According to a survey by industry body Make UK, 29 per cent of manufacturing vacancies were considered hard to fill by employers in 2018, a small improvement on the 30 per cent reported in 2015 and 2013. Add in the UK’s ongoing shortage of engineers and a rapidly ageing workforce, and it becomes increasingly hard for leaders in manufacturing to know where to start when it comes to talent planning.

“Engineering businesses have always required a unique combination of technical and soft leadership skills, and it remains in short supply,” says Carol Burke, managing director at Unipart Manufacturing Group.

“The fourth industrial revolution is affecting all aspects of business because process is no longer about machines and people, but now about data. It is crucial that our employees have the imagination and creativity to realise the full potential of digitilisation and end-to-end integration.”

Finding the right balance between the skills new technology requires and upskilling existing talent pools is the key challenge

Creating a stronger manufacturing talent pipeline

To facilitate this growing demand, Unipart co-founded the Institute for Advanced Manufacturing and Engineering (AME) with Coventry University in 2014, with the aim of solving three key challenges for the business: solving skills shortages in manufacturing and engineering; increasing its capacity to fund research and development; and improving commercial benefits to its customers.

The institute houses state-of-the-art machinery and provides students with access to Unipart’s operations, giving them a “live” environment in which to test their skills. Its first cohort of students graduated in 2018, with all either entering industry or going into postgraduate research.

“Our new talent pipeline is a mixture of AME graduates and apprentices. We want agile, flexible, creative and entrepreneurial employees, and this is vital in the digital world,” says Ms Burke.

For others in the industry, finding the right balance between the skills new technology requires and upskilling existing talent pools is the key challenge.

Siemens went through a period of structural reorganisation in 2014 to prepare it for the challenges facing the manufacturing industry, with industrial digitalisation being a key component of its Vision 2020 strategy. Commenting on the reasoning behind the changes in 2018, Siemens president and chief executive Joe Kaeser called digitilisation “the greatest transformation in the history of industry”.

