Climate change requires rapid, major and systemic economic changes at the local, national and global levels.

Food supply is estimated to account for about a third of greenhouse gas emissions. African countries, however, are responsible for negligible emissions, yet face urgent challenges of adaptation to global warming and extreme weather events which threaten production.

A just transition must address the adaptation challenges of African countries while also moving food systems onto a sustainable footing with lower emissions. These changes all work through market mechanisms.

Large incumbent firms have typically invested and innovated to build up their market positions. At the same time, to borrow Warren Buffett’s metaphor, they build moats around their positions to protect themselves and their profits from rivals.

First, the rapid change in food systems means business models have to change and this may well be led by disruptors, as we have seen in other sectors such as motor vehicles. Incumbents are naturally invested in current production systems, have the most to lose from systems changes and are likely to delay and try to control the process of change. Conversely, dynamic competition which opens markets up to disruptors can be a powerful positive impetus for change, including by incumbents if and where they can pivot.

Second, to win broad-based support, climate change measures need to be fair. This means that we must tackle inclusion along with the transformation in production systems. Competition law and policy are important tools to work for inclusion. They can tackle the market power and anti-competitive practices that mean smaller market participants, including farmers, are undermined and have their returns squeezed by powerful suppliers and buyers.

Vulnerability to agriculture and food systems impacts

African farmers are among the most vulnerable to extreme weather. Southern Africa, in particular, is a climate “hotspot” where temperatures are increasing above the global average and rainfall is projected to decline further. This is notwithstanding good rains in South Africa in 2021 which risk lulling us into complacency. Meanwhile, Kenya is experiencing drought and high food prices and Brazil faced the worst drought in close to a century in 2021 under the La Niña weather cycle. This cycle is continuing in 2022, bringing substantially higher food prices around the world.

South Africa urgently needs to face up to the challenges and provide leadership on the continent to tackle the risks. The country will be hit by another El Niño cycle in coming years, like that which brought the drought of 2015-16, but it is likely to be much worse. Meanwhile, the overall warming continues.

The good news is that the wider southern Africa region is blessed with enormous potential for agriculture, including water and land in countries such as Zambia and Tanzania. With cooperation, investment and appropriate policies this potential can be realised in resilient regional value chains, creating jobs and growing economies across the region.

At the same time, the food produced needs to be healthy, nutritious and affordable. However, South Africa and other African countries face a massive and growing “double burden of malnutrition”, with high levels of obesity alongside stunting and wasting. Substantial proportions of the population cannot afford enough calories, while many others are buying excess calories in the form of ultraprocessed food which is high in sugar and fat but not nutritious. Markets that deliver cheap and convenient food but with low nutritional value are fundamentally failing and impose huge health costs.

For the required food transition to be just, we therefore need to address the interconnected and concentrated nature of the global food system to empower groups with limited resources through inclusive and fair processes to ensure healthy markets.

Engaging with economic power in food value chains

Food systems are highly governed – privately and publicly. Food is produced and marketed through hyper-globalised and highly concentrated international food value chains running from agricultural inputs right through to the advertising campaigns and retailers that shape our consumption choices. This matters because for measures to be effective in achieving the food systems transformation, the rules must reshape markets to incentivise changes by the large corporations as well as the challenger firms. The extensive food standards and regulations need to be fit for purpose to ensure healthy market outcomes and investments in the transformations needed.

In South Africa, as it is globally, key markets are dominated by a relatively few companies – and the just food transition needs to engage with them. From seeds and other farming inputs through to processing and retail, there have been substantial increases in concentration globally, including through hundreds of mergers. In the supply of grain seed in South Africa, concentration is among the highest in the world, as four or fewer companies account for almost all sales of maize, soybean and sunflower seed. The picture is similar for agrochemicals, globally and in South Africa. In agro-commodity trading, the major companies are integrated upstream and downstream, such as into feed and meat production.

Supermarkets and major food-processing companies shape consumer choices. These companies need to be part of the solution. In South Africa and the southern Africa region, a handful of large supermarket chains are important gatekeepers for food processors to access end consumers. With growing store networks extending beyond urban areas, and increasingly into peri-urban and rural areas, these supermarket chains enforce both mandatory and private standards which influence the availability, safety and quality of food on shelves. They also influence other attributes that affect consumer purchasing decisions, such as packaging, promotions, advertising and positioning on shelves.

