Scientists have come up with some theories about how the continent of Africa is splitting in two.

If you were to look at the Earth tens of millions of years ago, it would look very different from the blue and green space marble we call home today.

Countries like Zambia and Uganda, which are currently landlocked, could one day have their own coastlines due to the East African Rift.

The rift has received more media attention in recent years, following a sudden large crack that appeared in Kenya in 2018.

This crack caused massive destruction in the south-western part of the country, and lead to part of a local highway collapsing.

There has been an ongoing debate as to what was the cause of this crack, with some arguing it was directly caused by the East African Rift.

However, some geologists have said it was due to soil erosion.

Postdoctoral researcher at Royal Holloway University of London, Lucía Pérez Díaz suggested a combination of two. She said the crack could also be because of the erosion of soft soils infilling an old rift-related fault.

The most important question, however, is why this is happening.

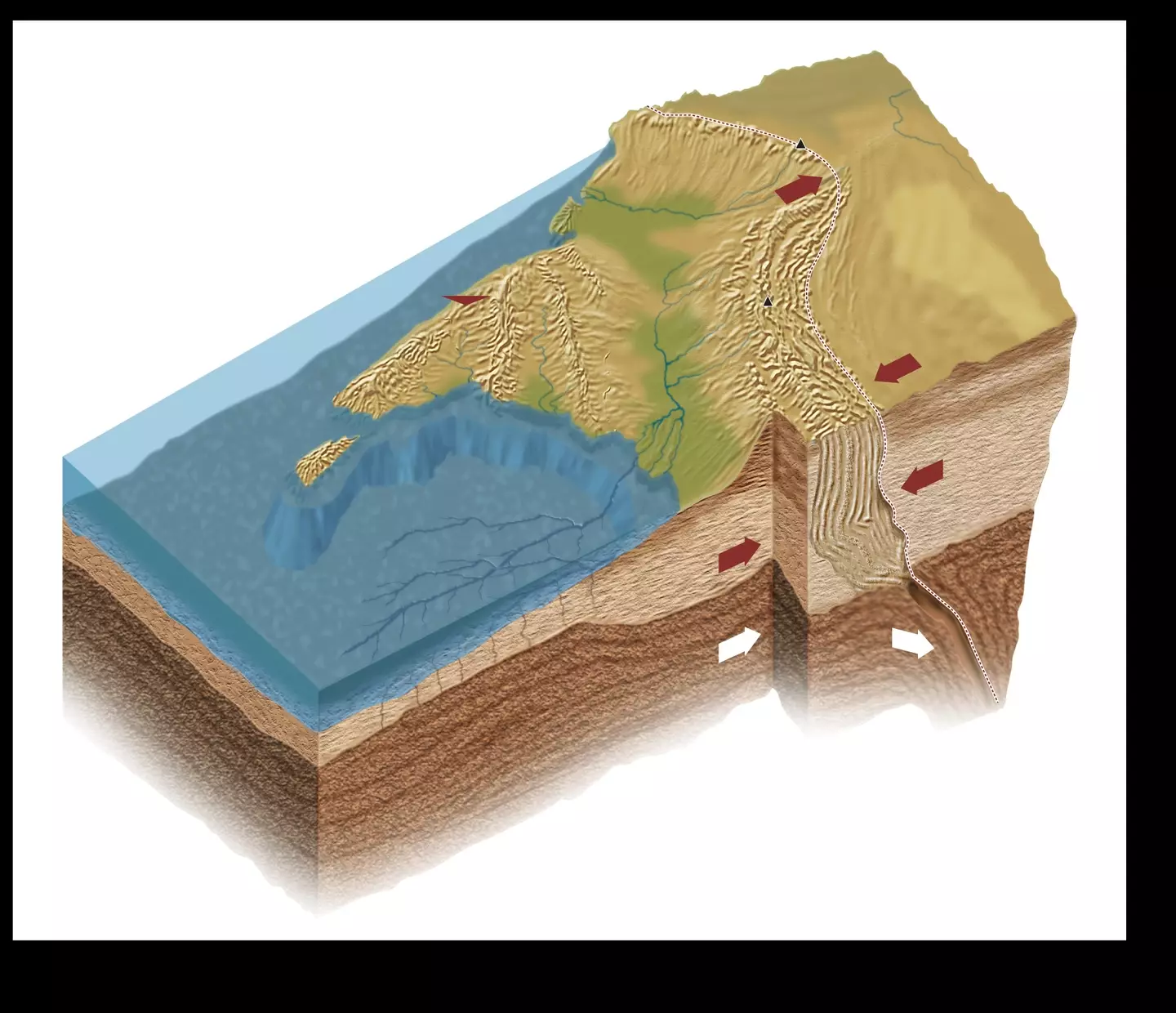

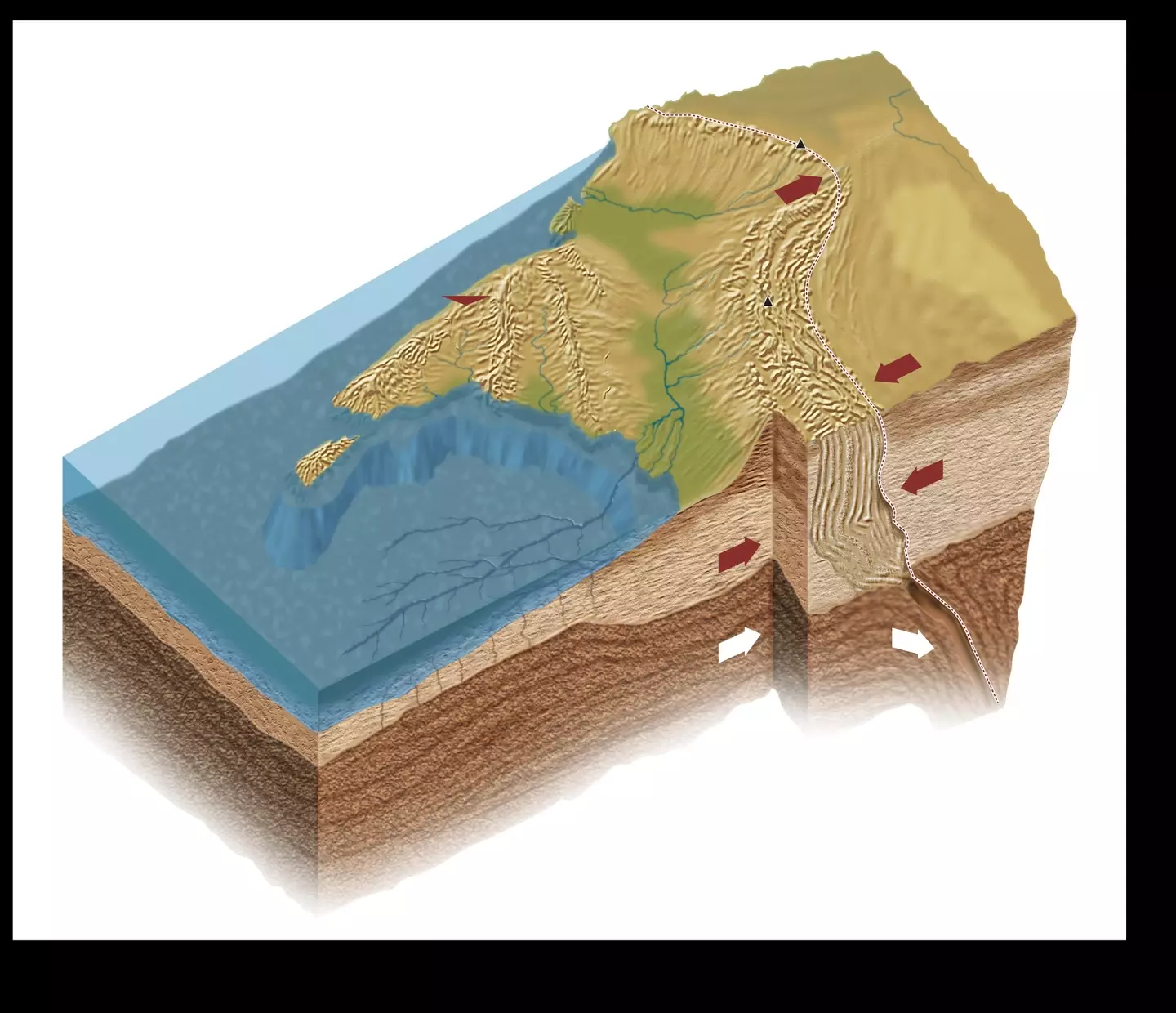

While the Earth’s changes may not seem noticeable to us, tectonic plates are constantly moving.

The Earth's lithosphere, which is formed by the crust and the upper part of the mantle, is broken up into a number of these tectonic plates.

As mentioned, these plates are not stationary, and the movement causing them to move around can also rupture.

This can lead to a rift forming and the creation of a new plate boundary, which Diaz says is happening at the East African Rift.

