The outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) from April 2023, including the difficult-to-control H7N6 strain, has led to the culling of more than 7.5 million birds, resulting in egg shortages on supermarket shelves.

In a presentation to Parliament, the South African Poultry Association’s general manager of egg organisation, Dr Abongile Balarane, noted that it “will take 17 months before the local sector recovers from its lost production”. Sustained shortages of poultry products pose a grave threat to South African consumers, with the prospect of rapidly increasing consumer prices.

In response, Trade, Industry and Competition Minister Ebrahim Patel directed that the International Trade Administration Commission (Itac) conduct an expedited investigation to consider a temporary rebate on customs and anti-dumping duties on chicken imports. The deadline for comments and countercomments from stakeholders has passed, with Itac now conducting the investigation.

There are many reasons that Itac and the minister need to seriously consider a temporary reduction of duties. A key reason is that the recommendation is pro-poor. In the face of high unemployment and food price increases that have exceeded wage increases, South African households are increasingly vulnerable to food insecurity.

Poor households are most severely affected because they lack access to job opportunities and depend primarily on social grants and other transfers to sustain themselves. In a recent study, Shoprite estimated that one in five South African households don’t know where their next meal will come from.

Chicken is a primary source of protein for households, particularly poor ones. According to the South African 2015 Living Conditions Survey, poor households (the poorest 40% by expenditure per capita) spend 13% of their food expenditure and 64% of meat expenditure on chicken. In contrast, the wealthiest 10% of households only spend 7% of their food expenditure and 28% of their meat expenditure on chicken products. Poor households are therefore particularly vulnerable to chicken price increases.

Chicken price increases have disproportionately contributed to food price inflation over the past few years, with the strongest price increases in individual quick frozen bone-in chicken portions. Frozen bone-in cuts such as wings, drumsticks, thighs and leg quarters are mostly eaten by poor households.

