Horn of Africa countries are facing some of the most severe drought conditions in decades, raising concerns that smaller harvests of principal grain crops will exacerbate food insecurity, and necessitate far higher amounts of food aid and imports.

Drought is affecting the area unevenly, however, and Gro’s newly launched Food Security Tracker for Africa, built with support from The Rockefeller Foundation, currently indicates that production of some crops will decline more sharply than for others.

For example, in Kenya, where corn is the most commonly grown crop, corn production is currently forecast to drop modestly from last year’s depressed levels. In Somalia, Gro’s forecasts show that year over year corn production will be flat, but sharply below the 10-year average. Meanwhile, in Ethiopia, sub-Saharan Africa’s largest wheat producer, wheat production is forecast to decline slightly, but it will be well above the 10-year average.

Gro’s Food Security Tracker for Africa is a first-of-its-kind, interactive tool that leverages Gro’s platform and the scaling power of our predictive machine learning-based models to show both real-time data and projections for the supply, demand, and price of major crops, including corn, soy, wheat, and rice, for 49 African countries. The Food Security Tracker for Africa is available as a free and open public tool for the next year.

The Horn of Africa’s growing season is in its early stages for wheat and for the first crops of corn, and forecasts at this stage are preliminary. As the season progresses, and changes in growing conditions alter crop prospects, Gro’s yield model forecasts become more accurate.

Unlike official government data, which often only updates once a month, Gro’s Food Security Tracker for Africa leverages our predictive machine learning-based models, which update daily and weekly, to provide real-time forecasts that reflect the impact that fluctuating weather conditions have on crop production.

Our machine-learning models use on-the-ground resources and satellite-based weather and environment inputs — including evapotranspiration, soil moisture, precipitation, land surface temperature, and other data — to produce up-to-date forecasts that can fill in the gaps.

Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia are all net importers of food, even when harvests are favorable. A drought-induced shortfall this year could greatly heighten the countries’ need for increased imports and humanitarian food aid.

The Russia-Ukraine war directly impacts the Horn of Africa region’s source of grain imports. About 40% of Ethiopia’s wheat imports, for example, normally come from the Black Sea region. The war has stalled shipments from the Black Sea and sent futures prices for wheat and corn soaring, raising costs for import-reliant countries that will likely be felt on bread prices.

