The 30 Largest U.S. Hydropower Plants

- Hits: 1364

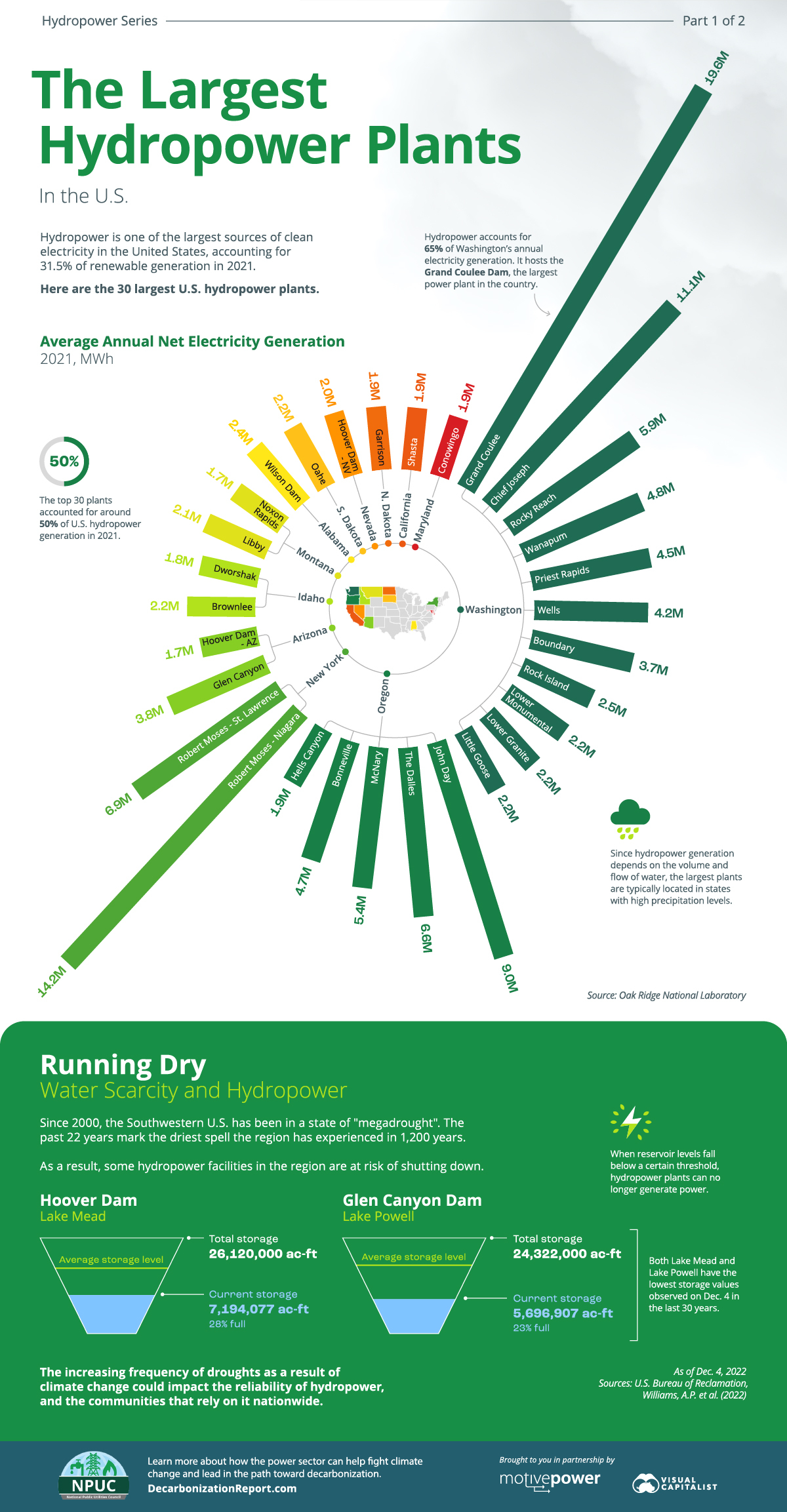

The 30 Largest Hydropower Plants in the U.S.

Did you know that the largest power plant in the United States is hydroelectric?

Hydropower is the second-largest source of U.S. renewable electricity generation and the largest source of power in seven different states.

The above infographic from the National Public Utilities Council charts the 30 largest U.S. hydropower plants and shows how droughts are starting to affect hydroelectricity. This is part one of two in the Hydropower Series.

Dam, That’s Large: U.S. Hydropower Plants by Generation

The top 30 hydropower plants account for around 50% of U.S. hydroelectric generation annually.

Hydropower plants are most prevalent in the Northwestern states of Washington and Oregon, jointly hosting 16 of the top 30 plants.

| Plant Name | State | 2021 Avg. Net Electricity Generation (MWh) | % of Total Hydropower Generation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Coulee | Washington | 19,550,777 | 7% |

| Robert Moses - Niagara | New York | 14,186,130 | 5% |

| Chief Joseph | Washington | 11,092,216 | 4% |

| John Day | Oregon | 9,041,083 | 3% |

| Robert Moses - St. Lawrence | New York | 6,906,420 | 3% |

| The Dalles | Oregon | 6,613,185 | 2% |

| Rocky Reach | Washington | 5,935,038 | 2% |

| McNary | Oregon | 5,369,726 | 2% |

| Wanapum | Washington | 4,820,651 | 2% |

| Bonneville | Oregon | 4,659,483 | 2% |

| Total | N/A | 137,135,005 | 50% |

The Grand Coulee Dam in Washington is the country’s largest power plant. It generates over 19.5 million megawatt-hours (MWh) of electricity annually and supplies it to eight states, including parts of Canada. Overall, 10 of the top 30 hydropower plants are in Washington.

The Robert Moses Power Plant is a close second, located around 5 miles downstream from Niagara Falls. Combined with the nearby Lewiston Pump Generation Plant, it is New York’s single-largest source of electricity.

While hydropower is a relatively reliable renewable power source, prolonged dry conditions can put it at risk. That is the case for both the Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams, which are no longer running at previous capacities.

Running Dry: Water Scarcity and Hydropower

The Southwestern U.S. has been in a “megadrought”—a prolonged drought lasting longer than two decades—since 2000. In fact, it has gotten so severe that the past 22 years mark the region’s driest spell in 1,200 years.

Consequently, many Southwestern reservoirs have below-average storage levels. When these levels fall below a certain threshold, hydropower plants can no longer generate power.

In particular, storage levels are precariously low at Lake Mead (Hoover Dam) and Lake Powell (Glen Canyon Dam), which supply most of Arizona’s hydroelectricity. They are also the two largest reservoirs in the country.

Here’s a look at how filled these reservoirs are as of Dec. 4, 2022:

| Reservoir | Total Storage (acre ft) | Current Storage (acre ft) | % Full |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lake Mead (Hoover Dam) |

26,120,000 | 7,194,077 | 28% |

| Lake Powell (Glen Canyon Dam) |

24,322,000 | 5,696,907 | 23% |

To put those figures into perspective, here’s an animation looking at Lake Powell’s surface area changes from 2018 to 2022:

Shrinking water levels at reservoirs threaten the reliability of hydropower and the millions of people that rely on it for electricity. As droughts become more frequent due to climate change, what does the future of hydropower look like?