As dusk descends, the haunting lupine melody of the continent’s most underestimated carnivore cuts through the air and raises goosebumps on the skin.

THE BASICS

Nearly anyone on safari is likely to encounter a jackal at some point, often around a lion kill and very seldom at the centre of attention. They are expert opportunists and masterful lurkers with iron-clad stomachs capable of handling everything from rotten carcasses to berries and even lion faeces. As underappreciated species go, jackals are very close to the top of the African safari list. Without the rarity factor, they are generally overlooked or dismissed. This is unfortunate as they are fascinating, intelligent, social and, on occasion, clownish creatures. Besides, any animal that dares to snatch the scraps out from beneath a hungry lion’s nose should be entitled to automatic respect. They are also skilful hunters, particularly the black-backed variety.

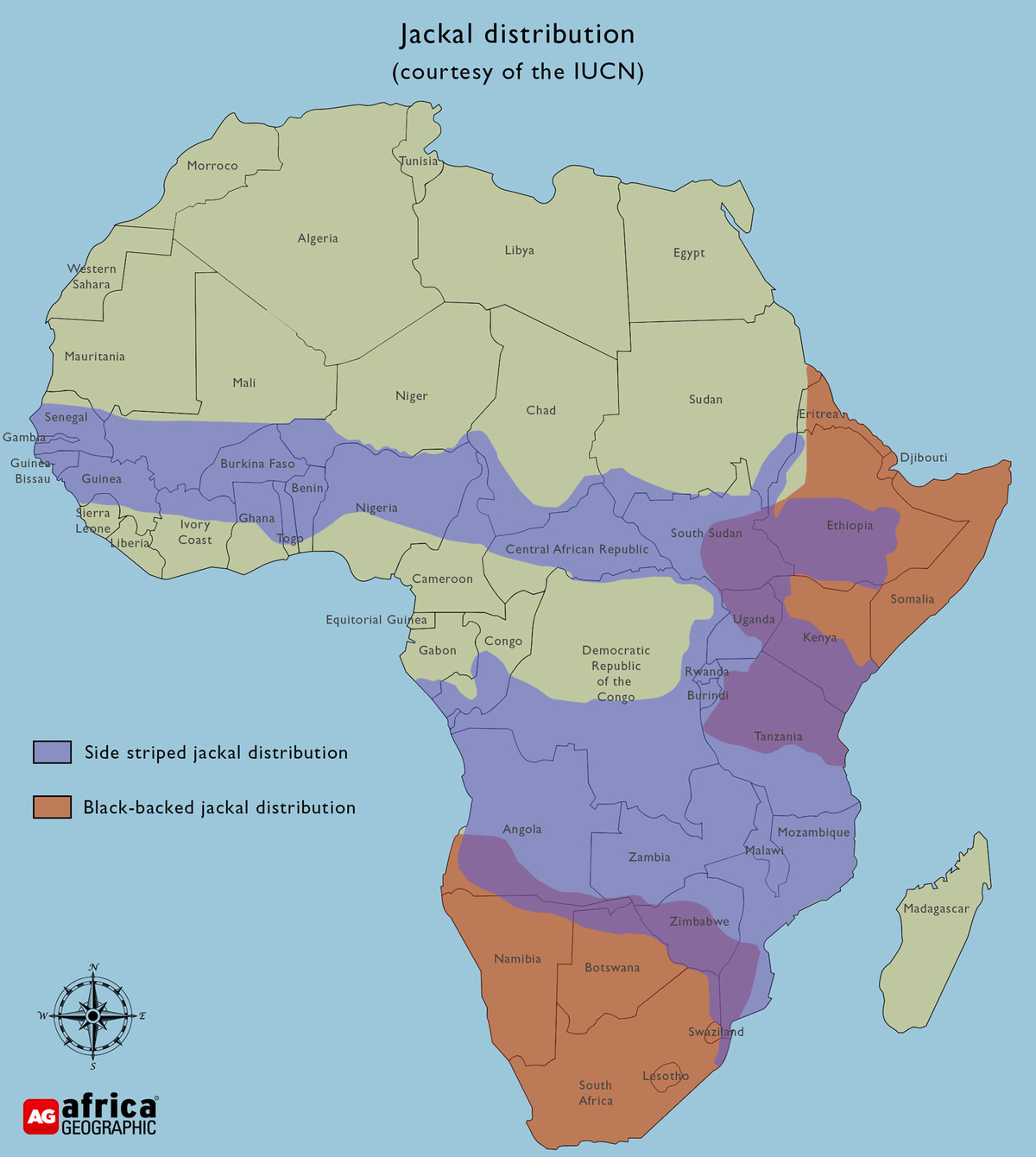

Not to be confused with foxes (of which there are several species in Africa, learn more about them here), jackals are taller and stockier than the various members of the Vulpes genus, with longer, more obviously wolf-like facial features. There are two species in Africa – the black-backed and side-striped jackal. Another species, the golden jackal, inhabits parts of southern Europe and Asia. As the name indicates, the black-backed jackal can be distinguished by the saddle of black (with white patterns) that runs across the centre of the back, while the stripe of the side-stripped jackal is often indistinct. The side-striped has the more extensive range of the two species and is found throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa. They are notably absent in the more arid areas of the southwestern part of Southern Africa, where black-backed jackals reign throughout most of South Africa, Botswana and Namibia. Where the two species do overlap (as they do across much of East Africa), the black-backed jackal seems to dominate, despite being the smaller of the two. This has often been connected to the observation that black-backed jackals appear to hunt more frequently (and hunt bigger prey) than their side-striped cousins. However, whether this is true across all populations and habitat types has yet to be confirmed.

