The world population is still growing, and people are getting richer. That means more energy. Sounds like bad news for the energy transition: we won’t just need to replace existing fossil fuels, we’ll need to keep up with growing demand too.

But what if, in 2050, we need less energy than we currently do? That’s a real possibility. Not because the world will get poorer, or the population will shrink. But because a decarbonised energy system needs less energy than one running on fossil fuels.

In a previous post, I covered a paper by Nick Eyre at Oxford University who estimated that decarbonisation could reduce final energy demand by 40%.

The key caveat to that paper was that it was looking at global energy demand today. It didn’t account for rising demand from economic and population growth.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) does, albeit quite crudely. I dug into the numbers to see what story it tells.

Final energy use falls with increased decarbonisation

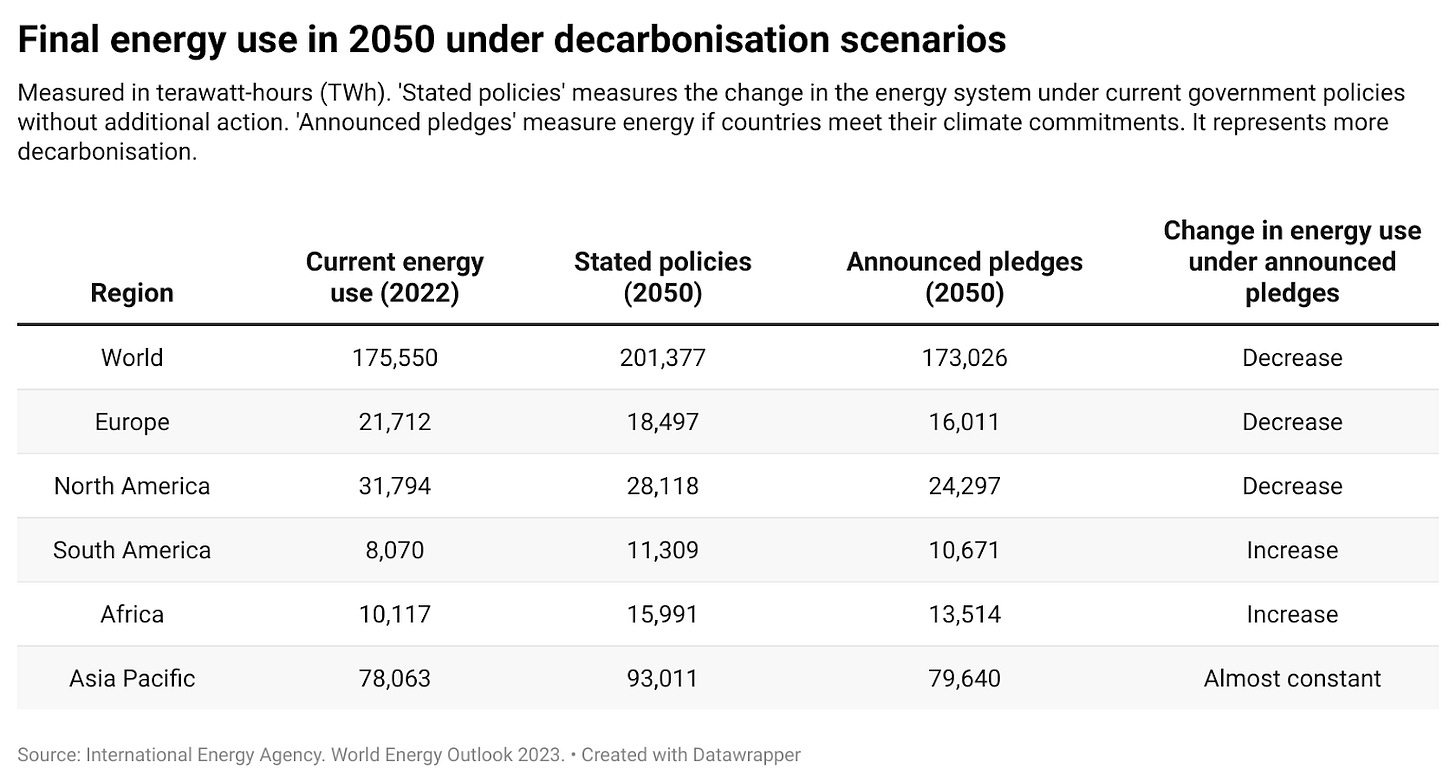

In its World Energy Outlook reports, the IEA projects energy demand in two scenarios to 2050.1

One, called the ‘Stated policies’ projects how energy systems will change under current policies in place, without any further commitments. In other words, weak decarbonisation.