The East African Rift itself stretches over a staggering 3,000km from the Gulf of Aden in the north towards Zimbabwe in the south.

As a result, it splits the African plate into two unequal parts: the Somali and Nubian plates.

The rift has varying different attributes across its 3,000km distance, with the south seeing faulting occur over a wider area, and volcanism and seismicity are limited.

But if you head towards the Afar region, the entire rift valley floor is covered with volcanic rocks.

Diaz suggested that this means the lithosphere has thinned almost to the point of complete break up.

This means over a period of tens of millions of years, a new ocean will lead to seafloor spreading along the entire length of the rift, which is apparently beginning to happen already.

After this the ocean will then flood in, ultimately leaving the African continent smaller and a large island made of parts of Ethiopia and Somalia sitting in the Indian Ocean.

The Himalayan mountains are a vast area that covers five countries: India, Pakistan, Nepal, China, and Bhutan.

The mountains began forming over 50 million years ago and continue to today as the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates continue to collide, pushing the peaks slightly higher each year.

However, according to a 2023 study by a team of geophysicists, significant tectonic movement beneath the mountain range could split one of the countries in two.

The study - led by Lin Liu, Danian Shi, Simon L Klemperer et al. - started by investigating the levels of helium present in the Tibetan springs and found a new development surrounding the underneath plates.

Helium levels were found to be higher in southern Tibet than in northern Tibet.

