Evolution of freedom

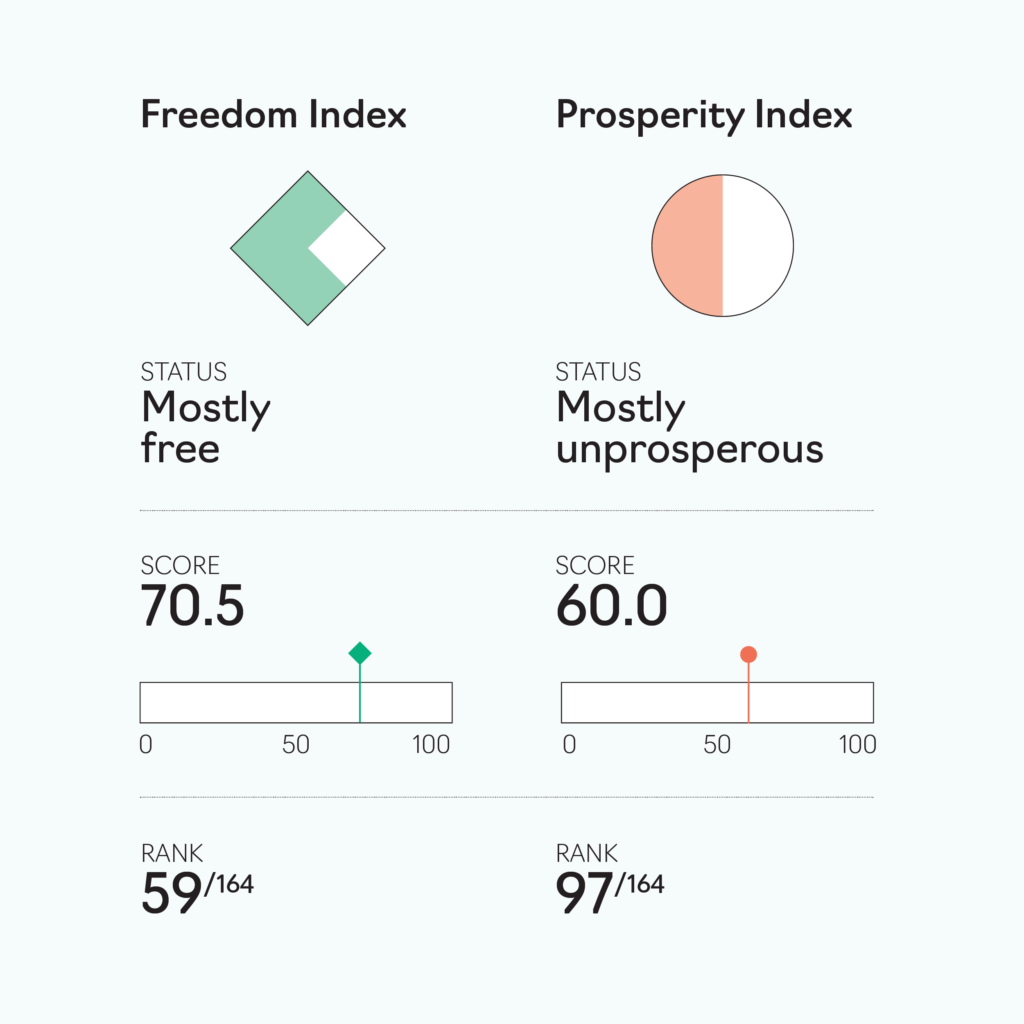

The gradual deterioration of freedom in South Africa, which started in the early 2000s and is reflected in the Freedom Index, encapsulates the evolution of the country. Regarding economic freedom, the severe drop in investment freedom is very likely due to the introduction of legislation requiring foreign investors to have local partners, and to give away equity on a large scale. The application of such requirements to more and more sectors explains the continuing erosion of investment freedom up until today.

The ability to move capital in and out of the country has been static or has slightly improved. Similarly, trade freedom has not suffered big changes during the period of analysis, and that is well captured by the flat trend of this indicator. The short-run fluctuations are probably due to the changing trade agreements with the European Union (EU), but these are modest. The slide in property rights protection that started around 2012 is explained by the introduction of efforts to amend the constitution to allow for “expropriation without compensation” of agricultural land. While a strong majority favored the amendment, parties could not agree on the specific way such a policy would be carried out, and it was finally left aside. Nonetheless, it obviously continues to be a major threat in the near future, as the African National Congress (ANC) is likely to lose its majority and may revert to a populist alliance that would raise the issue again.

The significant increase in women’s economic rights, up to an almost perfect score, may be correct at a legislative level. Nonetheless, the real situation may be worse for at least two reasons: First, the levels of criminality, and particularly gender-based violence, are today at an all-time high, which clearly reduces women’s actual freedom. Second, even if there are no legal restrictions on women’s participation in economic affairs, social and traditional norms may still severely limit their opportunities in some areas of the country. Consequently, the positive push that this indicator gives to the aggregate economic freedom subindex may be somewhat artificial, implying that the real trend in overall economic freedom is probably worse than currently shown.

