That South Africa’s young adults have it harder today than in the past is indisputable. Yet the same is often said about millennials and generation Z in the rich world. How true is this?

A great many of South Africa’s young adults find themselves in awful socio-economic straits.

To consider just one measure, the proportion of people aged 15 to 34 that were not in employment, education, or training (NEET) was 45% in the second quarter of 2022. Of the unemployed, more than half do not have a matric. Only 10% have a tertiary qualification of some description. Millions remain mired in crime-infested townships and shantytowns.

The seismic shift of the transition to democracy makes the living conditions of different generations hard to compare over time. However, complaining that today’s youth and young adults have a hard time of it is certainly justified in South Africa.

It is clear, moreover, that these hard times were brought on by a combination of socialist economic policies, mismanagement of key state institutions and state-owned enterprises, and endemic corruption.

One could therefore make the argument that a sea change in political accountability, civil service competence, and economic policies – in particular the political victory of classical liberal ideas – would reverse the trend and improve living conditions for today’s generations.

Rich world

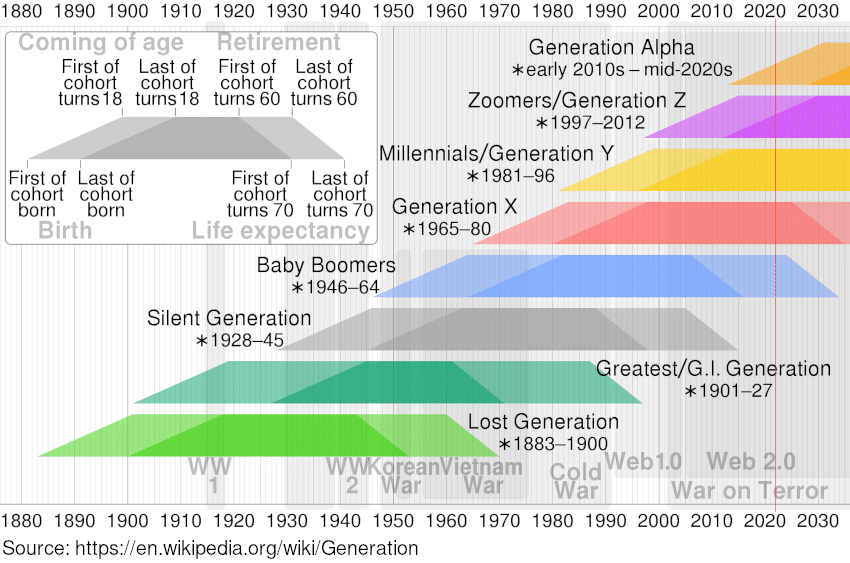

In the broadly liberal, capitalist rich world, the sentiment appears to be similar, however. There’s an endless stream of whining about how the poor millennials (generation Y) and zoomers (generation Z) can’t afford any nice things and have it so much worse than their parents and grandparents did.

‘Many millennials are worse off than their parents – a first in American history’, grumbled Tami Luhby for CNN in 2020, opening with an anecdote about a guy who earns more in real terms than his dad did at the same age.

‘Gen Zers and millennials are paying nearly 100% more for their homes than baby boomers did in their twenties,’ complained the research team of the private online advice bureau Consumer Affairs two months ago.

‘Young workers joining the labour market often do so with tens of thousands of pounds of student debt, and will struggle to find the sort of permanent well-paid, pensionable job that their parents would have walked into three or four decades ago. They have little prospect of buying a home and if they work in London will be sharing a flat with some mates in one of the less desirable districts of the capital,’ lamented Larry Elliott, economics editor of The Guardian in 2016, warning that we should no longer expect each generation to be better off than their parents.

He doesn’t spell it out, but his analysis is standard anti-capitalist class warfare stuff, pitching the ‘older and better off’ against the ‘younger and poorer’, and blaming the market for the presumed tragedy that a generation is growing up renting, rather than owning, their homes.

In a dog-whistle to his socialist comrades-in-arms, Elliott, the author of, among others, the wordily-titled book The Gods that Failed: How Blind Faith in Markets has Cost us Our Future, wrote: ‘The big unanswered question is whether this sort of economic model is sustainable, because at present it is hard to see how it will be.’ (My emphasis.)

Worse off?

Of course, the superficial complaint is entirely valid. Housing has become extremely expensive in real terms. (In fact, yet another major correction is looming in the global housing market.)

So have other goods and services, such as new cars, education, and medical care. Concurrently, the nature of work has changed. Young adults cannot expect a cradle-to-grave career with a single company, slaving away for 50 years to earn periodic promotions and a gold watch upon retirement.

