Heleen Viljoen and Christiaan Vercueil - Technical Article - Third runner up -2022

Are producers causing food prices to rise?

Maize meal and sunflower oil are some of the most common items found in the pantry of a South African consumer. The consumer price index (CPI), which refers to a weighted average basket of consumer goods and services purchased, includes both these items. In the current economic climate, retail prices of these goods are struggling to stay reasonably priced following the Russian/Ukraine war together with production pressure for raw material producers and other international turmoil. These production pressures include steep increases in input costs, that are highly correlated with the total production cost of raw materials such as maize and sunflower. But to what extent does these production pressures influence the price that a consumer pays for household items?

The value chain for common household goods

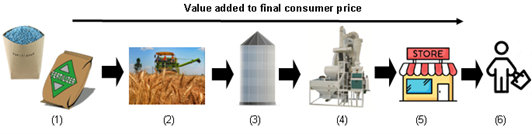

The value chain of producing a retail product from raw commodities has many links. A value chain starts off with the raw product and each link in the value chain adds value to the product until an end-consumer product is finalised. Figure 1 represents a general value chain for common household products:

Figure 1: Value chain for common household products.

The participants in the value chain flows are as follows:

- The input suppliers: The inputs suppliers include companies that supply inputs, like fertilizer, seed and agro chemicals needed to produce the raw commodities. Input price hikes have a direct impact on the cost of production a producer experiences. A producer is a price taker, therefore his ability to give through higher input prices to the rest of the value chain is limited.

- The grain producers: The grain producers form the second link of this value chain. Once the soil has been prepared and the necessary inputs have been acquired, then production can start.

- Storage facilities: Once the commodity is ready for harvest, producers transport the raw material to the nearest silo or miller. The miller then processes and refines the raw material into products as per consumer preference.

- Processors: After the raw material is refined into the respective products, the miller either distributes the products under their own brand or sells the refined product to established brands.

- Retail: The respective brands distribute the product to retailers and wholesalers.

- Costumer distribution: The retailers and wholesalers then distribute the product to the end consumer.

Each link in the value chain incurs a cost for producing their respective output product which directly leads to value added to the final retail product. Following the Russia / Ukraine conflict, global energy prices increased significantly. The war had multiple spill-over effects, especially into fuel and energy prices. The cost of production, for example a maize miller, was thus affected twofold. Millers had to pay more for the electricity to produce products, as well as pay more to transport products to specific locations. In the current environment, each link in the value chain is subjected to the energy price increases. Thus, at each value chain link, the effect of increased energy prices will end up contributing to the value added to the final product.

Effect of commodity price increases on household products

Final consumer prices follow an extensive chain of value contribution until display on retail shelves. Following the chain for a producer, SAFEX contract prices are the starting point. However, the SAFEX price producers receive can be viewed as the maximum income from which inputs costs (both variable- and fixed) are subtracted, as well as transport differentials and storage costs, amongst others.

Comparing the price (R/ton) producers receive for their commodity, with the R/ton value of key household products, the following results were found:

For a 2,5kg bag of maize meal, the producer price only contributes (on a ten-year average) 51% to the final consumer price. The derived producer price is calculated by using the average annual SAFEX price for each marketing year then deducting the relevant location differential as well as handling and storage costs. The remaining percentages are contributed by value added through the value chain, this includes packaging, processing, and milling- all of which requires energy and fuel, which had significant increase in 2022.

For a 2,5kg bag of maize meal, the producer price only contributes (on a ten-year average) 51% to the final consumer price. The derived producer price is calculated by using the average annual SAFEX price for each marketing year then deducting the relevant location differential as well as handling and storage costs. The remaining percentages are contributed by value added through the value chain, this includes packaging, processing, and milling- all of which requires energy and fuel, which had significant increase in 2022.

Figure 2: Maize producer's percentage share of the retail 2.5kg maize meal price (2021/22)

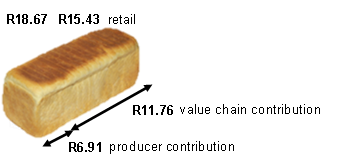

Figure 3: Sunflower- and wheat producer's percentage share of the retail sunflower oil, and bread prices (2021/22)

For a loaf of bread, the producer price only contributes (on a ten-year average) 27% to the final consumer price. For a 750ml sunflower oil, the producer price only contributes (on a ten-year average) 49% to the final consumer price. From the figures it is evident that the majority of value is contributed through the value chain. Each of these links are dependent on energy, and fuel costs to continue with operations.

Conclusion

Consumers often believe that high prices of household’s goods are contributed by commodity producers however, as shown above, is not always the case. Commodity producers are not solely responsible for the retail price of goods. Value is added by the different links in the value chain, each contributing to the final price of the product. Moreover, following the Russia/ Ukraine conflict each link in the value chain is affected by increased energy prices, which will end up contributing to the value added to the final consumer product.

Heleen Viljoen and Christiaan Vercueil

Christiaan Vercueil

Christiaan Vercueil

I grew up in Limpopo, just outside of Polokwane. My father is a potato farmer, and therefore I have always had a love for agriculture. I completed my Bcom Agribusiness management degree and afterwards my honours degree in Agricultural economics at the university of Pretoria. I have started as an intern agricultural economist at Grain SA in November 2021 and has recently been promoted to Junior economist.

Heleen Viljoen

Heleen Viljoen

I grew up in Durbanville in a household where the finance world had a strong influence. From there I went on to study Agricultural Economics at the University of the Free State, where my love for agriculture grew. I am currently a Junior economist at Grain SA where I get to combine both my love for agriculture with economics. I am also part-time busy with my Master’s degree, with a focus on the functioning of the South African commodity markets.