On Saturday, 8 January 2022, the African National Congress (ANC) will celebrate its 110th anniversary.

The occasion will be marked with the release of the January 8 Statement, which outlines the party’s plans for the year. This is the most critical period in the life of this glorious movement, as it grapples with a myriad of challenges, both as a political formation and as the governing party in a democratic South Africa.

Those who have not internalised the historical vision and mission of the ANC may think it is an opportunity to use the internal challenges of the ANC, such as non-payment of staff salaries, poor performance in the recent local government elections, and the rising youth unemployment as the basis for removing and replacing the current leadership of the ANC. It is no secret that corrupt and criminal elements have sought to use every opportunity they can to mount a frontal attack on the current leadership.

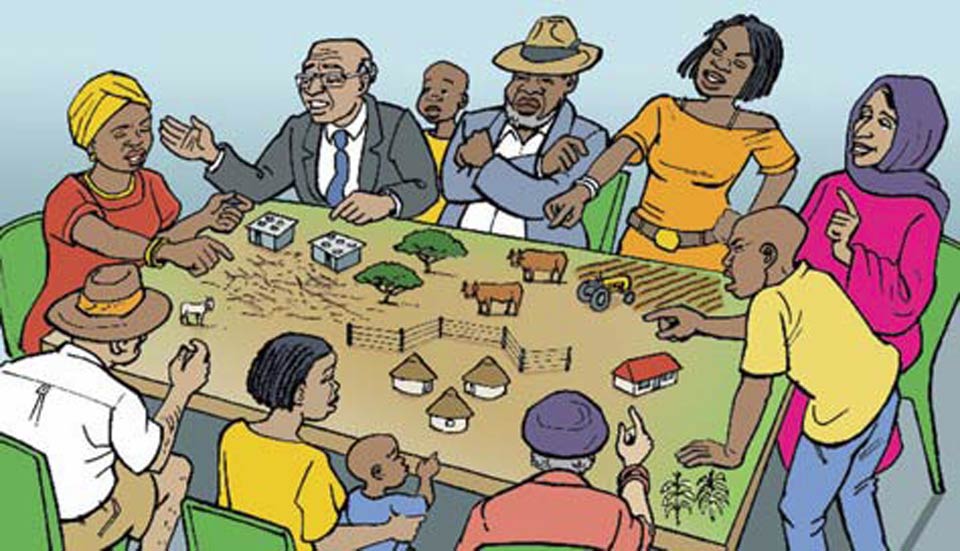

What has become evident, in the midst of all these, is that the greatest challenge facing the ANC today is no longer its unity and renewal, because this has largely been interpreted to mean the reconciliation of ethical leadership values with corruption tendencies for the sake of peace and stability of the political party. This is a false premise because the ANC does not exist for itself and for its own self-preservation. What we have seen in recent years since post-liberation South Africa is the emergence, or the coalescence of disgraced individuals and rogue elements within the ANC’s ranks intent on undermining the current administration, under the guise of so-called radical economic transformation (RET). This is against the values of the party, which has earned its position as the leader of society, guided by the principle of always putting people first and involving the masses in the development of key policy positions.

A common issue that these forces have often used to gain political traction is the ANC’s approach in addressing the land question. Yes, the ANC leadership acknowledges that this has not been an easy matter to deal with. However, an unholy coalition between the self-proclaimed RET forces and right-wing parties whose leaders are the beneficiaries of British and apartheid colonial forces and their missionaries’ allies has left the ANC frustrated in its efforts to address the matter. This was evident in the recent failure to adopt the Constitution Eighteenth Amendment Bill, which is meant to amend section 25 in order to allow the state to expropriate land without compensation.

S25 constitutional amendment sinks amid party political insults – now all eyes on Expropriation Bill

S25 constitutional amendment sinks amid party political insults – now all eyes on Expropriation Bill

The ANC remains firm that if South Africa’s enduring problem of social and economic inequality is to be addressed, the land question must be dealt with — judiciously and expeditiously. It is common cause that the country’s socio-economic problems are firmly rooted in the land question, from the time when the ‘original sin’ was committed in the early 18 century. However, there seems to be a lack of understanding of why and how the original sin was committed — when the British and Dutch settlers and their missionary allies violently dispossessed Africans of their land and its natural resources — and the gravity of the impact of this on black South Africans.

How the land was lost

It is well known that indigenous African people owned and occupied the total surface of South Africa when the British and Dutch settlers arrived during the 17th and 18th centuries. These European settlers and their missionary allies required land, natural resources and cheap labour. The liberal policies of the British Imperial power and, in particular, the abolition of slavery at the Cape forced the Dutch settlers to migrate from the Cape Colony to Natal, Free State and Transvaal in search of land, natural resources and cheap labour.