That modern generations are unlikely to be able to afford a nice suburban home with a white picket fence, with a muscle car and a station wagon in the driveway, 2.4 children and a family dog, by the time they’re 30, all on a single income, is not disputable.

The question is what really caused some of these changes, and whether this really makes them as badly off compared to previous generations as they appear.

Education

First, let’s look at the causes. Elliott will blame free markets, but almost all of the things that have become more expensive have done so because of government intervention.

College tuition in the United States, for example, looks like a free market, but it isn’t. Fully 90% of all student loans in the US are issued by the federal government.

The free-market calculation for whether to embark on a degree course is whether your subsequent expected earnings will provide a return on the time and money you invested.

That calculation is thrown out the window when low-interest taxpayer money is just lying around waiting to fund four years of beer pong, protests and spring breaks. The consequence is that a lot of people enroll for degree courses that they cannot afford.

Saving the planet for future generations

Saving the planet for future generations

They make poor subject choices and discover to their great surprise that the world doesn’t really need all that many critical theorists or art historians or philosophy majors or fashion designers.

A list of the twenty most useless degree courses even includes computer science. (My own father told me studying computer science would leave me unemployable, and here I am, a freelance journalist.)

Hardly employable

All these people who graduate with useless degrees find themselves hardly employable, either because there are too many people competing for too few jobs, or because the degree didn’t prepare them to do anything marketable at all.

So, they’re stuck in low-end jobs with no way to repay their student debt. They can work their way up, of course, like non-graduates do, but then they discover something they probably didn’t learn in the humanities faculty: compound interest on unpaid debt will totally ruin you.

Then a left-leaning government forgives some of that debt, because it’s all just such an injustice!, but that only means people who did pursue useful degrees and are earning high salaries as a result, pick up the tab for the drifters, the directionless and the deluded.

Meanwhile, colleges and universities compete hard to hoover up as much of the government’s low-interest student loan largesse as possible. Billions – trillions – are on the table, and everyone wants a piece of it.

That means they’ll raise their prices. After all, their customers aren’t paying. Not now, at any rate. And they heavily market to prospective students, grabbing even those that ought to do a short programming course and get to work being useful, or start a business instead of going into debt studying entrepreneurship for four years first.

Housing

A similar story plays out in housing. Houses are assets. They are income-earning assets. When the government increases the money supply, supposedly to combat economic downturns and ‘stimulate’ the economy, that money for the most part enters the top of the financial pyramid. From there, it goes directly into assets such as stocks, bonds and… you guessed it, property.

Throw in lucrative government incentives to extend mortgages to buyers with dubious ability to afford them, and you have all the makings of a bubble.

As asset prices rise, more wealthy investors pile in, driving prices up even further. Eventually, the bubble bursts, but although such corrections are painful, they wipe out only the financially weak. The longer-term asset price trend remains positive, because the long-term monetary inflation trend remains positive.

Libertarian former US congressman Ron Paul explained all this with exquisite foresight as early as 2001, but nobody listened.

Monetary inflation

Asset prices create a buffer between monetary inflation and consumer price inflation, but inflate the money supply enough, which the pandemic response did, and all that money spills over into consumer prices, too.

When more currency is chasing the same amount of goods and services, it stands to reason that prices will rise. So, the cost of living goes up.

Although that looks a lot like greedy capitalists exploiting the poor and vulnerable, the true cause is almost entirely attributable to government intervention, and not the free markets that left-wing economic journalists like Elliott would like to blame.

Education, housing, and healthcare are some of the least free markets in the world, yet capitalism’s critics inevitably point to them as evidence that capitalism is failing.

None of them point to technology, for example, where real prices have been falling and products have been improving at breakneck speeds, thanks to free-market capitalism.

Working life

Besides blaming deliberate government policies for the rising cost of modern living, however, there’s a deeper observation to be made about the quality-of-life today’s money buys.

The transition from fixed long-term careers to job-hopping and short-term contracts does make employment less secure, but it has also been a boon to many, both directly and indirectly.

It has made companies far more efficient, which reflects in higher quality, lower prices, and improved responsiveness to consumer demands.

It has made many careers far more rewarding, too. Being able to change jobs every few years gives people a more varied experience and better opportunities raise their incomes and benefits.

Even in the gig economy, work has become more flexible, giving workers more freedom to arrange their jobs around the other demands of life.