Second, the ‘Announced pledges’ which assume that governments will meet their climate commitments. This is much stronger decarbonisation.

Projections of population and economic growth – and the impacts on energy demand – are taken into account.2

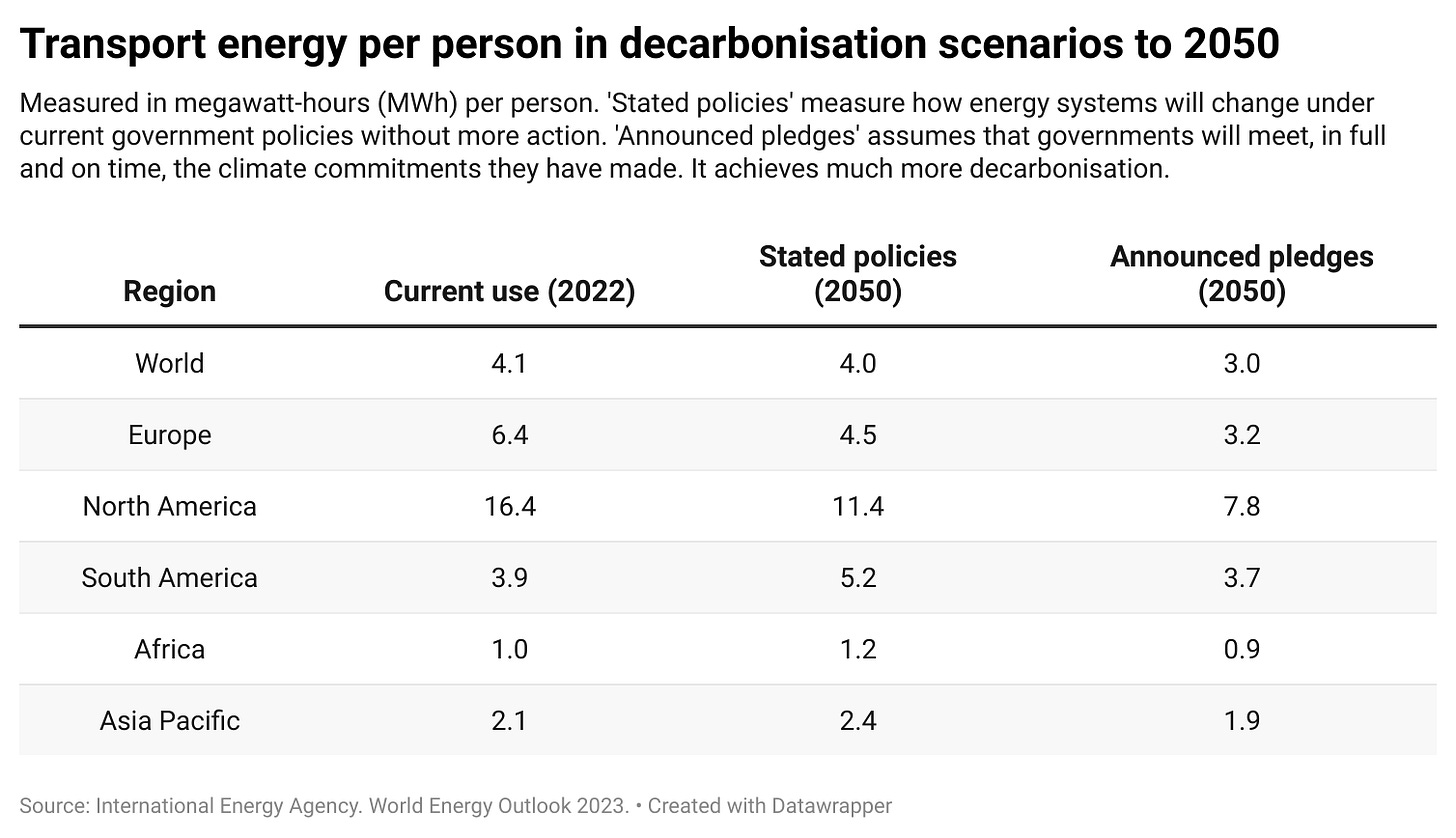

In the table, I’ve shown how it expects final energy demand to change from 2022 levels to 2050 under the two scenarios. This comes from its 2023 Outlook.

With weak decarbonisation (stated policies) global energy demand continues to rise. With strong decarbonisation, energy demand will fall slightly.

You can see large drops in demand across Europe and North America, especially with strong decarbonisation. This is because it’s electrifying transport, heating and other sectors which is much more efficient (more on this later).

In other regions, demand increases due to population and rising incomes, but much less so in the low-carbon scenario.

Importantly, this is about final energy demand. It doesn’t include the decline in primary energy demand that we’d expect with decarbonisation. This would be substantial because most energy from burning fossil fuels is wasted when converting it to final energy.