The Dutch settlers left the Cape Colony during the first half of the 1800s. When they entered Natal, Free State and Transvaal, African monarchs owned the land and were fully in charge of the administration of their own affairs. During the first Anglo-Boer War (South African War) between 1880 and 1881, African people supported the British Imperial power against the Dutch settlers, hoping that in the event of victory there would be restitution of the land and its natural resources to African monarchs ad their people and that their sovereignty would also be restored. The British lost the war but reconciled with the Dutch settlers at the expense of the African people.

During the second Anglo-Boer War (1899 – 1902), the British Imperial power urged Africans to support the British who were purportedly fighting the war for the restitution of the land and its natural resources to African people. During this war, Africans turned the balance of power in favour of the British who won the war. However, the British once again betrayed the African people, after using them as cannon fodder. They concluded the treaty of Vereeniging with the Dutch. This Treaty reconciled the British and Dutch by institutionalising the colour bar.

The critical question facing the British and Dutch settlers was therefore the native question. This question had two legs, namely, the Land Question and Native administration. The collaboration of the British and Dutch settlers after the Anglo-Boer war enabled them to address the Native Question jointly. The first step was taken by Lord Alfred Milner who appointed the South African Native Commission (SANC), which was chaired by Sir Godfrey Lagden. This commission was tasked to investigate the territorial segregation between black and white people. The SANC (1903 – 1905) allowed the British and Dutch settlers to consolidate and entrench their violent dispossession of the land and natural resources of African people and to pave the way for the creation of the whites-only Union of South Africa which was ratified by the British Imperial parliament.

The illegitimately constituted Union of South Africa’s Parliament passed the Natives Land Act (no 27 of 1913). This Act consolidated the violent dispossession of 93% of African land and its natural resources which left Africans with only 7% of the total surface of South Africa. The South African monarchs who were defeated and violently dispossessed of land and natural resources at the end of the 19th century suffered grave historical injustices. It is for these reasons that the 1996 constitution of the Republic of South Africa calls on us to address the injustices of the past.

The Struggle for land and the soul of South Africa must continue

While the ANC’s inability to garner sufficient support for the amendment of Section 25 of the Constitution is a setback, the party’s position remains the same: expropriation of land without compensation remains the only viable solution to address the land question in South Africa. It epitomises the struggle for the soul of South Africa and the quest for justice. As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o wrote many years ago, “Any man who had land was considered rich. If a man had plenty of money, many motor cars, but no land, he could never be counted as rich. A man who went with tattered clothes but had at least an acre of red earth, was better off than the man with money.”

Only righteous people can understand the national imperative of land restitution, because the greatest injustice of the past was and remains the violent dispossession of the land and natural resources of the African people. Only honest and principled people understand that the deep spiritual and religious character of African people allowed them to recognise the British and Dutch settlers as South African citizens. It is for these reasons that the 1955 Freedom Charter asserted that South Africa belong to all who live in it and that no government can claim authority unless it is based on the will of the people. This strategic concession was important to win the hostile European imperialist powers to the African side in the struggle against apartheid colonialism. This led to the 1913 compromise sponsored by the World Bank which endorsed the violent dispossession of African land and its natural resources.

Land restitution is therefore a national imperative that must be pursued until justice is served. After all, the constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108 of 1996) calls upon us to address the injustices and heal the divisions of the past. The unholy coalition of the right wing and self-proclaimed left-wing forces to gang up against the constitutional amendment which sought to return the land to its rightful African owners will not allow us to predetermine the rise or fall of South Africa. Indeed, the battle lines in this struggle have been drawn.

While it is only reasonable that the overwhelming majority of South Africans, especially the women and youth, are angry with the ANC old guard and threaten to vote them out of office, this must not blind us from seeing the hypocrisy of some forces to exploit the issue for political gain. The ANC is and remains the only sure means to bring about the desired social and economic transformation of South Africa. To achieve this, African women and the youth must continue to support the ANC in its efforts to cleanse itself of corrupt and criminal elements and enable it to pass the 18th constitutional Amendment Bill. This will empower the ANC government to return the land and its natural resources to the indigenous African people.

Now is the time for all patriotic South Africans to stand up against the anarchy that the destructive coalition of the right wing and self-proclaimed left-wing forces are bringing to our country. All peace-loving and progressive South Africans must come together and put aside their differences in defence of the soul of their motherland. If you added the letter D to the unjustified anger of the DA and the EFF towards the ANC, you will find Danger (D + anger) which will destroy South Africa once and for all. Stand up and save the soul of South Africa against the unholy alliance. This Save South Africa campaign is the surest means to guarantee the future of your children.

Mathole Motshekga