Sure, many low-end jobs are pure drudgery, but compare that to, say, 50 years ago. Most people, especially in the silent and baby boom generations, were employed as low-level paper pushers. They were clerks and typists and low-level managers and personal assistants in very tall corporate hierarchies.

Their dull and dreary lives, and the wearisome bureaucracies they created, were the fuel for many a sci-fi dystopia, perhaps most brilliantly depicted in Terry Gilliam’s masterpiece, Brazil.

Quality

Modern generations also enjoy products and services of a far higher quality than their parents and grandparents had access to.

Modern cars, even inexpensive ones, have safety and comfort features that older generations could only dream of. Old cars had no crumple zones, no seatbelts, no airbags, no ABS braking, no electric windows, no air-conditioning, and no quiet, computer-controlled, low-pollution engines. They were uncomfortable death traps that broke often and rusted fast.

Today’s houses and apartments, likewise, are far better built and appointed than those of yesteryear. They are better constructed, better insulated, better air-conditioned, with better wiring, better plumbing, better kitchens, and better appliances than any house your grandfather might have bought.

In many ways, it is also better to rent than to own a home. Homeowners are responsible for upkeep and maintenance, which can be enormously taxing. Renters can relocate much more easily, don’t have to worry about structural maintenance, and when interest rates are higher, spend less on their housing than mortgage-owners do.

Elliott believes a generation of renters means that quality of life has gone down, but that this is really so is far from clear.

Medical care, likewise, might be more expensive, but it is also far superior to the state-of-the-art half a century ago. Today, doctors are doing MRI scans, performing non-invasive surgery, transplanting hearts, saving premature babies, and curing cancer. That, surely, is worth paying for?

Even in the shops, the variety and quality of goods available, from all over the world, and the convenience of shopping, would astonish a time-traveller from the 1960s.

Technology

Two generations ago, there were no mobile phones. Home computers were just coming out, were extremely basic, and lacked any form of network communication. Office terminals were small green screens with clacky keyboards, talking to mainframes that occupied entire climate-controlled floors.

If you wanted to know what the poverty rate of Americans in 1967 was, you’d have to go to a library and comb through printed journals. Today, it’s only a little google-fu away.

If you wanted to know what Ron Paul said 21 years ago, you’d have to know exactly when he said it, and request that a Congressional transcript from an archive be sent to you by mail. Today, you can watch him at the click of a button.

If you wanted to write a letter, you’d write it longhand, or on a typewriter, put it in an envelope, put a stamp on it, and take it to the post office for delivery in a week or so. If you wanted to talk to family overseas, you’d pay enormous per-minute rates on a crackly, analogue, fixed telephone line. If you wanted to send a message somewhere rapidly, you’d send a telegram, at significant expense.

If you needed to go somewhere, you’d consult a map book. If you wanted to be paid, they’d write you a cheque, which you took to a bank and hoped it didn’t bounce.

Today, young adults have literal supercomputers in their pockets, with instant access to global communication and a large part of the world’s total knowledge and entertainment at their fingertips.

This gives them vastly more free time than previous generations had, just because everything was such a bureaucratic hassle, back then.

They use this extraordinary technology to order fast food for home delivery, and control their interior lights, and play minecraft, and watch funny cat videos, all while complaining how hard life is.

Perspective

The two post-war decades in the United States are often viewed as a sort of golden age. That country lost fewer of its young and able-bodied men than most others and sustained almost no war damage. But even that post-war boom hardly compares to the quality of life we live today.

America’s real GDP per person, expressed in current dollars, was $3 000 in 1960. In 2022, it is $69 000. That is a 23-fold increase in just over 60 years. The US poverty rate halved between 1967 and 2020. In many other liberal democracies, the improvements have been even greater.

The silent generation and baby boomers are ten times more likely to have served in a shooting war than millennials or zoomers, and they did so involuntarily.

From a distance, the apparent stability and prosperity of the baby boom era might look appealing. But give anyone from today in a 1950s job (if male, or a housewife role if female) with a 1950s house, a 1950s car and 1950s healthcare, and they will soon rebel, become hippies, drop acid, drop out, invent heavy metal and punk and third stream jazz, and write dystopian sci-fi, waiting for Maggie Thatcher to give them the kick in the butt they need.

The world has changed in many ways. In some ways, this has created new stressors and legitimate discontent. Much of that stress and unhappiness is attributable to government policies and interventions, however.

In most ways, the world has changed for the better.

Describing the living conditions of younger generations as worse than those of older generations is a gross over-simplification and ignores the myriad ways in which quality of life has objectively improved for them.