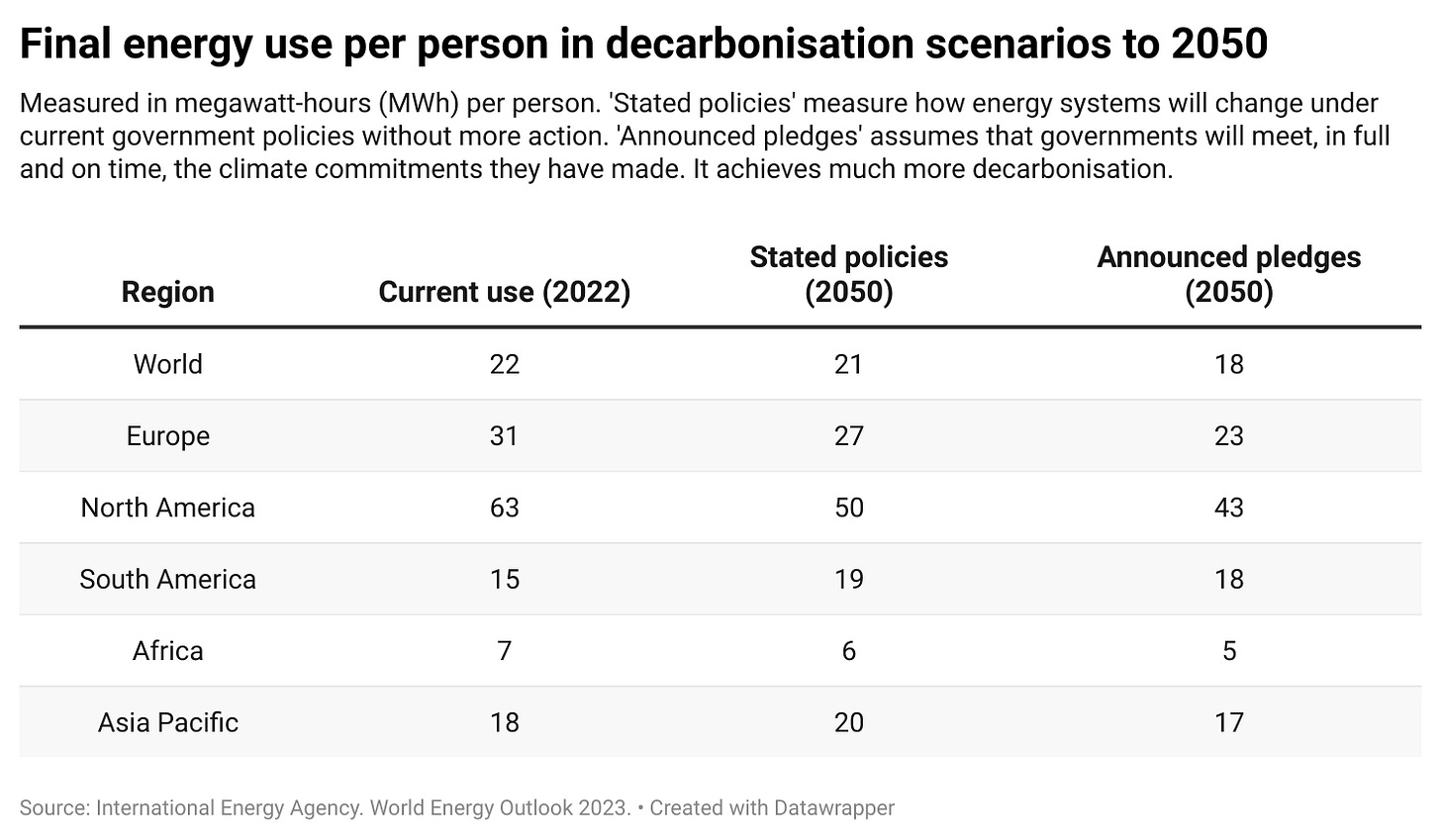

Final energy use per person will fall in most regions

What does this mean for energy demand per person?

The chart below shows this data corrected for population across the scenarios.

Global demand per person will fall, especially with more decarbonisation. We also see large drops in Europe and North America.

The reductions in other regions are more marginal (they increase in South America) due to rising incomes and living standards.

Notice the large inequalities in energy use across the world, even in 2050 (more on this later).