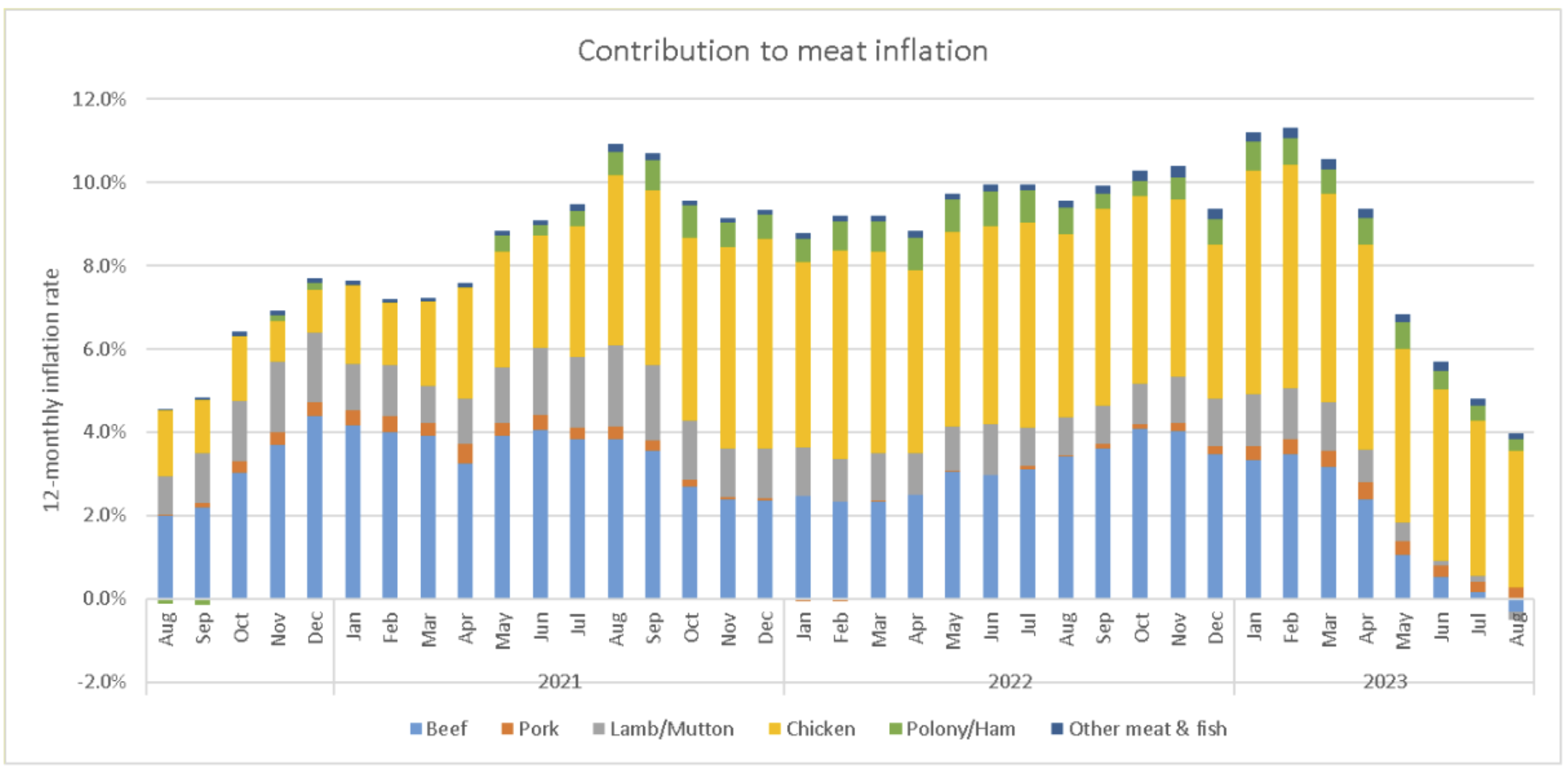

From 2020, consumer prices of meat products rose rapidly, averaging close to 10% on an annualised basis from August 2021 to March 2023. Annualised increases in the price of individual quick frozen chicken were higher, averaging 13% over this period. Annual meat inflation subsequently fell, reaching 3.3% in August 2023, but the decline can almost entirely be attributed to declining inflation of other meat products, particularly beef and lamb/mutton.

Chicken price inflation remained stubbornly high, falling to only 7.4% in August. Chicken price increases are therefore an important contributor to the increased food vulnerability of poor households.

Own calculations using consumer price data (Graph: Statistics South Africa)

A multitude of high and rising barriers to imports of chicken products lies behind the strong increase in the consumer price of chicken products. These tariff increases have also been regressive, affecting chicken products consumed by poor households the most.

The general tariff on chicken imports was raised in October 2013 and again in March 2020. Import tariffs on frozen bone-in cuts, which account for more than 40% of total import volumes, rose from 220c/kg or 18% ad valorem equivalent to 37% in 2013, and then to 62% in 2020.

Tariffs also increased on frozen whole chicken (27% to 82% in 2013), boneless cuts (5% to 12% in 2013 and then 42% in 2020), carcasses (27% to 31% in 2013) and offal (27% to 30% in 2013). Tariffs on fresh chicken (whole or cuts) and frozen mechanically deboned meat remained at 0%.

Our estimates indicate that for every 10% increase in the aggregate import price from duties, there is a 4.8% increase in the consumer price of frozen chicken.

The increases in the general tariff do not apply to imports from the European Union (EU), with which South Africa has a free trade agreement. This resulted in a shift in imports away from cheaper sources such as Brazil, towards more expensive varieties from the EU.

However, the import tariff increases were followed by a series of additional restrictions targeting imports, particularly of frozen bone-in cuts, from the EU. These include anti-dumping duties on England, the Netherlands and Germany from July 2014, special safeguard duties on imports of frozen bone-in portions from the European Union from 28 September 2018 to March 2022, and a sequence of import bans on chicken products from different European countries from November 2016 in response to outbreaks of avian influenza in Europe.

By the beginning of 2023, for example, no imports from European countries were permitted. Most recently, in August 2023, after a 12-month delay, anti-dumping duties ranging between 2% and 265% were imposed on imports of frozen bone-in cuts from Brazil, Denmark, Ireland, Poland and Spain.

The imposition of avian flu bans and anti-dumping measures are necessary to protect consumers from harmful infection and the domestic industry from unfair competition. The net effect, however, of the compounding set of import restrictions is a much less competitive domestic market that is susceptible to large price increases in the face of domestic supply shortages following the HPAI outbreak.

Import volumes of frozen bone-in and boneless chicken are now a third of what they were in 2018 and at levels last seen in 2010. The number of foreign sources of frozen chicken imports fell from 21 in 2018 to 11 during the first five months of 2023. Import volumes of mechanically deboned meat have remained high, but given no domestic production of mechanically deboned meat, these imports pose no threat to the domestic poultry industry.

