Over the space of a few days, aquatic life in several Mpumalanga rivers and streams was all but wiped out after an unknown volume of contaminated water burst from the South Shaft of the old Kromdraai coal mine near Emalahleni (Witbank) on 14 February.

The mine was closed in 1966, according to the current owner, Thungela, which was demerged from the Anglo American group less than a year ago.

Quite what that means is anyone’s guess, since the exact cause of the pollution has yet to be fully explained by the company or the national Department of Water Affairs and Sanitation. What is known, however, is that at least three tonnes of dead fish (from 23 different species) were scooped up in the aftermath and buried to stop crocodiles, birds and other predators from eating the poisoned meat. Necropsy reports by the University of Pretoria showed severe damage to fish gills, along with visible tissue damage to their stomachs and intestines. In simple terms, the gills were so badly eaten away by the acid water that the fish were unable to breathe and absorb oxygen.

Hardly surprising, perhaps, considering that the acid mine drainage (AMD) plume from Kromdraai was still classified as acidic when it reached Loskop Dam — even after the dilution from travelling at least 60km via the Kromdraaispruit, Wilge and Olifants river systems.

AMD is caused by underground chemical reactions between water, oxygen and rock formations containing sulphur-rich minerals.

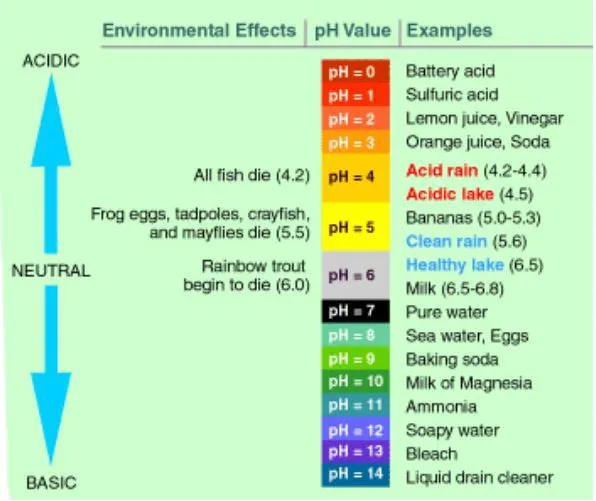

It is not clear just how acidic the water was when it left the old Kromdraai mine, but it is understood that the water was close to 2 on the pH scale along sections of the Wilge River, and around 4.5 just a few kilometres before reaching Loskop Dam.

Battery acid and sulphuric acid have a pH of 0 and the gastric juices in our stomachs have a pH of 1. Lemon juice has a pH of about 2, while vinegar is around 2.5, according to the US Geological Survey.

By the time the Kromdraai acid pulse reached the top section of Loskop Dam, the pH is believed to have changed to around 6 and was diluted rapidly to around 9 shortly after entering the massive Loskop Dam and nature reserve, where crocodiles had been all but wiped out just over a decade ago.

Reasons for the historic demise of crocodiles in Loskop and other parts of the Olifants River remain unclear, but some studies have suggested links to them eating rancid fish poisoned by acid mine drainage in the surrounding region.

To replenish this denuded population, more than 40 crocodiles were reintroduced to Loskop last year. So far, no new crocodile deaths have been reported due to the most recent AMD spill, but several of these reptiles were seen eating dead fish and there is concern for their long-term health.

Officially, there are at least 6,152 “ownerless and derelict” mines and mine dumps scattered across the country, according to a presentation to Parliament in 2010 by the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy.

Some of the massive, hidden costs of the country’s mining legacy were highlighted in a report by researcher Kerry Bobbins in 2015.

Bobbins warned that many of these mines continue to pollute the soil, air and water and that rehabilitation costs were estimated to be in excess of R30-billion.

“This wider waste legacy has profound implications for South Africa’s economy and society, and the Gauteng City Region in particular. Mining is still seen as the primary driver of the South African economy, and the benefits of mining activity are regarded as superseding any negative effects on the environment … As many mines become more marginal, and profits contract, there is little incentive to do anything more than meet the minimum requirements contained in a loose assortment of laws and regulations,” she stated.

Separate research in South Africa and other parts of the world have also focused on the lingering negative effects of abandoned mines.