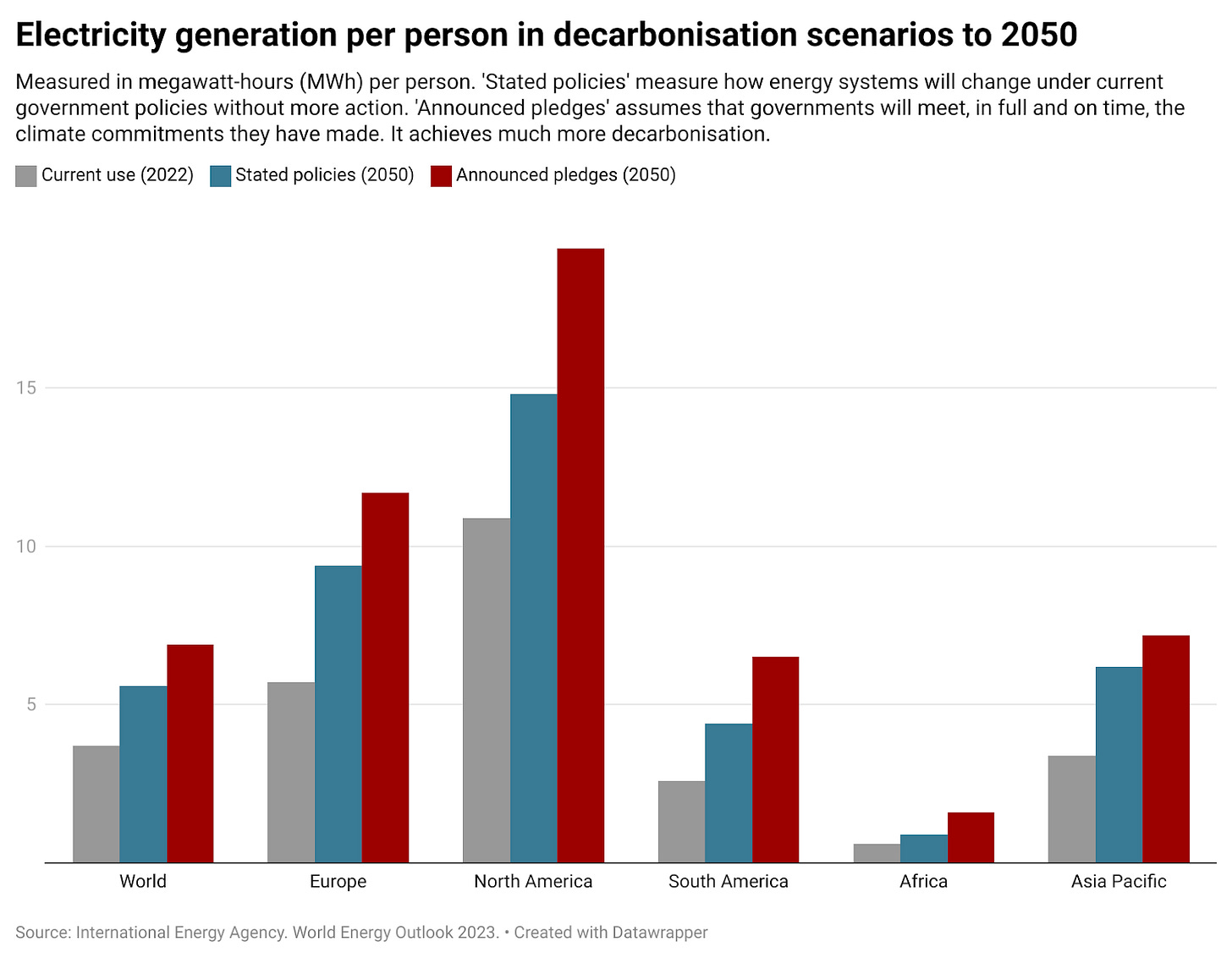

Electricity demand will increase as transport and heating are electrified

Energy demand will fall, but electricity demand will increase a lot. That’s because we’ll move from gasoline to electric cars and gas boilers to electric heat pumps.

Electricity demand per person are likely to double or triple. Again, more decarbonisation means more electricity but less final energy, and a lot less primary energy.