The tightening of the import market has had the effect of raising the price of frozen chicken products imported into the country. The South African Poultry Association argues that foreign exporters absorb the tariff increases through lower prices, thus insulating domestic consumers from price increases. However, a closer look at the data indicates that while this may occur at the margin, it is not the case on aggregate.

As import duties and restrictions have been imposed, the gap between the import price inclusive and exclusive of all duties has risen. In 2012, import duties collected on frozen bone-in and boneless imports were only 4% of the value of imports. There was little change in 2013/14, despite the raising of import tariffs, as imports shifted from dutiable (such as Brazil) to non-dutiable EU sources.

But from 2016 average duties collected started to rise sharply in response to the anti-dumping measures imposed on the Netherlands, Germany and the UK, the safeguards imposed on EU imports and the avian influenza import bans on the Netherlands and other EU countries from 2017.

Duties collected rose even further from 2020 as imports from the EU were further constrained by a renewed outbreak of avian flu. By 2022, access to non-dutiable imports had effectively been closed off, resulting in a duty-inclusive import price that was 60% higher than the foreign export price. The implication has been a sharp increase in the landed cost of imported frozen chicken pieces.

Calculations using South African Revenue Services data. The figure covers frozen bone-in and boneless cuts. Import prices are measured at free-on-board prices.

Restricted access to imports and the increase in the duty-inclusive price of imports are key factors behind the relatively strong increases in the consumer price of chicken products. The South African Poultry Association argues that lower import tariffs will not benefit consumers, since the importers merely increase their profit margins and don’t pass on the lower prices to consumers.

However, the evidence does not support this argument. During the last severe avian influenza outbreak in South Africa in 2017/18, the consumer price of frozen chicken rose sharply. In a 2022 South African Reserve Bank working paper, The consumer price effects of specific trade policy restrictions in South Africa, we find strong evidence that consumer prices rise significantly in response to higher import duties. Consumer prices do not increase by the full tariff increase, as transport costs and wholesale and retail margins make up a large share of the overall consumer price.

Nevertheless, our estimates indicate that for every 10% increase in the aggregate import price from duties, there is a 4.8% increase in the consumer price of frozen chicken. These results imply that the combination of tariff and anti-dumping measures from 2012 to 2022 have raised consumer prices of frozen chicken by an estimated 21%.

This outcome makes logical economic sense. Tariff policy inherently involves trade-offs. By protecting the domestic industry from import competition, domestic producers are able to raise their prices, profitability and viability. The trade-off is that the tariffs impose higher costs on consumers. The challenge in the case of poultry is that the consumers are disproportionately poor, whereas the producers are concentrated in few firms.

Solutions

The government faces several options to ameliorate the potential negative impact of the avian influenza crisis on South African consumers.

First, a temporary rebate on the general tariff should be granted, at least to the rates that applied before March 2020. The temporary removal of customs duties will not negatively affect the short- or long-run competitiveness of the domestic chicken industry. Access to poultry products from major exporters to South Africa remain constrained by avian flu bans and anti-dumping measures, and the remaining tariffs (such as 32% for frozen bone-in cuts) will still confer significant levels of protection to the domestic firms. Even with the rebate, demand for domestic chicken will exceed domestic supply, and will therefore have no impact on the sales of domestic products. The rebate, however, will provide some relief to consumers who have faced very high food inflation.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Poultry producers bear crippling cost of avian flu as government accused of dragging its feet

Second, as argued by the Association of Meat Importers and Exporters, the government can be pro-active in reinstating import permits for countries that had been declared free of bird flu. These imports pose no threat to domestic consumers, and continued restriction has the effect of reducing access to alternative food supplies, thus increasing our vulnerability to global and national supply shocks.

Third, the government should not zero-rate value added tax (VAT) on poultry products without undertaking much more research on its impact. Zero-rating VAT on poultry has the potential to benefit poor households, but this depends crucially on whether the VAT reductions are passed on to consumers. The zero-rating of VAT will also have the unintended consequence of benefiting wealthy households who account for a high share of overall chicken consumption. VAT tax receipts for the government will also fall, placing an additional burden on the state in a tight fiscal environment. Targeted interventions including the supply of food coupons and food packages to poor households may be a better option to consider.

Professor Lawrence Edwards is the director, and Jing Chien the research coordinator at Policy Research in International Services and Manufacturing, a research and policy unit in the School of Economics, University of Cape Town.