The herd of elephants moves silently through the human-dominated landscape, opting for the secrecy afforded by nocturnal passage. In fact, they are so affected by human farming activities that they will not pass this way during the daylight hours. This is according to a new study comparing elephant activity times and the use of wildlife corridors depending on the type of human development surrounding them.

Giraffes May Be as Socially Complex as Chimps and Elephants

Giraffes May Be as Socially Complex as Chimps and Elephants

The research conducted by Elephants Without Borders used data from 2012 to 2019 to investigate the impact of human pressures on elephants. The study compares six wildlife corridors in the Chobe District in northern Botswana in two vastly different human-dominated landscapes. The first was the townships of Kasane and Kazungula, while the second was the farming villages of the Chobe Enclave along the Chobe River floodplain.

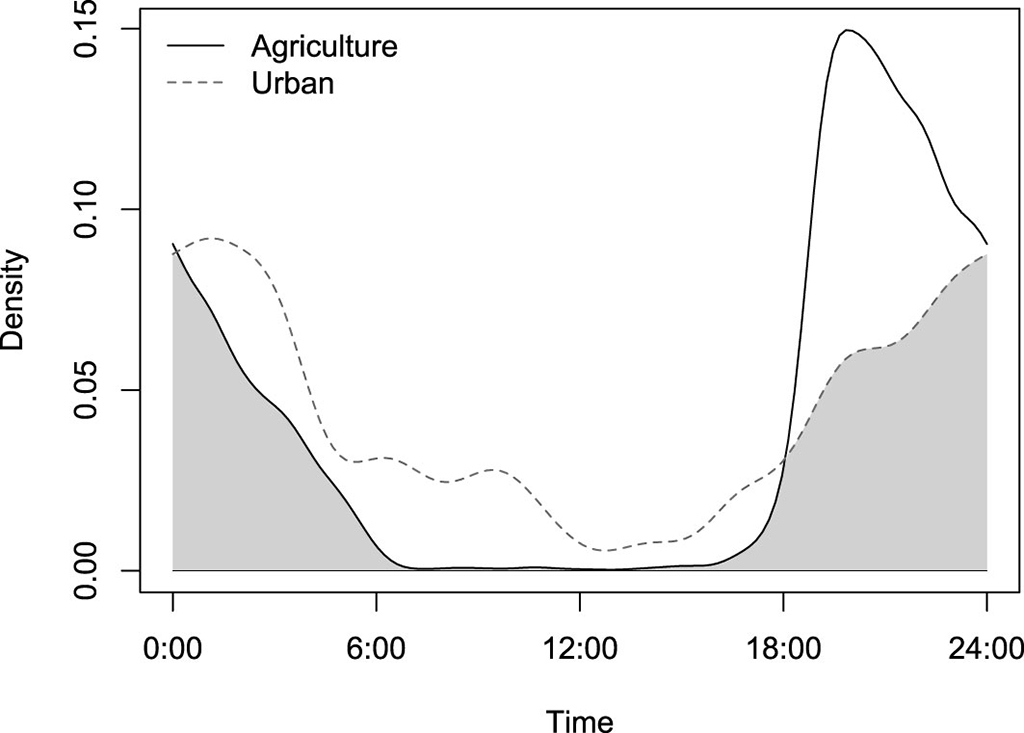

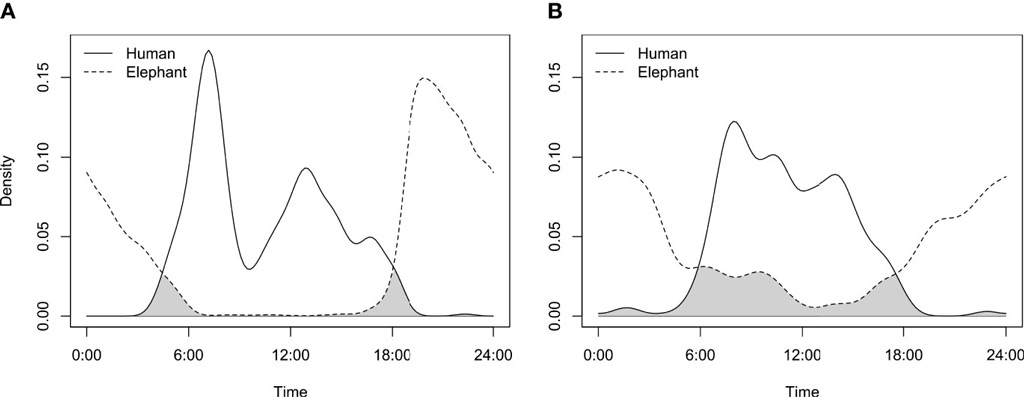

Using motion-triggered cameras, scientists found that elephants moved through the wildlife corridors in agricultural landscapes almost exclusively at night, between the hours of 18:00 and 06:00. Their use periods overlapped with those of humans by just 9.1% and were not affected by crop season (suggesting that crop raiding was not the motivation). By contrast, those travelling through the urban areas were less obviously selective about their activity timings, overlapping with those of humans by 26.8%.

This research is consistent with previous research indicating that elephants change their activity patterns to reduce the risk of human encounters in a human-dominated landscape. However, the urban-activity patterns of this new research stand out. As lead author Dr Tempe Adams explains, these findings are remarkable because they show that elephants appear to distinguish different types of human developments associated with diverse risk levels and adjust their behaviours accordingly.

Research such as this becomes important as increasing human development creates more isolated islands of ever-shrinking wild habitats. Wildlife corridors connecting these remaining wilderness areas are now an essential management tool in conserving many iconic species. These corridors allow access to seasonal resources, dispersal (and associated genetic diversity) and increased resilience to changing environmental conditions. However, planning future corridors and ensuring their maintenance cannot take place without a comprehensive understanding of how different land uses and human pressures (and seasonal variations) impact how and when wild animals use these corridors.

As this research shows, the elephants of Chobe appear to have learnt how to assess human risk and mitigate their chances of an antagonistic encounter with humans. Their activity patterns differ based on surrounding human land-use on an hourly and daily basis.