90% of plastic polluting our oceans comes from just 10 rivers

90% of plastic polluting our oceans comes from just 10 rivers

One example comes from Poland, where ground subsidence of up to 1cm a day has been recorded in several parts of the Upper Silesia coalfields, along with damage to buildings, roads, railways and pipelines due to mine-induced sinkholes and subsidence.

Research shows that coal mining in Upper Silesia has caused an area of almost 600km2 to sag due to sinkholes and subsidence. In some areas, there was also evidence of surface fractures, crevices, faults and earth slides, along with changes to underground water flow.

In South Africa, the Witbank coalfield is the most important centre for current mining activity, with about 55 collieries operating there during 2009.

According to a report published in 2012 by Dr Vanessa Banks and fellow members of the British Geological Survey, past legislation did not place great emphasis on the rehabilitation of South African mining areas, so many mines simply closed and were abandoned without any rehabilitation.

“In 1975 the Fanie Botha Accord placed the responsibility for the impacts from all pre-1976 derelict and ownerless mines on the State. The first act that placed the environmental liability and responsibility of sustainable land use into mine closure planning on the mine operator was the Minerals Act (Act 50 of 1991).”

After 1994, the new Constitution forced further reform, leading to the promulgation of new mining legislation as well as the National Water Act and National Environmental Management Act. Further mining legislation passed in 2002 placed the liability for environmental and social impacts on the mine until a closure certificate has been issued by the Department of Mineral Resources.

Banks said Mpumalanga had the highest levels of acid rain in the country, while soils were also becoming progressively more acidic due to the large number of coal mines and power stations in this province.

“Mpumalanga also generates the largest amount of hazardous waste in South Africa, a third of national production. Much of the hazardous waste is produced by the industrial and mining sectors. It is important to note that less than 0.1% of this actually reaches a hazardous waste site,” according to the Banks report.

Coal mining started on the old Witbank coal seams in 1896 and for many decades mining depended on the traditional bord and pillar method which carried inherent risks of collapse over time.

“The consequences of pillar collapse are far-reaching and include: loss of agricultural land, adverse effects on land values, damage to infrastructure and property, potential for air entry to abandoned mines with the consequential potential for self-combustion and disruption of groundwater levels and flow paths. Cracks developing in the overlying strata also become conduits for water flow into the mine workings.”

A Council for Geoscience report published in 2011 also raised concerns about the risk of soil and rock subsidence above abandoned coal mines in the old Witbank coal mining seams, noting that this ground subsidence can change normal hydrological pathways.

“The ponding of water in subsidence basins results in an increase in groundwater recharge. The groundwater circulating through mining cavities becomes polluted and discharges into the natural environment contaminating wetlands, streams and dams.”

According to the national Department of Water Affairs, the owners of the Kromdraai mine have acknowledged culpability for the recent AMD spillage and department officials had served a directive on the company for its alleged failure to “take all reasonable measures to contain and minimise the effects of the incident that led to the pollution”.

“The Directive relates to Kromdraai Mine engaging in water use activities without authorisation by discharging acid mine water into the Kromdraai River following the incident of the collapse of an old shaft at Kromdraai Mine on or around 14 February 2022.”

The owners had been instructed to take all reasonable measures to contain and minimise the effects of the incident, undertake clean-up procedures and appoint a suitably qualified professional to compile a rehabilitation plan for all the affected areas.

To dilute the acid water plume, large volumes of clean water had been released from the Loskop, Wilge, Bronkhorstspruit and Middelburg dams.

“Pollution of water resources will not be tolerated, and polluters must pay for their irresponsible actions,” department spokesperson Sputnik Ratau asserted in a statement.

Thungela has reported that “an uncharacteristic environmental incident took place” at its Khwezela Colliery’s Kromdraai site and the company was treating it with “the utmost seriousness”.

“The incident took place at the South Shaft which forms part of an old mine that was last operational in 1966. The shaft had been sealed since 2019. Our initial investigations determined that a concrete seal at the shaft had failed, leading to an uncontrolled water release into the Kroomdraaispruit and travelled approximately 60km to Loskop Dam.

“The water originates from old underground workings which is acidic and rich in metal. We have a water management plan in place for post-closure water management, however, the release exceeded the capacity of the current management measures. A full investigation of the root cause of the incident and related facts is under way and will be concluded in due course,” said Thungela spokesperson Mpumi Sithole.