Using '3D S-wave receiver-functions', one of the images showed evidence of the top and lower slabs of the Indian Plate appearing to detach.

This led to the discovery that the two plates appear to be 'underplating' or 'subducting' beneath' a mantle wedge. '

"Our 3D S-wave receiver-functions newly reveal orogon-perpendicular tearing or warping of the Indian Plate." the study reads.

"Our SRFs objectively map depths to distrinct Indian and Tibetan lithosphere-asthenosphere boundaries across a substantial region of south-eastern Tibet.

"The inferred boundary between the two lithospheres is corroborated by more subjective mapping of changing SWS parameters, and by independent interpretations of the mantle suture from mantle degassing patterns and the northern limit of sub-Moho earthquakes.

"The southern limit of Tibetan lithosphere and subjacent asthenosphere is at 31°N west of 90°E but steps south by >300 km to ~28°N east of 92°E likely representing a slab tear."

This activity means the Indian plate would peel into two instead of break.

It has also identified a potential heightened risk of earthquakes along the plate boundary.

It has also been suggested the upper part could pop up and cause Tibet to rise higher, leading the lower half to sink further into the mantle.

Douwe van Hinsbergen, a geodynamicist at Utrecht University, spoke to Science about the study's potential impact.

"We didn't know continents could behave this way and that is, for solid earth science, pretty fundamental," he said.

Geodynamicist Fabio Capitanio at Monash University also reiterated that the study had not yet been peer-reviewed, but it was the type of work that needed more investigation.

