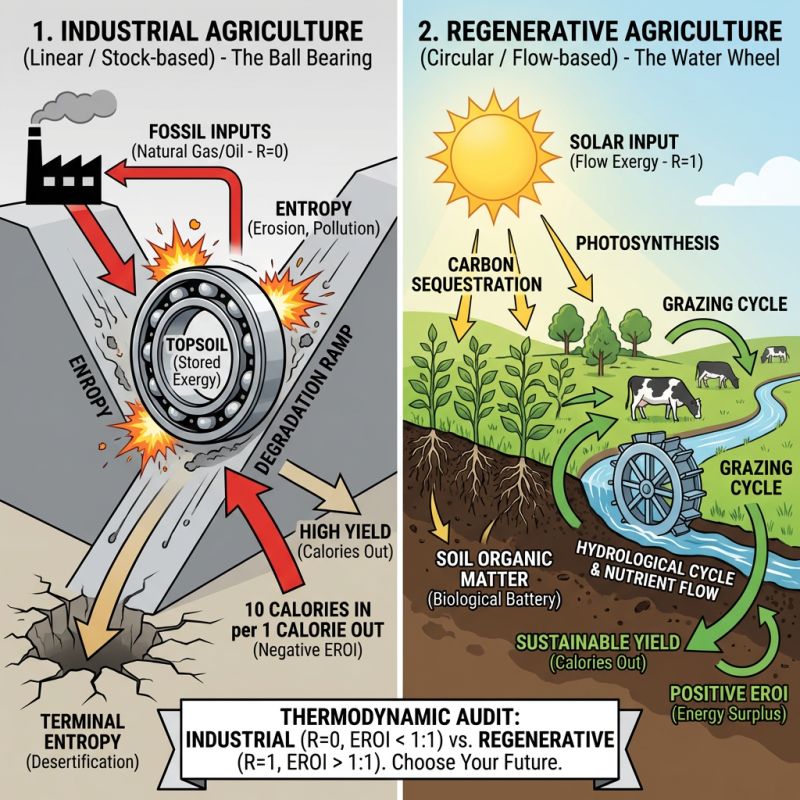

With modern farming through the lens of Thermodynamic Viability, two distinct physical models:

Industrial Agriculture: A linear machine that converts petroleum into food The Ball Bearing.

Regenerative Agriculture: A biological cycle that captures solar flow to build storage (The Water Wheel).

The Industrial Model: Eating Oil (The Linear Approach)

Industrial agriculture is often praised for its "Efficiency" yield per acre.

It looks efficient only because we ignore the energy inputs required to sustain it.

The Thermodynamic Cheat Code: The Haber-Bosch process.

We take Natural Gas (Stock Exergy), burn it to create high heat and pressure, and force atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia fertilizer.

We then spray this "fossil energy" onto the soil.

Rising desertification shows we can’t keep farming with fossil fuels

Rising desertification shows we can’t keep farming with fossil fuels

The Physics of the Soil: Dirt is treated as an inert substrate, or a sponge to hold the chemical energy.

The Entropy: The soil biology is bypassed or killed by chemicals, the soil loses its structure.

Erosion: Topsoil blowing away is literally physical Entropy (order turning to chaos).

Runoff: Fertilizers leaching into waterways represent wasted Exergy and environmental degradation.

In industrial agriculture, we consume approximately 10 calories of fossil fuel energy to produce 1 calorie of food energy.

Efficiency: Negative. The system destroys more exergy than it captures.

Regenerative Coefficient: 0. (Natural gas is only used once).

Verdict: This is a mining operation, not a farming operation. We are mining topsoil and gas to create corn.

The Regenerative Model: The Biological Battery (The Cyclical Approach)

Regenerative agriculture fundamentally changes the physics. It treats the soil not as a sponge, but as a Battery.

The Input: Sunlight (Flow Exergy).

The Mechanism: Photosynthesis. Plants pull CO2 from the air and push sugars, down into their roots to feed soil microbes.

The Storage: These microbes build Soil Organic Matter (SOM).

Thermodynamically, SOM is stored energy. It is "Negative Entropy." It represents structure, water-holding capacity, and nutrient density created from chaos.

The Cycle: Animals graze the plants, returning nutrients via manure, which feeds the microbes, which feed the plants.

Efficiency: Variable yields, inputs are free Sun/Rain.

Regenerative Coefficient: 1.0 The sun rises every day; biology self-replicates.

Verdict: The "Water Wheel." It captures a flow and uses it to build the structural integrity of the system.

With high quality petroleum running out in the next 50 years, the world governments and petrochemical industry alike are looking at biomass as a substitute refinery feedstock for liquid fuels and other bulk chemicals. New large plantations are being established in many countries, mostly in the tropics, but also in China, North America, Northern Europe, and in Russia. These industrial plantations will impact the global carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and water cycles in complex ways. The purpose of this paper is to use thermodynamics to quantify a few of the many global problems created by industrial forestry and agriculture. It is assumed that a typical tree biomass-for-energy plantation is combined with an efficient local pelleting facility to produce wood pellets for overseas export. The highest biomass-to-energy conversion efficiency is afforded by an efficient electrical power plant, followed by a combination of the FISCHER-TROPSCH diesel fuel burned in a 35%-efficient car, plus electricity. Wood pellet conversion to ethanol fuel is always the worst option. It is then shown that neither a prolific acacia stand in Indonesia nor an adjacent eucalypt stand is “sustainable.” The acacia stand can be made “sustainable” in a limited sense if the cumulative free energy consumption in wood drying and chipping is cut by a factor of two by increased reliance on sun-drying of raw wood. The average industrial sugarcane-for-ethanol plantation in Brazil could be “sustainable” if the cane ethanol powered a 60%-efficient fuel cell that, we show, does not exist. With some differences (ethanol distillation vs. pellet production), this sugarcane plantation performs very similarly to the acacia plantation, and is unsustainable in conjunction with efficient internal combustion engines.