A real-time map, created using satellite data, aims to show which dams could be dangerous - but the site will go dark by the end of the month as government funding runs out.

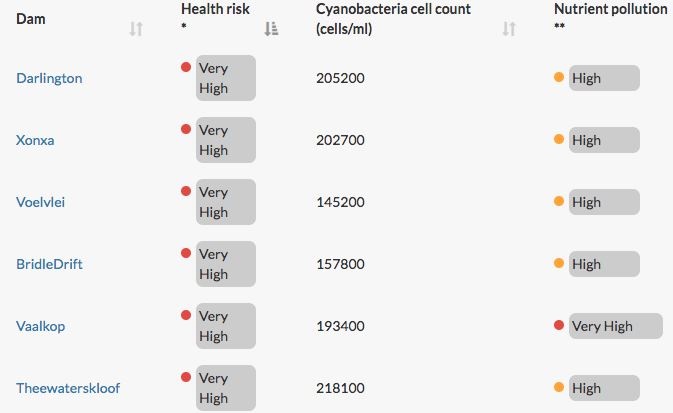

A real-time map of nutrient pollution in more than 100 dams in South Africa shows that two in five could pose high health risks from toxic algae, and about half are not safe to swim in.

Cyanolakes, a South African company that specialises in determining water quality and algal bloom from satellite data, created the map. It was developed as part of the Earth Observation National Eutrophication Monitoring Programme, funded by the Water Research Commission. But the government funding has run out, and at the end of this month be information will no longer be free.

South Africa has the highest number of dangerous tailing dams—structures constructed, often by mining companies, to store waste in liquid form. The dams are considered hazardous if improperly handled and have resulted in environmental disasters and deaths many times around the world.

Wider environmental hazards arising out of mining operations in South Africa, and elsewhere in Africa, range from river contamination from chemicals used in mining processes to improper rehabilitation of mined out operations. Tailing dams have emerged as the latest significant environmental risk factor from mining and South Africa has the highest number of the riskiest of these, according to an investigative report by Reuters.

As the risk of collapse of these dams looms, South Africa still has memories of the collapse of a tailing dam at Merriespruit in 1994 which killed 17 people after flooding a Free State surbub. In 1974, another tailings dam at Bafokeng also failed. Only recently, a tailings dam operated by Vale in Brazil collapsed, driving a slurry of mining waste downstream towards a small town in the countryside and bringing environmental contamination.

There are three common types of tailings dams; Upstream tailings dams which are considered cheap but risky owing to the chances the toxic mining waste behind the dam structure erodes and weakens the structure, causing it to rupture; Downstream tailings dams which provide a minimal cover to the risk of collapse as they are designed to be stable but are more expensive to construct. The third and relatively efficient type is known as Drystacking and provides for greater opportunities to recycle the water from the waste contained in the tailing dam.

Now, of all the 262 high risk tailing dams in the 10 countries profiled by Reuters, the majority are located in South Africa with their architectural method considered to construct them deemed “unsafe by many engineers”. South Africa has a massive 52 active high risk tailings dams and a further 27 which are inactive, meaning they are currently not being used.

The South African mining companies say they are taking action, with Mark Cutifani, chief executive officer of Anglo American which holds big mining firms in South Africa, saying in 2019 that the company is now working on technologies expected to significantly decrease the volume of waste material produced from mines. These technologies leave less waste, allow for de-watering of tailings and offer energy options as well as water usage reductions.

In South Africa, there are growing calls for the cleaning up of the high risk tailings dams so that the waste can be re-processed and used to fill up mined out operations, thereby reducing environmental hazards. This is an approach that experts believe can help preserve natural water bodies by removing the contaminated tailings material.

“We can reduce the volume of waste and the toxicity of waste by using new technology available to us. The old days of closing and grassing over are unsustainable; we need to transition from one form of economic activity directly to another,” says Nikisi Lesufi, senior executive environment, health and legacies at the Minerals Council South Africa.

A 2014 study found that 50% of South Africa’s water bodies had pervasive toxic algae, which thrived due to eutrophication. Eutrophication is an excess of nutrients in the water, often caused by fertilizer and sewage run off, among other factors. This bacteria can be toxic to humans and animals.

Mark Matthews, founder of Cyanolakes, produced the 2014 study as part of his doctorate. He developed a method to determine the quantity of algae in water bodies from satellite data, and used it as the basis for Cyanolakes. This technique “allows [water utilities and companies] to monitor their water more effectively than traditional methods”, he says.

“[The map] is really about providing real time online service which gives you info about cyanobacterial blooms in the interest in protecting public health,” he says. “There is tons of satellite data, but it is sitting there doing nothing. We wanted to use that and serve it up so that the public can make decisions.”

The department of water and sanitation said it was considering options for the project. "We are however restricted by available budgets and no decision has yet been made," said Gerhard Cilliers, scientific manager for resource quality monitoring at the department.

Asked if the South African situation had gotten worse since his PhD, Matthews says that it is about as bad as it was then. “The thing is, it is quite difficult to make generalisations.”

But he notes that the current levels are those for Spring. “[The quantity of algae] will be higher in summer. When the most people are in the water, it will be the worst.” Business Insider.