Since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war there have been rising concerns about global food security. Both Ukraine and Russia are major agricultural producers and exporters. In 2021, these countries together accounted for nearly 30% of global wheat exports, about 14% of global maize exports, roughly 32% of global barley exports, almost 60% of global sunflower oil exports, and about 14% of global fertilizer exports.[2]

The destruction of economic infrastructure within Ukraine, combined with various shipping lines avoiding the Black Sea region and the extensive sanctions that Western countries have imposed on Moscow, mean there will be limitations on the movement of the agricultural products from these countries. This will be exacerbated by other factors, such as the agreement to exclude some Russian banks from global payment systems such as SWIFT.

Notably, the Russia-Ukraine war occurs at a time when the global agricultural commodity prices were already elevated as a result of relatively lower grains and vegetables oils stocks.[3] The drought in South America, specifically Brazil and Argentina, which together account for 14% of global maize and 50% soybean production, has already pushed up global prices for much of the past two years.

Additionally, the rising demand in China and India for soybeans and other vegetables oil, combined with poor palm oil produce in Indonesia, has added upside pressures to global vegetables oils prices. As the Russia-Ukraine war began, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Global Food Price Index averaged 141 points in February 2022, which is an all-time high, exceeding the previous peak in February 2011.[4] On a year-on-year basis, the FAO reflected an increase of 21% in February 2022.

Given these realities, it is important that we understand South Africa’s linkages to Russia and Ukraine agricultural trade, and how the unfolding war could potentially impact domestic food supplies.

SA’s agricultural trade with Russia-Ukraine

South Africa has relatively weak agricultural import ties with both Russia and Ukraine. Russia is the 17th-largest agricultural products supplier to South Africa, and Ukraine the 44th. In value terms, agricultural imports from these two countries accounted for just 2.4% of South Africa’s total agricultural imports of US$5.9 billion in 2020.The major products both countries export to South Africa are wheat and sunflower oil. Over the past five years (2016-2020), South Africa imported an average of 1,8 million tonnes of wheat per calendar year, roughly half the annual wheat consumption needs. Of this, wheat imports from Russia and Ukraine averaged 34% and 4%, respectively.

The significance of Russia in South Africa’s wheat imports basket may raise concerns about the near-term supplies. And from this perspective, in the current wheat marketing year of 2021/22 that ends in September, South Africa has already imported 40% of its estimated imports of 1,5 million tonnes. However, it will likely be able close the import gap for the remaining balance for the year from various countries such as Germany, Canada, Australia, Latvia, Argentina, and the Czech Republic, amongst others. But this will probably be at higher cost than the volumes already imported because of the upside pressure the war has added in the commodities market.

Moreover, South Africa imported an average 174 138 tonnes[5] of sunflower oil per year from the world market between 2016 and 2020. During this period, imports from Ukraine averaged 4% of the total. Bulgaria supplied 40% of South Africa’s imported sunflower oil, Romania about 22%, and Argentina 15%.

That said, these data do not minimize the importance of these countries for South Africa’s food basket. Russia and Ukraine may not be major supplies of agricultural products to South Africa, but they have strong ties with the global grains and oilseeds market given their large export share contribution and this has an important bearing on commodity prices.

This means the impact of the disruption in trade will, in the near term, be felt through prices rather than through a shortage of products. The FAO Global Food Price Index, which was already at all-time high in February, could register a new high when March 2022 results are released on 07 April 2022, and remain elevated for the months thereafter, depending on the length of the conflict and market uncertainty.

Conversely, from an export perspective, Russia is a notable market – the 13th largest. South Africa's products to Russia and Ukraine are mainly citrus, nuts, vegetables, and tobacco. Importantly, in 2020 Russia accounted for 7% of South Africa’s citrus exports in value terms, and for 12% of apples and pears exports in the same year – the country’s second largest market.

Aside from the Black Sea region, South Africa generally has stronger agricultural export ties with the African continent, Asia, the United Kingdom, and the European Union. In the third quarter of 2021, the African continent and Asia were the largest markets for South Africa's agricultural exports, accounting for 35% and 33% in value terms, respectively. The European Union was the third-largest market, taking up 23% of South Africa's agricultural exports. The balance of 9% value constitutes the Americas and other regions of the world.[6]