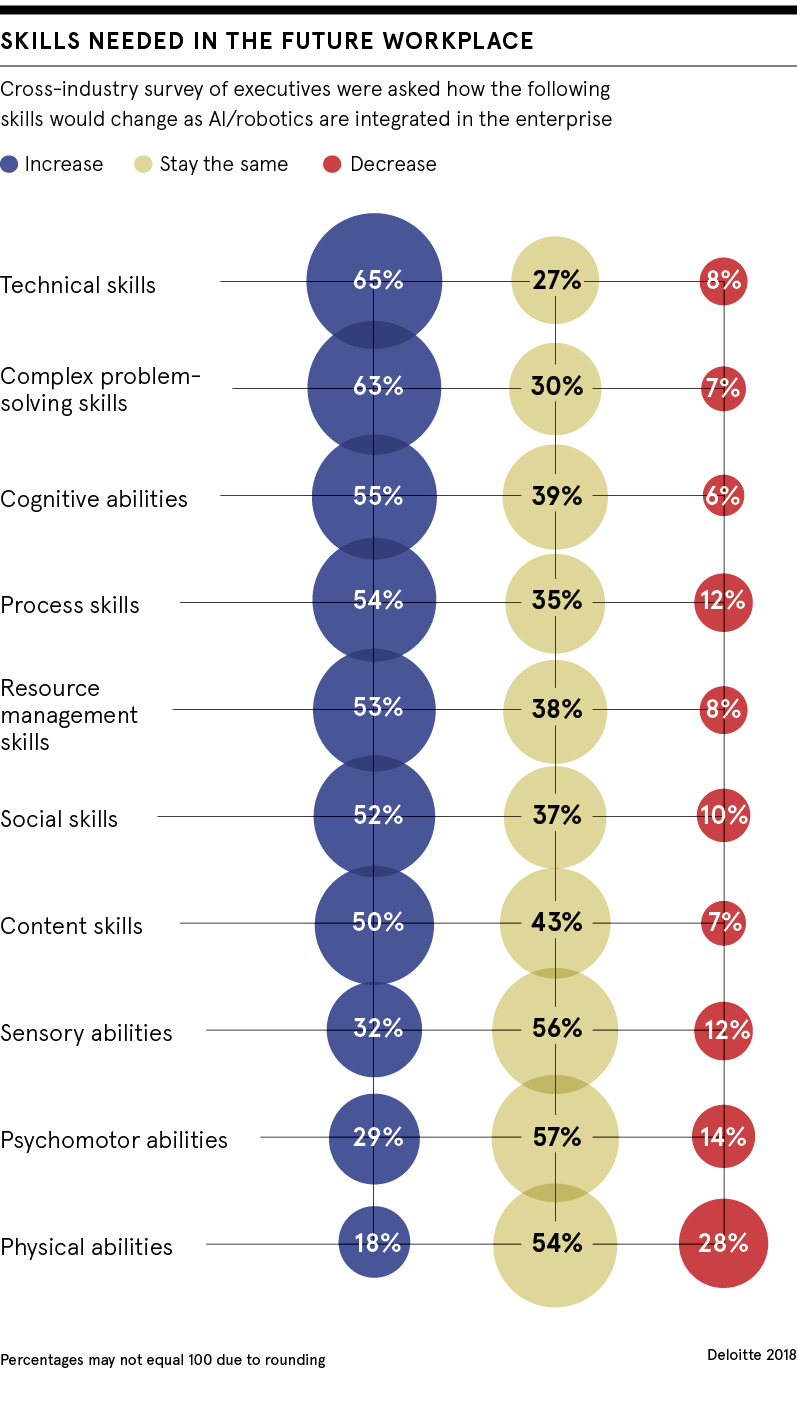

Brian Holliday, managing director of Siemens’ Digital Factory, the German manufacturer’s data integration wing, says: “From a talent perspective, many new roles are emerging in app development, connectivity and software engineering. Technology won’t replace people in future factories, but it will augment human effort through artificial intelligence and ‘co-bots’ [robots that work alongside people on the shop floor], so finding the right balance will be crucial to our survival.

“We won’t build factories in the future without full digital simulation and we will be increasingly reliant on data for decisions. Our engineers and managers will need to continuously develop new capabilities and embrace new tools.”

Like Unipart, Siemens is hoping to create industry-ready graduates by partnering with universities on research and qualifications. It has seven partner universities in the UK, including the universities of Cambridge, Manchester and Lincoln. The latter houses its newly opened Digital Mindsphere Lab, which is a hub for developing its cloud-based operating service Mindsphere.

However, as with many industrial companies, Siemens’ workforce largely consists of mature engineering talent, and apprentices and graduates, with a significant gap in the middle, says Mr Holliday.

Dealing with this manufacturing talent gap is a major headache for an industry already struggling to meet demand. According to the Make UK, two fifths of manufacturers say 40 per cent of their workforce is above the age of 50. The looming Brexit deadline cannot be ignored either, with European Union nationals making up 11 per cent of the average manufacturer’s workforce and proper guidance on post-Brexit rules still to be decided.

For Rockwell Automation’s UK director Mark Bottomley, Brexit isn’t manufacturing’s defining issue for coming years, but rather the industry’s ability to adopt technology in the fourth industrial revolution. He believes this is what will govern future success and talent strategies are key to fostering this change.

“The single most exciting thing about the fourth industrial revolution is the breadth of manufacturing talent that can find expression, the breadth of skills that can be developed and where these attributes are taking the industry. There are barriers to overcome, but the biggest risk comes in not embracing the challenge,” says Mr Bottomley.

A 2017 IDC FutureScape report into global manufacturing trends supports this view, predicting that 60 per cent of the largest 2,000 manufacturers will be reliant on digital platforms for processes by 2020 and 80 per cent of human-to-machine interactions using immersive interfaces such as augmented reality by 2030.

To meet this, Mr Bottomley recommends a two-pronged approach to manufacturing talent planning with inward and outward strategies.

“Investing in the people you have is hugely important. Your people already understand what you do, but do you really understand what they could do if given the right opportunities? Offering your people the chance to learn and further their own careers also makes you more appealing to other skilled talent you’ll need to recruit,” he says.

“The other half of the equation is about looking into the future and outside your company to understand the skills you’ll need down the line. Some of these skills can be redeployed through the use of automation technologies to free up existing workforces, but industry in general still needs an influx of engineers for the future.”

Perhaps this is the crux of the issue. While digitalisation is certainly the future of manufacturing, in talent terms the present is still a challenge. According to Make UK, the sector needs to find 124,000 new employees with level 3 and above engineering skills each year, but faces a deficit of 54,000 annually. More government help is required as programmes like the Apprenticeship Levy and National Retraining Scheme are yet to have the desired impact. Until manufacturers can close this numbers gap, workforce planning will remain a significant challenge.