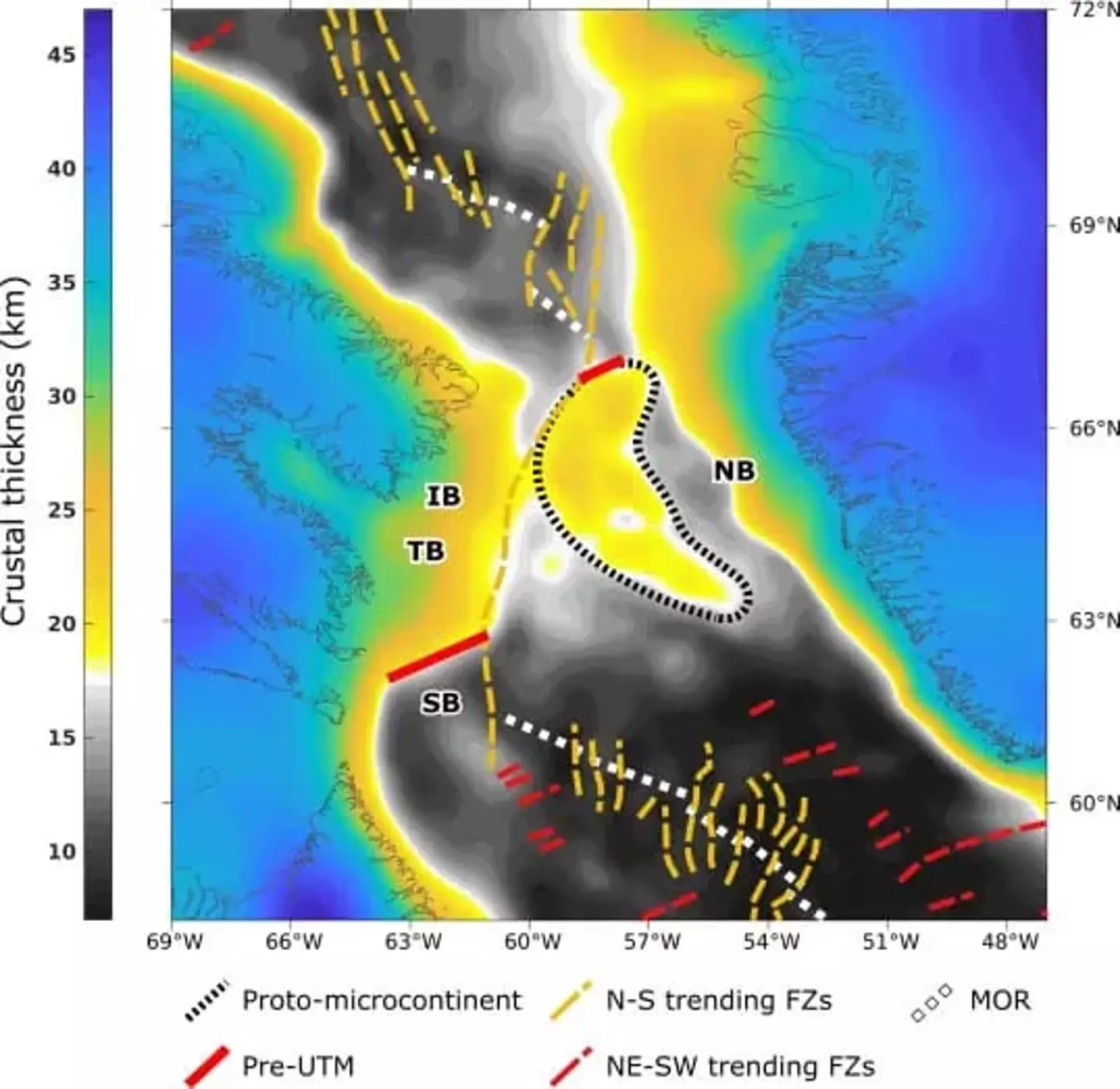

Scientists have discovered a new microcontinent which they believe was formed 60 million years ago.

The incredible discovery was made by researchers Luke Longley and Dr. Jordan Phethean, from the University of Derby in the UK, as well as Dr. Christian Schiffer from Uppsala University in Sweden.