The political freedom subindex shows a very flat trend, but with a mild deterioration apparent in the last few years. The evolution of the indicators in this subindex can shed some light on what is going on. Elections and political rights scores are very high in South Africa, and the slight negative trend may be attributed to political polarization, but overall, the electoral process and its guarantees are not severely affected. The “legislative constraints on the executive” indicator has a clear upward bump in the 2013–19 period, which probably reflects the failure of parliament to act on allegations of state capture during the presidency of Jacob Zuma. The publication of the State of Capture report in 2016 resulted in a national scandal, and the rejection of its conclusions by Zuma, who was later chastised by the Constitutional Court, and this may explain the initial increase on this indicator. The establishment of the Zondo Commission in 2018 can account for the additional increase up until 2020. The post-2020 fall can be explained by the failure of the state to take action against the many individuals exposed for corruption before the Commission, and the impunity with which COVID-19 funds were looted by senior officials. Hence, the fall after 2020 is capturing the failure of the government to implement the recommendations of the Commission in any meaningful way. Nonetheless, the very marked upward bump shown in the data, between 2015 and 2019, seems rather unrealistic as no specific legislative changes were introduced on this front.

A second clear fact highlighted in the political freedom data is the significant worsening of civil liberties since 2019. Government actions during the COVID-19 pandemic are surely behind the initial drop. The empowerment of the army to stop and search individuals as a means of restricting the spread of the disease generated many abuses, and even deaths in some encounters. The health restrictions imposed in South Africa—such as the prohibition on buying certain goods, and the severe lockdowns and limitations on free movement—were probably among the strictest in the world. It is not surprising that, even after lifting the COVID-related restrictions, South Africa’s score on civil liberties protection has not rebounded and has actually worsened. This is because, in recent years, there has been a strong move against civil society in proposed legislation. For example, legislation is planned that would require nongovernmental organizations to apply for state security clearance to prove that they are not acting in favor of foreign powers.

The visible deterioration of legal freedom in South Africa since 2008 is notable. In 2009 Jacob Zuma acceded to the presidency and, very early in his mandate, he started to appoint close collaborators to senior positions across the criminal justice system in an effort to protect himself and his cronies against prosecution. The indicator on bureaucracy quality and corruption adequately shows the erosion and capture of the state apparatus. Judicial independence being relatively high and constant throughout the period of analysis may be faithfully reflecting the fact that the High Court and the higher levels of the judicial system have been able to prevent their capture by the executive. But it is also very true that the judicial system in South Africa is not as efficient for the average citizen, and this fact may not be fully captured by this indicator. It could be that the decline in the clarity of the law since 2010 is picking up the overall uncertainty and opacity of the judicial process in regular cases, due to inefficient and very slow courts.

From freedom to prosperity

The Prosperity Index seems to portray a picture that is the complete opposite of my reading of South Africa’s recent development trajectory. The Index shows a fall in prosperity between 1995 and the global financial crisis of 2007–08, followed by a recovery in the last fifteen years. Instead, I believe that the first half of the period of analysis was relatively positive for the country, while the last ten to fifteen years saw a clear deterioration. A closer look at the indicators that make up the Prosperity Index shows that it is mainly the evolution of the health indicator that is shaping overall prosperity. Therefore, it is probably more enlightening to analyze each indicator separately than to rely on the aggregate score.

The evolution of income per capita somewhat vindicates my argument. Gross domestic product (GDP) growth was strong and stable up until 2007, thanks to a substantial reordering of the public sector budget. On the one hand, there was some fiscal tightening and consolidation through reduced overspends. On the other, President Mandela (in power 1994–99) introduced several social programs that had an important redistributive effect. President Mbeki (1999–2008) continued this policy path and South Africa achieved positive GDP growth rates for several years in the early 2000s. Another crucial factor that fueled South Africa’s economic success in this period was a substantial decline in the cost of borrowing. With the election of Nelson Mandela in 1994 and the transition to a fully democratic system, South Africa’s credit rating was upgraded from close to junk to AAA. The increased borrowing capacity of the South African government helped create a quite substantial movement into the middle class, especially among black South Africans, who gained access to public sector jobs with rising wages. The resignation of Mbeki and the accession to power of Jacob Zuma, together with the worsening international environment during the 2007–08 financial crisis, halted abruptly the positive economic growth rates of the previous decade, and started a period of stagnation. The rating of South African debt deteriorated again and made further pay increases for public servants and other redistributive policies unsustainable.