These differences aside, there are several species similarities. Both jackals are omnivorous, with plant matter accounting for over 50% of their diet in some places. They are also both monogamous and territorial.

QUICK FACTS

| Black-Backed Jackal | Side-Striped Jackal | |

| Mass | 6-13kg | 6.5-14kg |

| Shoulder height | 38-48cm | 35-50cm |

| Social Structure | Monogamous, small family groups | Monogamous, small family groups |

| Gestation | Just over two months | Just over two months |

| Number of pups | One to nine pups | Three to six pups |

THE LIFELONG COUPLE

As they are monogamous, there is minimal sexual dimorphism between male and female jackals. The bond between mated pairs is profound and may last for several years – usually the duration of their lifespan. The couples are almost inseparable and cooperate in virtually every aspect of their joint lives. This includes foraging and, on occasion, hunting cooperatively to bring down larger prey. In East Africa, jackals are renowned for a tendency to target Thomson’s gazelle fawns. One member of the duo (or small family) will fend off the spirited defence of the mother while the other lunges for the fawn. There is even anecdotal evidence of jackals using a “fascination display” to lure prey or distract larger predators from their meals. They lie down and squirm comically, attracting curious prey close enough to grab or infuriating a predator to the point that it temporarily forsakes its kill, only for the jackal to leap up and snatch a bite.

The breeding pair will also join forces to defend territories against other jackals, and observational research shows that the death of one partner has dire consequences for the survivor, usually involving the loss of territory and subsequent displacement. Territorial boundaries are ignored when a large carcass is present, and not even the pair’s combined efforts are sufficient to deter trespassers.

Wildlife corridors – paths of connection and hope

Wildlife corridors – paths of connection and hope

A successful couple will raise several litters of puppies throughout their lives, some of which will stay on to help their parents with the subsequent litter before dispersing. The pups are born in a den, which is usually an abandoned aardvark or warthog tunnel, but the female may excavate the tunnel herself. She remains with the helpless pups for up to three weeks or longer until they emerge above ground on wobbly legs. During this time, the male and any older offspring will forage for her and regurgitate food upon their return. As the pups grow and begin to explore, she will join forces with the rest of her family to provide for their voracious appetites.

All family members will bravely defend the pups against predators several times their size, snapping and snarling at hyenas or dashing in front of lions to draw them away from the vulnerable puppies. Naturally, this means that having older offspring “helpers” has a direct bearing on pup survival, particularly for larger litters. The tiny pups rapidly transform from cuddly fluffballs to competent predators, and they are already able to hunt for themselves (albeit somewhat unsuccessfully at times) at six months old. They remain with their parents for another two months, after which most will disperse, but some will stay behind as helpers. Research shows that the dominance hierarchy between siblings, particularly pronounced in black-backed jackals, may well play a role in determining which individuals decide to stick around.

A WOLF IN JACKAL’S CLOTHING

In 2015, the scientific community was rocked (well, relatively) by the revelation that Africa was, in fact, home to two jackal species, not three as previously believed. The third member – now known as the African wolf – had diverged from the Asian golden jackals well over a million years ago. Later research revealed that it is a genetically admixed canid with both grey and Ethiopian wolf ancestors. The African wolf (Canis lupaster) looks and behaves exactly like a jackal, showing how classification based on morphology or behaviour alone can be distinctly deceptive.

Advancements in genetic analysis have contributed significantly to the reclassification of many supposedly related species across several prominent mammal families, including the canids. DNA analysis from several studies shows that both the black-backed and side-striped jackals are the basal members of the wolf-like clade. In other words, they diverged very early on and are genetically distinct from the other members like the wolf and coyote (and domestic dog). As such, the IUCN Canid Specialist Group recently recommended that their scientific genus be designated as Lupulella, rather than Canis. The recommended scientific name for the black-backed jackal is Lupulella mesomelas, while that of the side-striped jackal is Lupulella adusta.

JACKALS AND PEOPLE

Since the jackal-headed Anubis (okay, so technically, he was an African wolf) first weighed the hearts of the dead, and possibly long before, jackals have played a role in the mythology of many different cultures. In many, they are the bad guy, a cunning trickster, or a sorcerer capable of shape-shifting. In Khoikhoi legends, many of the stories involve the jackal outwitting or betraying the lion. Some of these beliefs persist today, and jackal body parts and pelts are used in traditional medicine by tribes throughout Africa.

Today, however, their biggest threat comes from conflict with farmers, especially those with smaller livestock animals – as jackals will readily hunt lambs. For several centuries, jackals were seen as vermin, and various lethal methods were employed to rid the farms of their presence. Yet, as bigger wildlife species were gradually eradicated from farmlands throughout history, jackals remained, despite being killed in large numbers. Fortunately, today, educational programmes have begun to change attitudes towards the jackals and non-lethal (and more effective) techniques such as guard dogs are used to ensure livestock safety. Despite being persecuted for centuries, jackal numbers are believed to be stable and healthy populations persist across most of their natural range.