The microcontinent, which is located between Canada and Greenland, is 250 miles long and is sitting below the Davis Strait, which connects the Labrador Sea in the south with Baffin Bay in the north.

The discovery was made while the team were examining the area's tectonic plate activity and now, a study into its formation has been published in Gondwana Research.

Can Africa one day help feed the world’s growing population?

Can Africa one day help feed the world’s growing population?

"Rifting and microcontinent formation are absolutely ongoing phenomena—with every earthquake, we might be working towards the next microcontinent separation," Dr. Jordan Phethean told Phys.org.

"The aim of our work is to understand their formation well enough to predict that very future evolution."

It's believed that the microcontinent could have started to form 118 million years ago.

The team explain that microcontinents are 'related regions of relatively thick continental lithosphere separated from major continents by a zone of thinner continental lithosphere'.

Although the rifting first began 118 million years ago, scientists think the seafloor spreading began around 61 million years ago before the continent became totally separated around 33 million years ago.

The incredibly important research could be vital in understanding how other microcontinents are formed.

“Better knowledge of how these microcontinents form allows researchers to understand how plate tectonics operates on Earth, with useful implications for the mitigation of plate tectonic hazards and discovering new resources,” said co-author Dr Jordan Phethean.

Meanwhile, geologists are convinced that a new ocean is being created in Africa as the continent continues to shift apart.

Countries like Zambia and Uganda, which are currently landlocked, could one day have their own coastlines due to the East African Rift.

The rift has received more media attention in recent years, following a sudden large crack that appeared in Kenya in 2018.

Some scientists have suggested that this is due to the African tectonic plate breaking in two.

But this is not the only theory that geologists have about the how the crack has formed.

Others have suggested that the cause could be soil erosion.

The rift means that over a period of tens of millions of years, a new ocean will lead to seafloor spreading along the entire length of the rift, which is apparently beginning to happen already.

India is the seventh largest country in the world, coming in behind the likes of Australia, Brazil and the US.

It's said to be approximately 3.287 million km² and, if it was to be divided vertically - it would become two countries each around the size of Mongolia.

But India isn't thought to be splitting vertically, and scientists believe it's potentially sheering horizontally instead.

The study - titled 'Slab tearing and delamination of the Indian lithospheric mantle during flat-slab subduction, southeast Tibet' - looks into the formation of the Himalaya.

The Himalaya is a mountain range spanning over five countries - India, Pakistan, Nepal, China and Bhutan - and according to the Geological Society, 'the Himalayan mountain range and Tibetan plateau have formed as a result of the collision between the Indian Plate and Eurasian Plate which began 50 million years ago and continues today'.

The study - led by Lin Liu, Danian Shi, Simon L Klemperer et al. - started by investigating the levels of helium present in the Tibetan springs and presented a new theory about the plates that lie underneath the mountain range.

The study found the levels of helium were higher in southern Tibet compared to northern Tibet, suggesting the Indian tectonic plate is splitting in two underneath the Tibetan plateau.

The study then used '3D S-wave receiver-functions' to analyze the Indian Plate.

The receiver function technique works by using information from teleseismic earthquakes to image the structure of the Earth and its internal boundaries.

The study details, as published in ESS Open Archive: "Our 3D S-wave receiver-functions newly reveal orogon-perpendicular tearing or warping of the Indian Plate."

One of the images appeared to show evidence of the top and lower slabs of the Indian Plate appearing to detach.

This subsequently suggests the Indian Plate is 'underplating' or 'subducting' beneath a 'mantle wedge'.

The study resolves: "Our SRFs objectively map depths to distrinct Indian and Tibetan lithosphere-asthenosphere boundaries across a substantial region of south-eastern Tibet.

"The inferred boundary between the two lithospheres is corroborated by more subjective mapping of changing SWS parameters, and by independent interpretations of the mantle suture from mantle degassing patterns and the northern limit of sub-Moho earthquakes."

Basically, this means the Indian Plate would peel into two, opposed to breaking into two.