In response to questions from Our Burning Planet on which company (Anglo or Thungela) would bear responsibility for cleaning up the mess, Sithole said Anglo had more than halved its thermal coal production since 2015 by selling many of its mines in South Africa and elsewhere in the world.

At its annual meeting in 2020, Anglo announced that it was working to exit its South African thermal coal operations, with the preferred option of a demerger of a listed company with a primary listing on the JSE.

“This ring-fenced private company (Thungela) was demerged out of the Anglo American group in June 2021 hence the name change. A demerger is the separation of a business unit of a larger company into a separate and independent entity,” Sithole said.

“Thungela has put in place adequate resources to cater for the rehabilitation of Kromdraai. This includes financial resources for the treatment of mine-affected water from Kromdraai at the Emalahleni Water Reclamation Plant.”

But she appeared to shift some of the blame, stating that: “Due to illegal mining in the Kroomdraai area we have lost critical infrastructure estimated at R150-million connecting the area to our water treatment plant.

“Maintenance efforts are severely impacted by this criminal activity. All illegal mining activities have been reported to [the] Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) as well as the South African Police Services. To counter illegal mining and criminal activities, we have also taken legal action.”

Because cleaner raw water from local dams was used to dilute the Kromdraai pollution, affected river water quality had returned to normal.

“We have communicated this to the farming community — that the water is safe for crop irrigation and drinking for cattle and other animals… At this stage, we do not have an indication of how long it could take to rehabilitate the aquatic ecosystems. We are fully committed to continue working with authorities, the farming communities and specialist biodiversity, environmental, water and health experts to remedy the effects of the incident.”

However, independent experts told us that it could take decades to restore the ecology of the river — and this would also depend on no further pollution from mines or human sewage from dysfunctional municipal water treatment works in the region.

Annerie Weber, a Democratic Alliance MP and the party’s former provincial director in Mpumalanga, has called for a thorough investigation into the Kromdraai environmental disaster, along with immediate intervention by the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment.

“According to the Mpumalanga Parks and Tourism Agency, this is one of the biggest river ecology disasters they have experienced in the past 40 years, with 23 indigenous fish species dying during this incident … Experts estimated that it would probably take 15 to 20 years to restore the damaged riverbanks as well as the fish species that perished from this incident.”

Weber will be submitting parliamentary questions on why nothing seemed to have been done to rehabilitate the mine, and what steps would be taken to prevent similar disasters.

Similar concerns were raised in Kerry Bobbins’ report seven years ago, when she suggested that the South African mining sector had a legacy of externalising the costs of its social and environmental impacts.

“Though the mining industry has made a significant contribution to the economic development of (Gauteng) and South Africa more generally, mines often used irresponsible mining methods with little regard for society and the environment.

“Short- and long-term environmental costs associated with mining have historically been deflected from the balance sheets of mining companies. These environmental remediation costs, not counted as part of mines’ direct production expenses, have compounded over time, and typically peak after mines have closed and become derelict and ownerless.”

In light of the sheer number of ownerless and derelict mines in South Africa, efforts made by the government to rehabilitate mines had been slow. For example, while six mines were allocated funds during 2011/12 for rehabilitation, only three were successfully rehabilitated. This increased to 13 rehabilitated mines in 2012/13 and 28 in 2013/14.

Bobbins also pointed to the increased risk of vital water storage dams being sterilised by mine-borne poisons if the problem of AMD was not taken seriously. One example was the Robinson Dam on the West Rand.

“Robinson Dam is part of the Wonderfontein catchment which has been heavily polluted with metals such as uranium. The water in Robinson Dam is said to have deteriorated after a mine began pumping acid water into the dam as an emergency measure in response to (AMD) decant in 2002.”

As a result, water in Robinson Dam was believed to have a pH as low as 2.2, while dissolved uranium had also created a radioactive environment that could not support any life forms.

“The occurrence of sterile water bodies such as the Robinson Dam are the clearest warning of what may result if more care is not taken to prevent the destruction of natural ecosystems and contamination of potable water by mining-related waste.

“As the guardian and regulator of mining, the government has accrued, as property of the state, over 6,000 ownerless and derelict mines. The financial liabilities of these mines — notably the direct costs of their remediation — therefore now sit as a tax burden on the broader economy.