Dependence on imported agricultural inputs

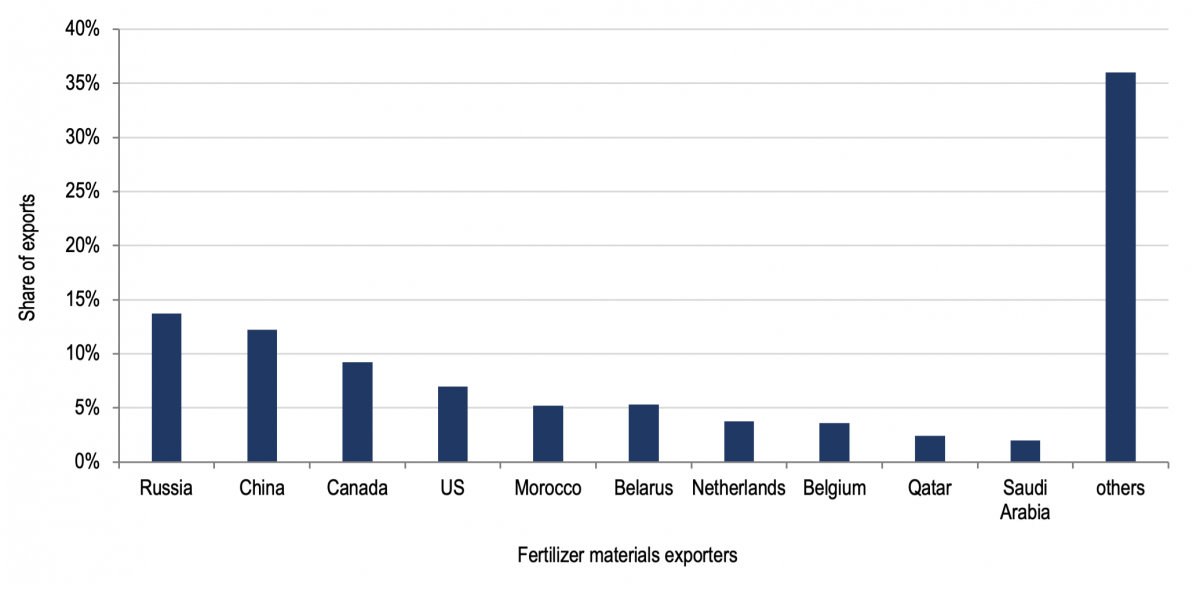

Russia is also integrated in global agriculture through inputs market, and here lies a major risk for import dependent countries such as South Africa. Russia is the world's leading exporter of fertilizer materials in value terms, followed by China, Canada, the US, Morocco, and Belarus (see Figure 1). These fertilizer mixtures include a variety of complex minerals and chemicals, including nitrogenous fertilizers, phosphoric fertilizers, and potassic fertilizers.

Figure 1: Share ranking of the world's top fertilizer exporters by value (2016 and 2020)

Source: Trade Map and Agbiz Research

Fertilizer prices increased sharply throughout 2021 and have remained elevated since the beginning of this year. For instance, in January 2022, international ammonia, urea, di-ammonium phosphate, and potassium chloride prices were up by 220%, 148%, 90%, and 198% from January 2021, respectively.[7] There are many factors behind these sharp input cost increases, such as the supply constraints in critical fertilizer-producing countries, mainly China, India, the US, Russia, and Canada. Rising shipping costs, and oil and gas prices are also contributing factors to the price increases, along with firmer global demand from growing global agriculture.