In South Africa, five national supermarket chains control 64% of the grocery retail market. These chains have significant buying power, particularly in their relationships with small and medium enterprise (SME) food producers, and are able to dictate terms and conditions of sale. SME food processors are often pushed to sell through alternative routes to market, given the high costs and risks they face in supplying the main supermarket chains. Often only a few large, multinational and diversified food-processing companies are able to meet the requirements of supermarket chains. Food processing experiences similarly high levels of concentration in many products in South Africa, and these players are also able to shape what is demanded by consumers. Concentrated food processing and retail markets limit the benefits that greater competition and diversity brings in terms of availability, cost, quality and choice.

Food systems transformation therefore needs to engage with concentration and integration if it is to address sustainability and inclusion together, through deliberately reshaping value chains for food security, resilience and health. This requires adding agency and sustainability to the four key food security pillars of availability, access, utilisation and stability. The transformation is not anti-business – it is essential for the future of businesses and markets.

Engaging with firms means recognising the many dimensions of their influence and how rules can work most effectively to channel incentives towards the transformations required. One aspect of economic power is market power – where firms can charge high prices that exploit consumers. Powerful firms can also exclude rivals by, for example, controlling access to key inputs or marketing channels, as highlighted above.

The market power of large firms is tempered by competition and generally requires effective competition enforcement to ensure that markets are open and fair. Competition means farmers have options to sell their produce and in sourcing inputs. Smaller agro-processors have alternative routes to market for their products and are not reliant on a very few large retail chains.

Economically powerful firms further use their influence to lobby and to govern value chains such as by setting standards, shaping regulations and acting as gatekeepers Competition means that this power is diluted and governments are less susceptible to capture by concentrated business interests.

South African competition cases have shed light on the ways positions of market and economic power can be protected and extended. Control at one level of the value chain can be exerted to undermine rivals, such as through positions of substantial market power in grain storage (the Senwes case), poultry breeding stock (the Astral-Elite case) and in supermarkets’ use of exclusivity in leases in shopping malls. These cases have been tackled by the competition authorities to address discrete anti-competitive practices. However, while proscribing such conduct removes a barrier to competition, it is just one step and does not in itself create healthier competitive markets.

We need to recognise that vertical and horizontal integration in food production enables synergies to be realised, such as in providing farmers with a bundle of goods and services. It also means large firms can control who gets to participate along the different levels of production and processing that they coordinate. We need to rethink competition as part of sector policies to reshape markets for investment, growth and healthier outcomes, taking into account digitalisation and climate change.

The rethink of competition policy involves analysis of markets beyond the piecemeal investigation of discrete alleged contraventions. This can be done through market inquiries which have the power to assess the combination of factors that lead to poor market outcomes and which take steps to remedy them. The Competition Commission in South Africa is an international leader in using inquiries. Inquiries need to have the resources for authoritative, rigorous assessment and the ability to ensure that remedies are implemented. In strategic areas, inquiries can lead to enforceable codes of conduct, which are effectively tailored rules and a referee to ensure better market outcomes. Codes of conduct have been adopted in a number of countries, such as the UK and Namibia, for supermarkets in recognition of the central role large supermarket groups play as gatekeepers of supply chains and shapers of consumer choices.

Competition policies are complements to appropriate sector strategies. Government-sector strategies can work with industry bodies to transform industries for the collective benefit – building inclusion and sustainable value creation – as is exemplified by the citrus industry in South Africa .

Digitalisation, Agriculture 4.0 and effective collective action for transformation?

The digitalisation of production, marketing and delivery in agriculture and food markets increases the efficiencies that can be realised by integrated companies. It also reinforces concentration and means that market power spreads across markets.

In contrast, what has been termed Agriculture 4.0 covers advances such as vertical farming, circular agriculture and aquaponics, along with the digitalisation of food production systems. Digitalisation is enabling smart and precision agriculture solutions so that the farmer can anticipate and respond to climate-related weather changes, including through more effective water management and reduced chemical use. Farmers can meet traceability and certification requirements at lower costs, as with the Phytclean platform developed by the fruit industry in South Africa (see sidebar below). Digital tools are also improving logistics, packing and marketing functions through the value chains, lowering the costs to access markets.

The integration of the major companies, combined with the digitalisation of economic activity, makes these businesses effectively building platforms, with rich datasets coupled with logistics and agronomic and advisory capacities. This may require reconsideration of what rules and policies businesses should follow to ensure that markets are healthy and open to wider participation and that power is not exploited.

Understanding what the major firms are doing is critical. However, the increased market data being collated are mainly in private hands, tipping the balance against governments and in favour of the large corporations aggregating and analysing the data.