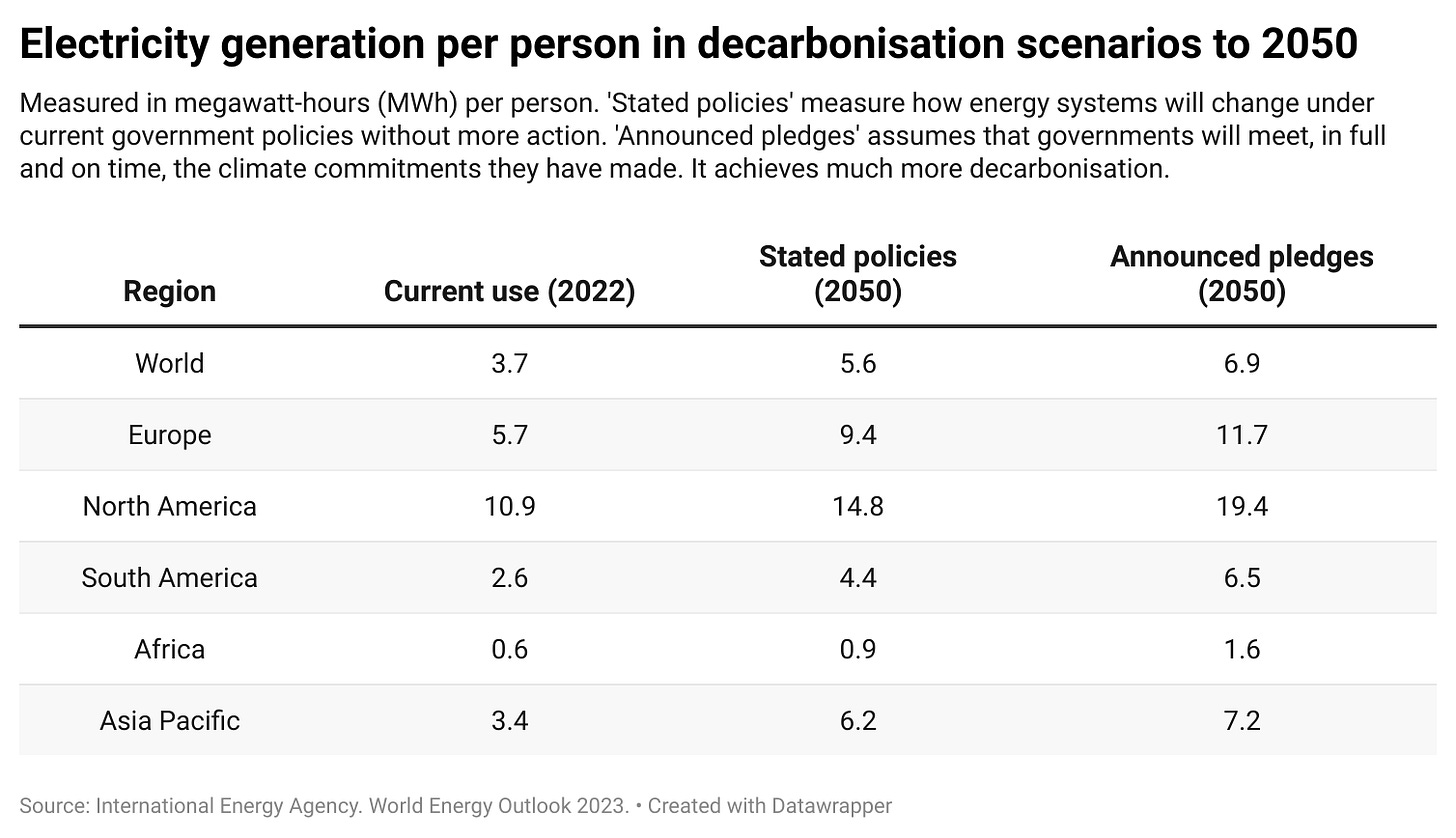

Now, for what is perhaps the most depressing figure that the International Energy Agency (IEA) publishes. In the table, I’ve shown the electricity generation per person in 2022, compared to projected figures for the two 2050 scenarios.

As expected, it increases in all regions.

What does South Africa’s energy crisis mean for food production?

What does South Africa’s energy crisis mean for food production?

But look at Africa. In the Stated Policies scenario, this increases to just 0.9 MWh per person. That’s equal to levels in Asia in 1993, when I was born. In the ‘ambitious’ Announced Pledges scenario, it’s still just 1.6 MWh. That’s Asian levels in 2005.

In short: countries across Africa will still be in deep energy (and therefore monetary) poverty decades from now. I think this point – if the IEA’s forecast is right – is just as worrying as climate change. Not least because energy access and higher standards of living protect countries from the impacts of climate change. Without it, Africa will be very vulnerable to extremes.

Most of us already have our eyes on the need for decarbonisation. We should be focusing on alleviating energy poverty just as much.

Electrification reduces demand, especially in sectors like transport

Energy demand doesn’t fall because people get poorer or living standards drop. It’s because electrification leads to large efficiency gains. This is perhaps most obvious in transport. See the large drops in transport energy demand in Europe and North America below.

Driving the same distance in an electric car needs 3 to 4 times less energy than a petrol one.

Yet the IEA projects that energy demand for passenger cars ‘only’ falls by 40% by 2050. Why?

First, it expects that there will still be some gasoline cars on the road in 2050.

But importantly, it expects that the world will drive more: rising from 27 to 45 trillion passenger-kilometres.

That’s still pretty staggering. Energy for cars will fall significantly despite the kilometres driven increasing by 70%.

Of course, there is very good reason and scope for limiting this increase in private car mileage. Investing in public transport, making cities cycle-friendly, or creating new models for car sharing and ownership can curb demand too.

In essence: simple technology change will already limit or reduce energy demand, even without changes in behaviour. But shifts in behaviour and modes of travel could help us go a lot further. Let’s figure out how to encourage and incentivise these shifts in a major way; it would offer a range of benefits beyond climate.

One of the reasons I’m most optimistic about the energy transition is that it simply makes sense from a resource and waste perspective. No one likes waste. And decarbonisation is our best opportunity to get rid of as much of it as we can.

Less waste but more ‘energy services’ for people across the world is a win-win.