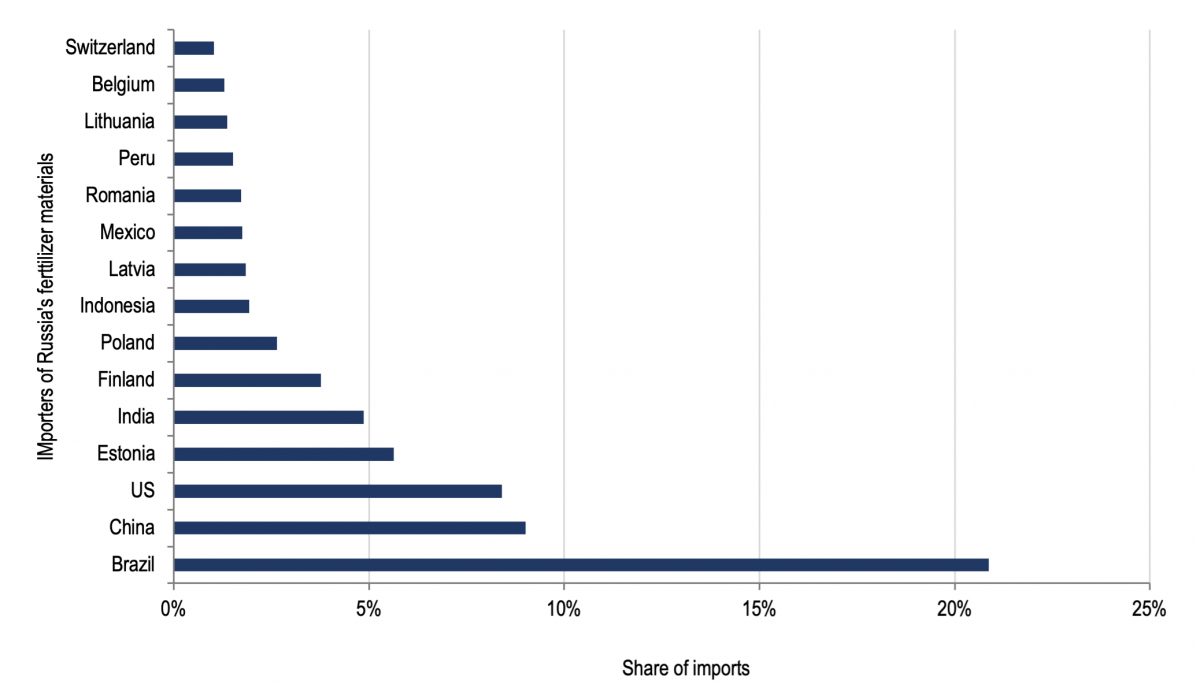

The Russia-Ukraine conflict will add upside pressure to these already higher fertilizer prices, particularly if Russia's exports suffer as a result of sanctions. The primary markets for Russia's fertilizer material are Brazil, Estonia, China, India, the US, Finland, Mexico, Poland, Romania, and Latvia, among others (see Figure 2). Still, even countries that have minimal direct fertilizer imports from Russia, such as South Africa, which is the 36th largest fertilizer materials market for Russia, will experience the price pressures from the international market.

Figure 2: Russia's top fertilizer materials markets by share between 2016 to 2020 (value)

Source: Trade Map and Agbiz Research

Unlike the US and Canada, with notable domestic fertilizer production capability, South Africa's domestic fertilizer production capacity is weak, in part, because of the lack of some input minerals. South Africa imports about 80% of its annual fertilizer needs and is a minor player globally, accounting for 0.5% of total global consumption. Therefore, local prices tend to be influenced by developments in the major producing and consuming countries, such as Russia and the other major fertilizer players mentioned above.

Much of the fertilizer imported by South Africa is utilized in maize production, accounting for roughly 41% of total consumption. The second-largest consumer is sugar-cane farming, at 18%. Fertilizer constitutes about 35% of grain farmers' input costs and a substantial share in other agricultural commodities and crops.[8] Farmers have already planted the 2021/22 summer crops with these higher input costs. They will not be procuring fertilizers until around mid-year and into the third quarter of the year when they prepare for the next season (i.e the 2022/23 production season).

Depending on the how long the Russia-Ukraine conflict continues, and the extent of the response measures such as sanctions by other countries, fertilizer prices could still be elevated when the next planting season starts.

In the near term, the winter-crop producing areas such as wheat, barley, canola and oats, among others, which have to start the new planting season at the end of April, are most exposed to higher fertilizer prices, along with a range of horticulture (vegetables and fruit) products.

How the war will affect the South African consumer

Aside from the products discussed above, South Africa is generally a net exporter of agricultural products and has sufficient supplies for domestic consumption and exports to the typical markets. Still, given the possible spike in demand for major grains such as maize, South Africa should keep a close eye on its supplies to ensure that while exports continue, the country keeps sufficient supplies for domestic use.

To be clear, this is not a call for policy intervention on the movement of crops per se. Rather, regular monitoring and publication of output and export volumes allows market pricing to adjust accordingly, as is already the usual practice for most major commodities such as grains.[9] The information about the supplies and domestic stocks will be a sufficient signal to the market, which will adjust the export volumes through price. When South Africa's stocks are stretched, the price increases will force buyers to look elsewhere, and thus ensure that there is availability of supplies in the country.

For the South African consumer, the inescapable effect will be higher prices. The rise in agricultural commodity prices, domestically and globally, along with rising fuel costs, presents significant upside risks to consumer food price inflation. However, it should be noted that farmers do not necessarily always produce food products, but rather agricultural commodities that are inputs into manufactured food. This means that the final food-products price consumers pay is a combination of a range of factors, including labour, transport, and processing.[10] This also means that an increase in commodities prices does not necessarily mean an instant rise in retail prices. There is typically a lag, especially for grain-related products, as manufacturers usually keep several months’ worth of inventories for their production processes.

Moreover, we are in an environment of increasing grains and vegetable-oil prices, but fruits and vegetables could come under pressure. With Russia, a key market for some fruits, temporarily disrupted, products that would have been exported there will remain in South Africa or diverted elsewhere. The meat price inflation dynamics are also uncertain, as some farmers could increase slaughtering on the back of higher animal feed costs (maize and soybeans). This means that the food basket products are not all increasing at the same rate, and there is possibility of moderation in some products. But with fuel being an underpinning product for movement of most food products, the risks to overall consumer food-price inflation are generally.to the upside.

At the Agricultural Business Chamber of South Africa (Agbiz), we had initially thought South Africa's consumer food-price inflation would average between 4% to 5% in 2022 (compared with 6.5% in 2021). When we made the current consumer food price inflation estimates, the war was not on our radar, even though the global food prices were already relatively high. However, we now see more upside risks to these numbers, and we are currently reviewing our forecasts, a tough exercise in the current volatile environment.

Conclusion

Much remains unknown about the coming weeks and months. But there is little doubt that local agricultural markets and consumers will be affected by these geopolitical events, primarily through the price transmission of a range of commodities and inputs.