An agenda

The agenda is necessarily ambitious as time is rapidly running out. The creative and disruptive impetus of market participants needs to be unleashed to bring solutions that reshape value chains. We propose a four-pronged package.

First, the state needs to be an effective gardener – cultivating the soil for a diversity of firms to flourish. This involves proactively taking down the barriers that prevent small firms from flourishing. A package of measures should include access to routes to market for these businesses, providing development finance and effective support for skills and technology adoption. These are part of green and inclusive industrial policies tailored to sectors and value chains, measures that invest in shared infrastructure, advisory services and finance as part of a green industrial policy for food. Real economic transformation requires sustained support for the capabilities of black entrepreneurs and farmers.

The tomatoes at the forefront of a food revolution

The tomatoes at the forefront of a food revolution

Second, we need to elevate vigorous competition and inclusion by opening up markets. This means placing the onus on dominant firms to justify why competition will not be undermined when they make acquisitions or enforce exclusionary agreements on smaller participants. Competition authorities must be active referees, updating the rules for changes in technologies and practices and ensuring that we consider the effects of firms’ conduct across the economy. The agenda being advanced with regard to digital platforms shows the way, with changes to place the onus on gatekeeper firms not to distort competition in mergers or to abuse their market dominance.

The amendments to the South African Competition Act are important for taking into account wider participation by SMEs and businesses owned or controlled by historically disadvantaged people, and for including provisions related to buyer power. We need to go further if we are to square up to the reality of the past three decades and the enormity of the transformation challenge posed by climate change on top of the entrenched levels of inequality. We need to incentivise investment in new productive capabilities in sustainable food supply, with a diversity of approaches and business models.

The merging of competition and consumer-protection regimes should bring the authorities together under one institution. Both involve collecting information on markets, consumer decisions and firm conduct. Both bring synergies in analysis and enforcement.

Market inquiries are a powerful tool available to the Competition Commission to better understand features of markets that prevent, distort or restrict competition. Inquiries in food markets should investigate the impact of concentration on sustainable food production and distribution, as well as on access to affordable and healthy food. Efforts are under way as part of the Agriculture and Agroprocessing Master Plan to secure voluntary commitments from large supermarket chains and agro-processors to diversify their supplier bases and invest in building capabilities of SME suppliers through supplier-development programmes. However, the key role of supermarkets in organising value chains and shaping consumption may mean that a code of conduct for supermarkets and groceries also needs to be adopted as soon as possible. Ideally this should be consistent across countries in the region, learning from the experiences of those already in place such as in Namibia, Kenya and the UK.

Third, monitoring and tracking markets is essential as climate change leads to more frequent and deeper shocks. Building the package of measures to change direction will also be a process of trial and error. Both monitoring and tracking need ongoing information gathering and analysis by public bodies in order to advise the government. The monitoring needs to be of production, prices and patterns of consumption to ensure early warning of the impacts of shocks, while the tracking follows the effects of interventions. Huge amounts of these data are being collated by private market participants. The data should be accessible in the public interest (as is the case in observatories such as that of the European Union). Instead, the concentration of data in the hands of the large integrated firms has increased their lobbying power and enabled them to make large arbitrage margins and speculate in response to climate shocks.

Fourth, the food systems transformation must be a regional plan to reshape healthy value chains through a balance of cooperation and competition. The lead firms operate regionally (and globally) and the climate change impacts can be mapped across the region. Moreover, the opportunity to adapt and grow must take advantage of the abundant water resources in the region and the fact that when extreme weather events occur in some parts of the region conditions remain good in others.

The reality, unfortunately, is fragmentation of national agendas and beggar-thy-neighbour policies. South African leadership is urgently required and is in the country’s self-interest given both its vulnerability and the financial resources which can be mobilised for investment.

Future food security depends on sustainably unleashing this potential through effective regional food industrial policies. And growing economies across the region will lift South Africa. We are already behind the curve, given the climate projections, and urgently need to make investments across the region in water management, research and infrastructure to support sustainable and resilient food production.

Adaptation requires diversifying crops and the seeds suited to conditions. A “farm to fork” strategy for southern Africa requires concrete actions in key value chains, starting with poultry to animal feed and fruits and vegetables. Such a strategy can be informed by successes, notably in citrus, where there has been value creation, job creation and land reform for wealth creation.