The drastic dynamics of the health indicator are driven by the extremely different approaches to AIDS of Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma. The former was a denialist and refused to deal with AIDS for most of his term, relenting only once the courts ruled against him near the end of his presidency. When Zuma took office, the government finally accepted that AIDS was a major problem, and a comprehensive health policy was instituted to begin fighting the disease. This shift—combined with the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which began in 2003—played an important role as well in the dramatic increase in life expectancy from 2006. The severe impact of COVID-19 in South Africa, clearly greater than the average for Sub-Saharan Africa, does not necessarily imply a worse handling of the pandemic in the country. This is because COVID-19 disproportionately affected individuals with preexisting conditions, who represent a much greater share of South Africa’s population than is the case for the rest of the region. South Africa has a relatively higher cohort with so-called “first-world diseases” like diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and so on, all of which contributed to higher mortality rates during the pandemic.

30 Years into democracy: How has South Africa's agricultural sector performed?

30 Years into democracy: How has South Africa's agricultural sector performed?

South Africa is a very unequal country, and the significant deterioration in terms of inequality during the first half of the period of analysis is very plausible. The main reason for such poor numbers is the dysfunctional labor market, including high levels of unemployment. There is a great divide in South Africa between those with a job and those without one. The expansionary policies of Mandela and Mbeki were intended to reduce inequality; they succeeded in expanding middle-class wealth but failed to deal with the growing number of people “outside” the labor market. Today South Africa has roughly three million civil servants, which represent close to half of the total number of taxpayers in the country. This somewhat artificial middle class that emerged since 1994 pulled away from those with limited job opportunities, worsening inequality. There were also some cases of incredible wealth creation among a very tiny elite, which widened the distribution even further.

The improvement in environmental quality is not impressive, clearly slower than the rest of the region. This is probably due to the fact that fossil fuels and solid fuels are still heavily used, especially among poorer households with no access to cleaner energy sources, as electricity generation has foundered. South Africa still operates a large fleet of coal-fired power stations and a fleet of carbon-intensive diesel generators, as the country has been unable to effectively transition to renewable sources of energy. So, the rise in this indicator may be more attributable to the fall in large industrial operations in the country than to a comprehensive policy focus towards a cleaner environment.

The important increase in the education indicator, of more than 20 points in the last twenty-five years, captures the massive push to increase enrollment rates at all levels of the educational system. Preschool has been an important policy focus, but also there has been a very substantial increase in fee subsidies for university students, so years of schooling are increasing at the intensive and extensive margins. Nonetheless, when we look at the quality of education, the assessment is not so positive. The standards required to pass to the next grade have been dramatically lowered. The deterioration in the quality of the education received by pupils is evidenced by the scores in global benchmarking tests, which paint a very different picture to the steady rise shown when measuring years of schooling.

The future ahead

The near future for South Africa will be determined by the evolution of the political situation. It is all about getting the politics right. The upcoming election in 2024 is going to be crucial for the country. It is very likely that we are going to see a change from a dominant party system to a coalition system. This may lead to some political instability in formal politics and parliament, but it will also lead to greater accountability and more political competitiveness. The direction the country will take is not obvious and will depend on which party or parties enter into coalition with the ANC, which is likely to remain the single largest party. The risk of the radical left party entering government is clear, with its support for arming Russia with South African weaponry, expropriation of whole sectors of the economy, and so on. If the ANC continues looking to the Communist Party and the trade unions for support, and builds a coalition with the populist left, there is a substantial risk of heading towards a downward political spiral, a rise of populism, and a sharp fall into a situation similar to that of Venezuela. Instead, if the political center is able to hold its electoral territory and becomes a suitable partner for the ANC, it would offer a completely different trajectory for South Africa. There is, for the first time, a serious effort to build a pre-election pact between opposition parties, which may change the overall political calculation in favor of the center. Therefore, the electoral results of 2024, and the coalition outcomes, will be the key determinant of where South Africa will be in ten years.

South Africa’s fiscal situation is also a pressing problem that needs to be addressed if we are to avoid a major crisis. We are now on the verge of a fiscal cliff, with rising debt that will soon further constrain government spending. This will likely lead to a deterioration of the social climate, with worsening outcomes in areas like health and education. Again, a sensible government that can introduce structural reforms in the public sector and stabilize the fiscal situation, is of fundamental importance for South Africa.

Finally, South Africa’s global alignment will play a crucial role in its evolution in terms of freedom and prosperity. The importance given to being part of the BRICS group (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) is not helping South Africa as it weakens the country’s standing with other nations with whom it has a more favorable trade balance and to which it exports more finished products. The expansion of the BRICS group to include Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Argentina, and Ethiopia reinforces this negative trend. Moreover, China’s economic slowdown is leading to falling external demand for South African goods, especially minerals, threatening foreign exchange earnings. And being close to Russia and China is negatively impacting South Africa’s relations with other democracies—in the West and elsewhere—and making it more difficult to develop an exporting sector that is not so heavily dependent on China.

Greg Mills heads the Johannesburg-based Brenthurst Foundation, a think tank that seeks to strengthen African economic performance. He has directed numerous reform projects with African heads of state across the length and breadth of Africa. His latest books include Rich State, Poor State (2023), The Ledger: Accounting for Failure in Afghanistan (2022), and Expensive Poverty (2021), as well as a volume on South African scenarios, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (2023).