Somalia

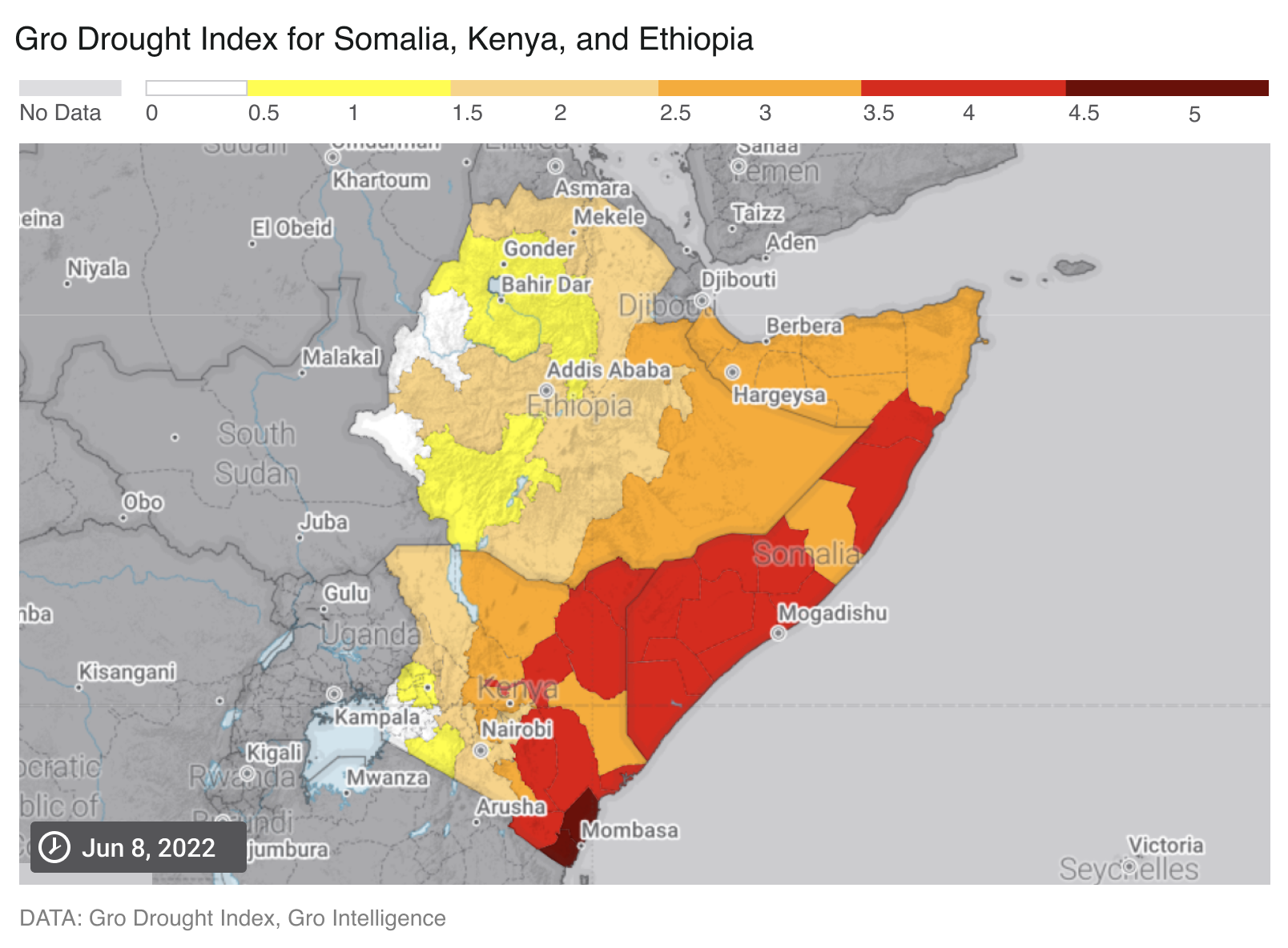

Somalia, with a population of 16 million, is experiencing one of its worst droughts in at least 20 years, hitting both pasture and field crops. In parts of the country growing corn, one of Somalia’s main cereal crops, drought conditions are at an “extreme” level, as shown by the Gro Drought Index, weighted for the country’s corn acres using Gro’s Climate Risk Navigator for Agriculture. Soil moisture levels in Somalia’s corn areas are at some of the lowest levels since at least 2010.

Gro’s Food Security Tracker for Somalia currently forecasts that the country will produce 67,000 tonnes of corn in 2022/23; this is on par with last year, but 23% below the 10-year average. As a result, corn imports will need to grow. In 2018/19, the most recent previous year of exceptional drought, Somalia imported 25,000 tonnes of corn, five times the normal amount.

The thirstland years are here – prepare for four more years of crippling drought

The thirstland years are here – prepare for four more years of crippling drought

Somalia’s first crop planting season, known as gu, has started for corn, sorghum, and millet, with harvests occurring in August. Corn is typically grown on irrigated land along the country’s largest rivers, the Shebelle and Juba. Sorghum, another major cereal crop, is more drought tolerant than corn and is grown mainly in dryland areas in the Bay region in the south-central part of the country.

A second growing season, called deyr, runs from October to April. Rains also typically occur in two cycles — “long rains” are in March-June and a shorter rainy season comes in October-February. However, crop production data is only reported annually, which can mask the sharp differences between the seasons.

Kenya

Corn is the most commonly grown crop in Kenya, and Gro’s Food Security Tracker for Kenya currently predicts a year-over-year decline of 4% in 2022/23 production, which would be 13% below Kenya’s 10-year average. Corn is grown widely throughout Kenya, and the most intense drought levels are currently in less predominant growing regions.

Kenya currently shows a drought reading of 2.91, or “severe” drought, on the Gro Drought Index, which measures drought severity on a scale from “0” (no drought) to “5” (exceptional drought). But Kenya’s most intense drought readings are in areas where less corn is grown. In Kenya’s main corn-growing regions, drought conditions are notably milder, registering 1.62, or “moderate” drought, according to the Gro Drought Index, weighted to Kenya’s corn-planted areas using Gro’s Climate Risk Navigator.

The Climate Risk Navigator for Agriculture application provides a broad range of growing conditions worldwide — also including temperature, precipitation, soil moisture, etc. — and can be weighted for multiple specific crops.

Kenya’s first corn crop is planted in March and harvested in October. That is followed by a second crop, which is harvested in March.

Corn makes up the majority of total food calories consumed by Kenyan households, and is also a major ingredient in animal feed. But Kenya is a corn deficit country, meaning it requires imports to help meet its domestic needs when production falls short. Kenya imported 700,000 tonnes of corn in 2021/22, which was more than double the previous year, due to a weak harvest. Kenya imported 1.4 million tonnes in 2017/18, the most ever recorded, after suffering the smallest crop in nearly 10 years due to heightened levels of drought.

Kenya imports agricultural commodities mainly from East African Community (EAC) countries, and normally imposes tariffs on imports from other countries. But the government announced it will temporarily waive import duties to allow corn purchases from outside the EAC amid sharply rising domestic flour prices and regional supply shortages. Kenya last allowed corn imports from outside of the EAC bloc in 2017.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, the second most populous African country, is the largest wheat producer in sub-Saharan Africa, and its production covers about 70% of domestic consumption. The rest is imported or received as food aid.

Ethiopia’s main wheat crop, currently being planted, is centered in the Oromia and Amhara regions. Rainfall in both states was slightly above the 10-year average in the critical February-April period, providing an early boost for the crop.

Gro’s Food Security Tracker for Ethiopia currently points to a 2.6% decrease in wheat production, to 5.8 million tonnes, compared with last year. The latest forecast, which follows an 11% jump in production last year, is 20% above the 10-year average. Gro’s Food Security Tracker will continue making forecasts based on growing conditions as the season progresses.

Earlier this year, drought readings declined in Ethiopia’s wheat-growing regions, but have picked up again, as shown by Gro’s Climate Risk Navigator. Soil moisture levels remain a concern and the crop will require adequate precipitation during the high rainfall months of July and August to flourish.

The Russia-Ukraine war has directly impacted Ethiopia because about 40% of its wheat imports come from the Black Sea region. The war has stalled wheat shipments from the Black Sea and sent wheat futures soaring, raising costs for import-reliant countries that will likely be felt on bread prices.

The growing season in the Horn of Africa is still in its early stages, and forecasts are highly variable. As the season progresses, view real-time updates across the continent with Gro’s Food Security Tracker for Africa.