The leading example of South African citrus adapted from Chisoro-Dube and Roberts

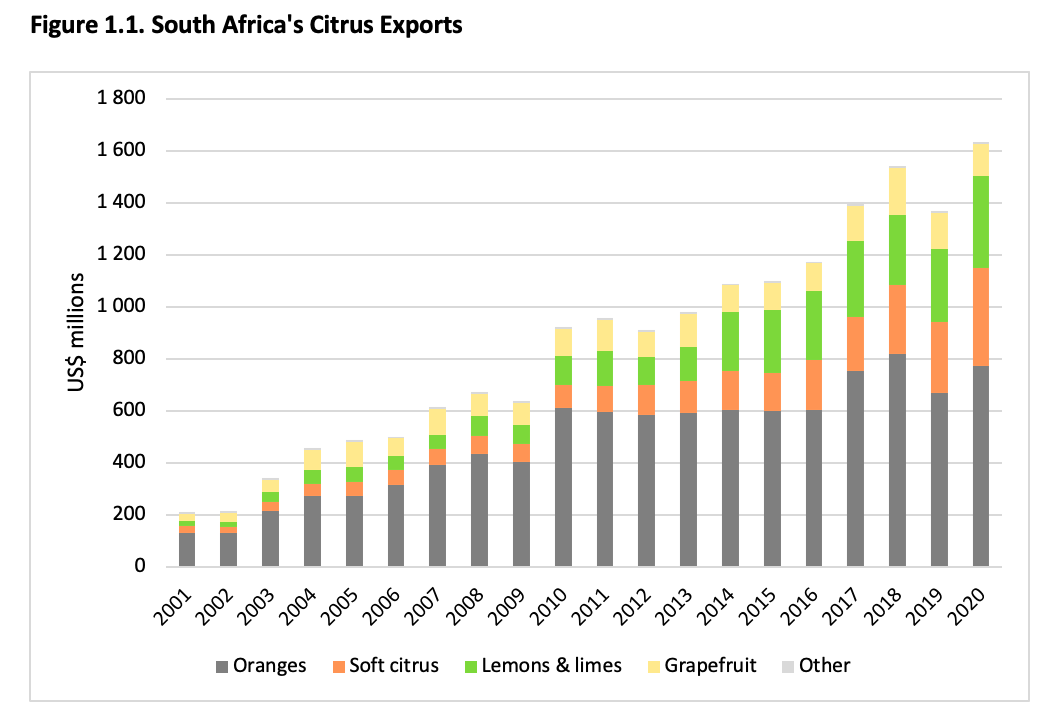

The South African citrus industry represents the huge potential gains from collective action working with government for value-chain upgrading. South Africa has grown to be the second-largest citrus exporter in the world. The success has been driven by higher-value “soft citrus” varieties along with lemons and limes, which nearly quadrupled exports from$202-million in 2010 to $730-million in 2020 (Figure 1.1). This reflects two critical points: first, the planting of trees to respond to changing global demand patterns; and second, the growing sophistication in a range of capabilities, including the cultivars being planted, compliance with phytosanitary standards, infrastructure in cold chain and logistics, and marketing.

Frequent drought conditions and the higher prevalence of pests and diseases are leading farmers to invest in cultivars that are adaptable to local conditions, coupled with new technologies in irrigation, pest control and precision farming, to maintain and improve production. Farmers have been adopting low-flow micro- and drip-irrigation technologies, including fertigation systems to fertilise and irrigate crops at the same time. Precision agriculture methods use water more efficiently and improve monitoring of trees’ nutritional needs. They also include smart spraying systems to limit the quantities of chemicals sprayed to control diseases and pests.

The role of the Citrus Growers Association (CGA) has been central in investments and coordination to support shared capabilities and upgrading over time. This includes working with government to secure market access, conduct research, provide technical support and logistics, and facilitate transformation in the industry. Closely related is the CGA’s work on digital systems to improve compliance by producers in the value chain through the development of an electronic data-sharing platform, Phytclean, for issuing export phytosanitary certification. This practice has been expanded to other fruits.

The CGA has also been entrepreneurial in establishing businesses to compete with large incumbents who otherwise would have market power over farmers. This includes the CGA Cultivar Company to develop and source new cultivars, locally and internationally. CGA also established River BioScience, which supplies crop-protection products and services in competition with multinationals such as Monsanto.

The citrus industry has combined upgrading with inclusion as the Citrus Growers Development Company works with black farmers to enter and grow in high-value export markets to ensure “land reform for wealth creation”. It demonstrates how opportunities can be realised while addressing climate change through investment and technologies coupled with market access to meet increased global demand from health-conscious consumers.